In the Trump era, a small slice of Republican elites has commanded an enormous share of political coverage. Those Republican officials have found themselves caught between their personal revulsion for Trump and their professional incentive to placate the barbaric champion selected by their party’s voters.

The obsessive attention paid to those Republican elites is fully warranted. As Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky’s How Democracies Die found, the key variable determining whether a democracy can fight off an authoritarian challenge is whether the aspiring dictator’s coalitional allies stay with him and exploit the fruits of power or defeat him to form a pro-democracy coalition with their ideological adversaries. As we now know, they have overwhelmingly placed their bets with Trump and the movement he has built, which refuses to acknowledge the legitimacy of Democratic political success in any form.

The mental processes of these Republicans have hardly been obscured. They have leaked relentlessly to the media, explaining both their contempt for their party’s golfer-warlord and their conviction that they must continue to serve his interests, at least in public. Trump’s reluctant allies have supplied a stream of details that damn both him and themselves (among the latter is the now-notorious Republican staffer who said, “What is the downside for humoring him for this little bit of time?,” as a justification to support Trump’s refusal to concede defeat to Joe Biden).

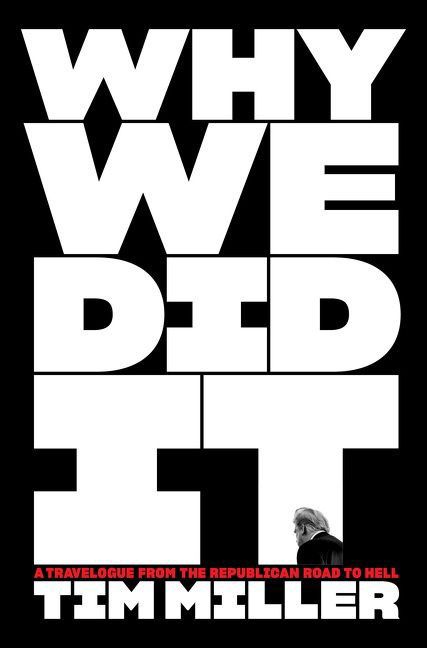

Tim Miller’s superb new book, Why We Did It, examines the mind-set of these cross-pressured Republican elites. Miller is one of the relatively small number of Republicans who broke completely with the party. Yet his ties to its network of elected officials and advisers are broad enough to give him unique insight into the thinking of those who didn’t join him on the other side.

Miller’s book takes the form of a series of psychological profiles of Republican officials responding to Trump, beginning with himself. Miller came up through the ranks of mainstream Republican hackery, attaching himself to generally respectable figures (Jon Huntsman, Jeb Bush) and party organs. Despite his initial contempt for Trump, it took a couple years for Miller to summon the clarity to break fully with the party. This process of internal wrestling gives Miller an inside perspective of the pressures bearing down on his little tribe.

After concluding his self-examination, Miller turns his lens onto several of his colleagues whose breaks with Trump took longer, or, in some cases, did not occur at all. He finds a subtle blend of rationalizations. And while the specifics of every Trump-supporting Republican differ, one motif of his subjects is a failure to summon the imagination and moral courage to break free from their career path and social identity. By the time you have attained a job in Republican politics that carries enough influence to matter, you have enough at stake professionally and socially that truly abandoning the party becomes as difficult to imagine as a fish leaving the water for land.

As an outsider, it has been astonishing to watch a series of Republican outsiders who seem to believe that the highest theoretical level of rebellion they can register is to leak anonymous professions of concern while publicly remaining onside. Miller does not justify that mentality — to the contrary, he makes his disgust perfectly clear — yet still manages to show why so many people have it.

Perhaps the most surprising factor Miller identifies in his subjects, very much including himself, is their profound cynicism. One would expect any seasoned political operative to exhibit some level of detachment from their field given that the work inevitably requires sanding down complex truths into slogans and taglines. But Miller reveals that he and his colleagues considered the whole enterprise fundamentally bullshit. Nearly to a person, they thought of politics as a game, and they considered the absence of ethics a mark of sophistication.

Miller aptly shows how the pervasive cynicism among his party’s political class naturally produced the conditions for its capitulation to Trump. A different question, and one that lies outside Miller’s scope of analysis, is, What produced that cynicism in the first place? (This is not a criticism of the book; no book can answer every question, and Why We Did It very persuasively answers the questions it sets out to resolve.)

You can find hints of an answer in Miller’s recollection of his participation in a commission formed by the Republican Party after the 2012 election. Known unofficially as the “autopsy,” the party called for moderation on social issues, especially immigration, in order to attract more minorities.

Miller frankly acknowledges that, even though Barack Obama relentlessly hammered its candidate as a heartless plutocrat bent on cutting taxes for the wealthy, the party never even considered the possibility that its economic agenda had any role in its defeat. “The notion that we should consider advocating for trashing the economic and foreign-policy parts of the GOP’s three-legged stool was so verboten,” he writes, “as to never even have come up during the autopsy’s internal discussions.” It’s not just that Republicans rejected the hypothesis that Paul Ryan’s program was a drag on the ticket; they refused to entertain the notion at all.

The reason for this, which Miller touches on briefly, is that the Republican Party considers its basic agenda of low taxes for the rich and business-friendly regulation to be its core policy objective. Of course, almost any political party has core objectives that are at least somewhat at odds with public opinion, and the Democrats are certainly not immune. But it seems plausible that the Republican Party’s institutional practice of manufacturing pseudo-issues to gin up the base is built on an assumption that its base does not actually care about the party’s central policy goals. That cavernous gap between the means of campaigning and the ends of governing produced a political class of cynics and nihilists.

Miller isn’t responsible for enumerating the causes of Trumpism. He has tasked himself with explaining how the slice of Republican officials had the greatest chance to stand up to a madman and, for the most part, sloughed off its duty.

One doesn’t need to see these Republicans as monsters to grasp their untrustworthiness. Miller presents them as achingly human. It is their humanness that renders them so terrifyingly weak and vulnerable in the face of evil. The only thing standing between the Republican Party and a second death blow is a soft pink wall of timorous apparatchiks. Miller’s tell-all should make us far more afraid.