New York University recently fired a professor after students complained that his class was too hard.

The instructor, 84-year-old Maitland Jones Jr., is a legend in his field who literally wrote the book on organic chemistry. The students are pandemic-rattled zoomers who, in a petition to the university, complained that Jones did not provide opportunities for extra credit and gave out grades in his orgo class that were “not an accurate reflection of the time and effort” that they had put into it. The university responded by (1) granting the students the opportunity to retroactively withdraw from the class and thus spare their transcripts from the smear of a low grade, and (2) abruptly terminating Jones’s teaching contract right before the start of fall semester.

The New York Times brought this saga to the world’s attention on Monday. The story proved to be a bit of a Rorschach test. Most everyone who read it saw it as a testament to some social ill. But precisely which cultural crisis one glimpsed depended on one’s preexisting concerns.

Some saw the story as a damning indictment of the media that would deem it national news. In their account, in this moment of ascendant fascism, European land battles, and economic chaos, it is shameful for major newspapers to keep making room for minor controversies on elite college campuses. This complaint is fair enough in the abstract. But I think it’s misguided for two reasons.

First, in my view, gripes about overcoverage of campus contretemps misunderstand the news media’s nature and purpose. It is doubtlessly true that, were news organizations to set coverage priorities according to an exacting utilitarian calculus of objective importance, NYU laying off an octogenarian with the worst student evaluations in his department would not make the cut. But that isn’t how the news works. Newspapers do have a civic responsibility to inform. But they also have a fiduciary responsibility to entertain. And in any case, they can’t really serve their civic function if they don’t cater to their readers’ sensibilities somewhat. There are a great many stories of tremendous humanitarian importance that the median procrastinating American laptop worker simply is not interested in reading. The New York Times should probably cover the Ethiopian civil war and South Asian water crisis more than it has. But to give such events billing proportionate to their objective importance would require zeroing out coverage of tons of relatively trivial issues that are nonetheless more engaging for the paper’s core constituency.

“People who read about current affairs avidly, on a daily basis” is a relatively insular, predominately college-educated community that spends a lot of its waking hours online and/or in the worlds of media and academia. For people like us, cultural trends within the professional class in general, and on campus in particular, are tantamount to “local issues”; they’re about what’s happening in our extended social sphere. So we’re generally more interested in arguing about whether college kids are entitled and censorious than about Sri Lanka’s economic crisis. Which means we’re more likely to click on and share stories about the former than ones about the latter. And those who hate-read “campus drama” stories and quote tweet them only to express their frustration that people are reading and sharing such stories are very much implicated in the phenomenon they bemoan.

Not that there’s anything wrong with criticizing the way these stories are written and framed! It’s perfectly legitimate to care about how the cultural trends in one’s milieu are characterized or misrepresented. But that concern is itself reflective of why the general subject of campus controversies constitutes national news from the standpoint of the New York Times.

More concretely, though, the notion that the Times’s story wasn’t worth reporting seems off-base because this little drama really does speak to several important developments in American life. It is possible that the tenor and balance of the Times’s reporting did not do justice to the students’ complaints. It’s not exactly hard to believe that an 84-year-old might not be the most engaging and accessible instructor for students who were born in 2004. Nevertheless, the story is illustrative of the burgeoning consumer-centric model of the university and its pathologies. Whatever the broader merits of the students’ complaints, their suggestion that grades should accurately reflect “the time and effort” put into the class, irrespective of whether that time and effort translated into subject mastery, does seem to bespeak the entitlement of a consumer more than the humility of the ideal pupil. In any case, the university certainly responded by treating the students less as prospective scholars than as “always right” customers. In an email to Jones explaining why the university decided to let students retroactively withdraw from the class that they had failed, the NYU chemistry department’s director of undergraduate studies wrote that the plan would “extend a gentle but firm hand to the students and those who pay the tuition bills.”

To be fair, treating students as entitled consumers makes perfect sense when they’re shelling out $55,000-plus a year to attend your university (especially when they’re paying that sum to attend it via Zoom, as many students did during the worst of the pandemic). But the consumer model is nevertheless corrosive of academic standards and thus, potentially, of the quality of the education that students are taking on debt to receive (what 18-year-olds want from school, and what they need from it, will not always and everywhere be the same). And it is antithetical to academic freedom in a context where a growing share of university instructors are untenured adjuncts, working on year-to-year contracts. An 84-year-old being forced into retirement is no great tragedy. But to the extent that the precedent set by Jones’s firing intimidates other adjuncts into seeking the best possible student evaluations — even if that means refusing to challenge students much academically or intellectually — the core functions of the university are degraded. And indeed, one chemistry professor at NYU told the Times, “Now the faculty who are not tenured are looking at this case and thinking, Wow, what if this happens to me and they don’t renew my contract?

Primary responsibility for this state of affairs scarcely lies with the students. They did not ask NYU to fire Jones. Nor did they engineer America’s grotesque system of university financing or the hyperexploitative academic job market. But the story of Jones’s firing nevertheless reflects those real problems.

It also speaks to the genuine crisis of COVID learning loss. Testimonials from both students and instructors interviewed for the piece indicate that the pandemic undermined the quality of an entire cohort’s education, and thus, of its academic development. Those anecdotes comport with a growing body of social-science research demonstrating that COVID and its associated restrictions lowered students’ test scores. Ideally, many millions of students would be held back to repeat the year that they effectively lost to substandard schooling. But of course, at universities that charge more than the U.S. median income for a year of instruction, this is not typically viable.

But there is another, less appreciated dimension to the NYU affair: the genuinely excessive difficulty of becoming a doctor in the United States.

The primary reason why students found their failure to pass Jones’s class so devastating was that organic chemistry is a “weed out” class for would-be doctors. Every year, “orgo” thins the ranks of the nation’s premeds, with those unable to master the famously difficult course forfeiting their dreams of practicing medicine. But it is not clear that this filtering process is actually in the public interest.

The substance of the organic-chemistry curriculum does not come up all that much in medical training or practice. There are myriad fields of medicine where an inability to command the finer points of the subject would have no negative impact on the quality of care. As the former dean of Harvard Medical School Jeffrey Flier argued Monday, an undergraduate can do poorly in orgo and nevertheless make a “great doc.”

If a mastery of organic chemistry’s subject matter is not absolutely necessary to practice medicine, why have we made that a precondition for medical training in the United States? One answer is that we need some arbitrary mechanism for filtering aspiring doctors into other professions because we manufactured a scarcity of medical school and residency slots.

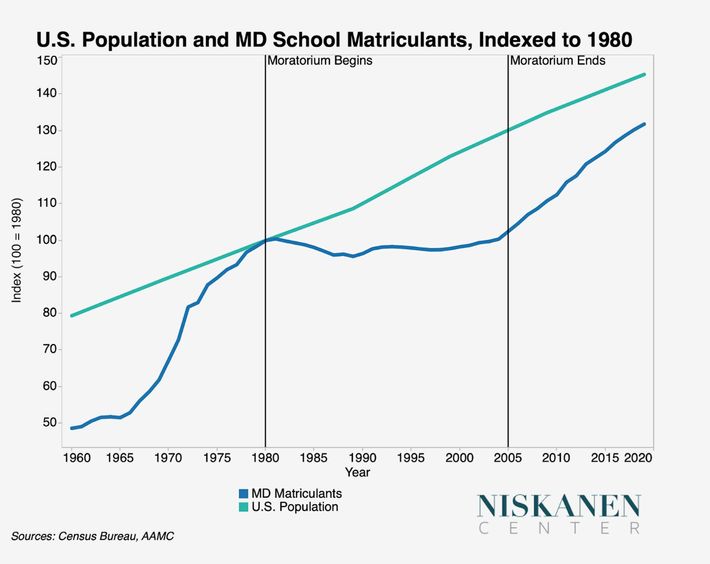

As Robert Orr of the Niskanen Center explains, the U.S. government issued a report in 1981 warning of an imminent “physician surplus” and recommending “immediate action to curtail both the domestic training of physicians as well as the admittance of those trained outside of the country.” The report’s argument was ill conceived. Its authors did not recognize that demand for health care is not static, but rather invariably rises as nations get wealthier. There is no hard limit on the human desire for health and longevity. If we can afford to pay for more services that ostensibly improve our physical well-being or reduce our risk of near-term mortality, we’re going to do so. Thus, rather than encouraging Americans to spend less on health care, restricting the supply of doctors was only ever going to change what we spent out health-care dollars on. Instead of giving the American public easy access to abundant providers, the U.S. health-care system directed us towards high-intensity medical interventions. This system delivered some beneficent innovations but also a strong tendency toward financially motivated overtreatment that poorly served patients and wasted resources.

If the government’s report poorly diagnosed the healthcare system’s ills, its prescriptions were nevertheless convenient for incumbent doctors. After all, the fewer people practicing medicine in the U.S., the stronger the bargaining power of those who do. Partly as a result of such entrenched interests, the report’s recommendations were largely followed. Federal support for medical-school scholarships was scaled back; residency training requirements were scaled up; federal support for residencies was gradually drawn down; and medical schools honored a voluntary moratorium on establishing new schools.

As a result, the United States now has fewer practicing physicians per capita than virtually any other developed country. In the Commonwealth Fund’s analysis of health-care accessibility in 12 wealthy nations, the U.S. came in dead last. It is now widely recognized that America has never suffered from a physician surplus but only from a persistent shortage. The Association of American Medical Colleges projects that the U.S. will have between 43,000 and 121,000 fewer physicians than needed by 2030.

On the other hand, American doctors enjoy salaries more than 50 percent higher than their peers in other rich countries. But that does not seem like an optimal tradeoff, at least for anyone who’s not a doctor.

The exceptional difficulty of organic chemistry — and its ubiquity as a premed requirement — is not the primary bottleneck holding up America’s physician supply. But it is a tool for managing and sustaining that bottleneck. Decades of underinvestment led to fewer medical-school slots than aspiring doctors. Instead of maximizing the number of competent physicians in the U.S. by providing more flexible and relevant standards for medical-school admission, we’ve decided to use “weed out” classes to perpetuate a system that leaves us with too few doctors and directs too many talented young people into less socially beneficial professions.

All of which is to say: We’re never going to stop the news media from covering the campus controversies whose newsworthiness we love to argue about. But we can and should nudge public debate over these stories toward the most important issues that inform them. I don’t know whether professor Jones’s class was excessively difficult. But I’m pretty sure that, in America, it is too easy for a professor to get fired, and too hard for a smart young person to become a doctor.