Joe Biden looked out at about 100 big-spending supporters gathered in a donor’s home just two blocks north of Trump Tower last month and insisted there was still plenty he wanted to do with his presidency. “Folks, I just think there’s enormous opportunities. Enormous opportunities!” he told the chummy crowd, which included Robert De Niro and Eric Adams. He was raising cash for the Democratic National Committee, the party’s hub and the organization expected to house the early infrastructure of his reelection campaign after November. “But this isn’t about 2024,” he said. “This is about 2022. Twenty twenty-two!”

It was about both.

It wasn’t long ago that even many of Biden’s allies saw an entirely different — and far grimmer — proposition reflected in the midterms. As recently as this summer, the president was fighting for his legacy and the ability to get something done in Congress over the next two years as part of his reelection strategy. Skepticism ran deep even within the Democratic Party that the 79-year-old would be running again, no matter what he said when he was asked about it. In this world, as the party worked to minimize losses in the House and hang on to the Senate and state-level races this fall, behind-the-scenes chatter would inevitably focus on who might emerge as the leading candidates to replace Biden after the elections. The midterms would be important for determining the trajectory of Biden’s presidency, but they might be just as important for setting the party’s direction as it evaluated his would-be replacements.

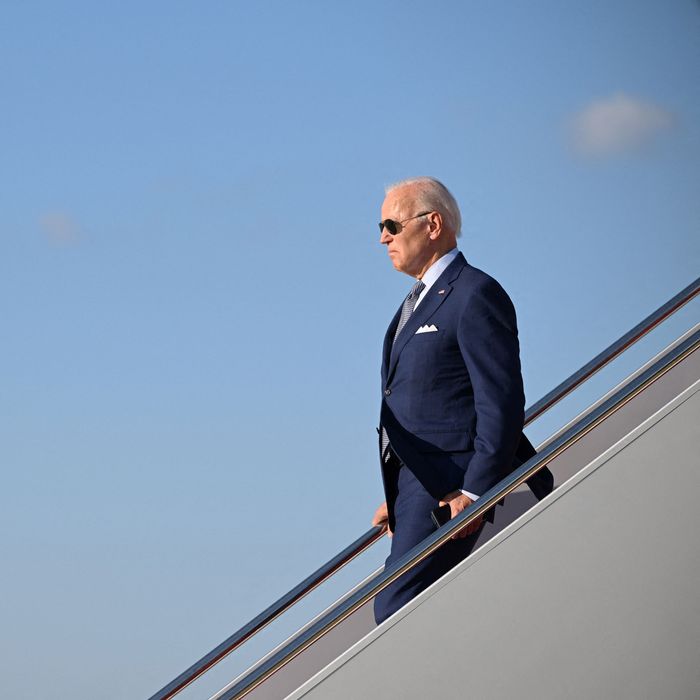

The view from early October — with gas prices in check, climate legislation passed, and Democrats feeling a bit less dire about next month’s votes and Biden’s overall performance — could hardly be less compatible with that line of thinking. With just weeks until Election Day, Biden and his political orbit are unmistakably approaching the home stretch as an operation gearing up for an increasingly likely reelection bid with the understanding that a successful midterm effort should be an important first step. They aren’t depending on an outright positive result for Democrats; they are realistic about what usually happens in a president’s first midterms, and they remember Barack Obama’s 2010 “shellacking” and subsequent 2012 victory too well to assume midterm results translate neatly to presidential elections. But to many of the people close to the president and plenty of those directing party strategy, the two elections are intricately entwined. A rematch with Donald Trump looks increasingly inevitable to the president and many of his close associates, and that possibility is heavily informing their approach to November.

That means they’ve ditched Biden’s preferred kind of old-school Washington, D.C., caution dictating that the White House publicly focus on only one cycle at a time. It’s a sign of their intent to signal that Biden’s reelection campaign is at least provisionally a go — a significant step considering the continuing flow of questions about his future. And it’s an unavoidable acknowledgment that a Trump return looms larger than ever (and that a non-Trump GOP nominee would certainly run on Trumpism, a Biden adviser noted). As one senior Democrat close to the White House and familiar with its thinking put it, each of the midterm races squarely in the president’s view has something in common: “They have enormous importance for 2024.”

It’s not just that. “He wants to get some wins, but it’s also about getting his own voice back, about the things he’s done,” said another longtime Biden political adviser. He is primarily concerned with winning as many races as possible this fall, but campaigning in important states will allow him “to start laying out the contrasts, lay out the theory of the case of his work” ahead of a possible 2024 rematch, the adviser said. And for Biden in particular, “it’s just good for him when he’s out there. He looks better when he’s out around people,” continued the adviser, and he views his appearances in battlegrounds as “his focus group” on how the country is feeling and how to think about his campaign in two years.

Biden allies — frustrated by questions about his true 2024 intentions that no one would ask of a younger president — have for months informally pointed to the DNC’s activity as evidence of his plans. Since March 2021, with significant direction from the Biden political operation, which is still led by many of the people who worked on his 2020 campaign, the committee has focused its midterm-season investments on eight states with prominent races that will almost certainly play starring roles two years later. In many of them, Trump-allied election deniers are running to take on roles that could hand them control of election procedures in 2024. Seven of them (Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) have Senate races that could help swing control of the chamber as well as other close contests at the House or statewide level, and the eighth (Michigan) has highly competitive races for governor, attorney general, and secretary of state.

Using the DNC in such a pointed manner in a midterm season — far more than Obama did, for one — has granted Biden and his aides significant connection to state-level political operations and intel. It has given them an opportunity to inject the matter of Biden’s own record into the races and to experiment with how Democrats discuss it. Biden is now likely to campaign far more forcefully on his accomplishments than Obama did in 2010, when his White House was reeling from the backlash to Obamacare and the rise of the tea party but when no one really doubted he would still run for reelection.

In recent weeks, Biden has been increasingly open about the 2024 implications for the midterms in conversations with aides, friends, and allies. He’s always maintained — as many presidents do — that he’ll campaign for candidates wherever he can help them and will stay away wherever his presence (and low approval rating) is less welcome. Yet as the landscape has shifted in his favor, he has also leaned back into his 2018-to-2020-era insistence that he can campaign in places where other Democrats are pessimistic. He has, for instance, tried twice now to rally in Florida, which many in his party have all but written off as a reddening state, even though it’s been central to presidential elections for decades and where Charlie Crist is running an uphill battle to oust Governor Ron DeSantis, Biden’s second-most-likely 2024 opponent. (The rallies were postponed first because of Biden’s COVID-19 diagnosis and then because of Hurricane Ian. He visited the state this week to survey the storm damage and appeared with DeSantis in a nonpartisan capacity but was still overheard telling the Fort Myers mayor, “No one fucks with a Biden,” just minutes after standing with the governor.)

Biden has been talking more in private about a set of high-priority races shaping the politics of swing states that will be central to his reelection. In recent money-raising events and casual conversations, he has decried Senator Rick Scott’s proposal to chop Social Security, made light of Republican Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s attempts to define his party’s agenda, and zeroed in on Senator Lindsey Graham’s 15-week abortion-ban proposal. But he has been particularly open about one pol he especially wants to get rid of, whose ouster would hand Democrats both Senate seats in his vital battleground: Wisconsin senator Ron Johnson, whom he describes as notably draconian and an emblem of the new, warped GOP. Unlike Scott, McCarthy, or Graham, Johnson is up for reelection in a close state, and Biden has taken to reminding anyone who’ll listen about him. “Along comes Johnson,” Biden said recently, disbelievingly, after decrying Scott’s plan to have Congress reauthorize Medicare and Social Security every five years. He was speaking to high-paying donors in D.C. who’d gathered to support gubernatorial races, but Biden still went in on the senator — a sign of his special disdain for him since these donors weren’t there to hear about his race. “And he’s saying, ‘No, not every five years, every year. Every year.’ But he also wants to include veterans’ benefits and a whole range of other issues. The point is this is a different breed of cat. This is not your father’s Republican Party.”

In other conversations, Biden has regularly asked about the senatorial and gubernatorial races in Pennsylvania — the state where he grew up and arguably the one that handed him the presidency. (In the words of a senior Democrat in his political orbit, “He cares about it a ton.”) The same goes for Georgia, the one that gave him a (slim) Senate majority, and he has also asked to be kept apprised of the campaigns of down-ballot candidates he campaigned for in 2018, many of whom were important endorsers of his 2020 campaign and are running again in bellwether suburbs.

Still, though the efforts to tie 2022 and 2024 are far more often implicit than stated outright, they have remained complicated in some cases because of Biden’s underwater ratings in a handful of important states. Take the posture of two political allies who appear wary of appearing with him. Although Crist, one of Biden’s first endorsers in the 2020 race, has seemed willing to campaign with him in Florida, the same isn’t true for Orlando-area representative Val Demings, who is now running to unseat Senator Marco Rubio after Biden considered her as a potential running mate two years ago. Similarly, Biden has announced no plans to headline rallies in Ohio, where Representative Tim Ryan, a former surrogate for his presidential campaign, is running for a Senate seat and has walked a fine line in discussing Biden, most recently suggesting he shouldn’t run for reelection.

Nonetheless, much of Biden’s focus — and his party’s — has been on the states that would help him keep the Senate in the short run. “If you give me two more Democratic senators in the United States Senate, I promise you — I promise you — we’re going to codify Roe,” he said at a closed-door fundraiser at the National Education Association headquarters last week. That prioritization of the chamber has suited Biden well not only because of his long history in the body but also because Pennsylvania and Georgia are two of the top-three target races for many in his inner circle along with Nevada. (Democrats are in close reelection battles in the latter two and are barely favored to pick up a seat in Pennsylvania.) And in each of those races, Democrats are watching closely to see how voters are reacting to the right-wing Trump allies nominated by the GOP. Beyond the short-term results, those races could provide hints about Trumpism’s appeal in those states in 2024. A Biden adviser confirmed he was watching those closely contested states, intent on divining the limits of “ultra-MAGA” candidates’ appeal.

The elevation of MAGA candidates has dovetailed with a more positive feeling in Democratic quarters since the final weeks of the summer, as they have seen evidence that Biden’s rebounding approval rating and a surge in voter registration among women after the repeal of Roe v. Wade would add up to trouble for Republicans. As Biden’s pollster, John Anzalone, told me a few weeks ago, “Independents make a midterm — that’s the reality of it — and it’s the independents who are particularly competitive. They’re also the ones who are the most undecided and persuadable, especially young independents.”

Considering this calculus, both Arizona and New Hampshire appear friendlier to Democrats now that hard-right Trump followers are entrenched as the nominees in Senate races there. Senator Maggie Hassan’s opponent, Don Bolduc, flipped his position on the legitimacy of the 2020 election as soon as he won the primary, and Democrats believe he erred gravely in a recent interview when, acting as if he were addressing Hassan in responding to a question about abortion policy, he said, “Get over it: This is about the economy, fiscal responsibility, and the safety and security of this nation.” As one top Democrat close to the White House said of that contest, “It’s a suburban-white-women game.”

And in the past few weeks, Biden has turned an eye to gubernatorial races, especially those in states where the top official might be able to stop Trump allies from manipulating the vote count in two years. Although for months the trio of races in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin were assumed to be the highest priorities, since their winners would determine those crucial swing states’ abortion policies and election procedures, only the latter appears to be a top-tier competitive race now because of the fringe views of the underfunded Republicans in Michigan and Pennsylvania.

But Biden has been urging party supporters to keep attention on the gubernatorial contests, even recently telling donors at one private Democratic Governors Association get-together in D.C., “If I were running this time and you were choosing between whether you reelect Governor Carney or me, I’d have to tell you, it’s more important that you elect Carney,” referring to Delaware’s John Carney.

He was being mostly tongue in cheek, and the audience laughed. But Biden quickly got serious again. He was trying to make a point, he said. “It’s more important that the state is able to guarantee they have an election process that functions, that it cannot be manipulated.”