This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

America went to the polls Tuesday for the first midterm election of the Biden era. The nation’s perennial experiment in self-governance remains incomplete; ballots are still being counted, and right-wing conspiracy theories about those ballots are still being formulated. But the broad outlines of the 2022 results are already coming into view. Here are seven big-picture takeaways from this year’s elections:

1) For the president’s party, the key to averting massive midterm losses is, apparently, to keep inflation high and presidential approval low.

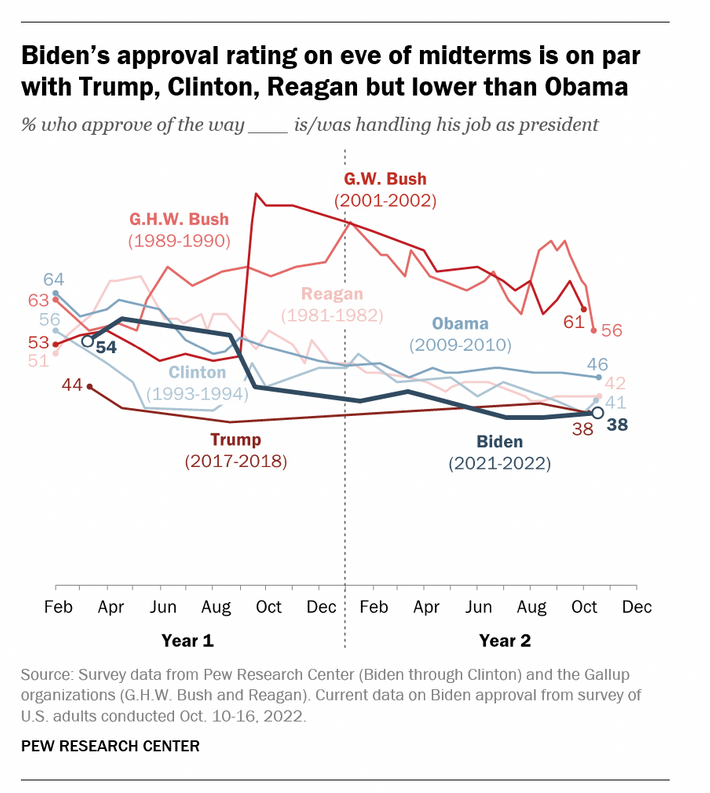

The Democratic Party had many reasons for pessimism going into Tuesday night. On the eve of the midterms, Joe Biden’s approval rating sat near record lows. Pew Research had the president matching the historically poor 38 percent mark that Donald Trump hit in October 2018. That year, Democrats gained 41 House seats in one of the modern era’s largest midterm landslides. Which was not surprising: Historically, presidential approval is strongly predictive of midterm outcomes.

Unlike Trump in 2018, however, Biden did not enjoy the benefit of a relatively strong economy. In September, consumer prices were rising at an annual rate of more than 8 percent. In Pew’s preelection survey, 73 percent of voters said that they were “very concerned” about “the price of food and consumer goods.” Surveys consistently found widespread disapproval of the economy and a Republican advantage on economic issues in general and inflation in particular.

Democrats therefore had cause for fearing that undecided voters would break against them en masse and that a “red wave” would crash over the country, leaving massive Republican Senate and House majorities in their wake.

Unfortunately for some prematurely giddy GOP operatives, this did not happen. To the contrary, Democrats pulled off the strongest midterm performance of any in-power party since 2002.

Republicans will probably take the House. But at present, the New York Times’ analysis of election results projects that the GOP will pick up only 12 House seats. By comparison, in the first midterm of Barack Obama’s presidency, Republicans gained 63.

Senate control remains a toss-up. But Democrats prevailed in the purple state of Pennsylvania and by no small margin. Despite suffering a stroke that severely compromised his capacities for public speaking, John Fetterman is poised to defeat Mehmet Oz by nearly five points. Josh Shapiro, the Democrats’ candidate for governor in the Keystone State, meanwhile, leads his Republican opponent by double digits.

It is still quite possible that Republicans will manage to flip the Senate. As of this writing, the races in Arizona and Nevada remain competitive, while the one in Georgia appears to be headed for a runoff election. If the GOP wins two of those three races, Mitch McConnell will lead Congress’s upper chamber come next year.

But for the moment, Democrats are slightly favored to retain command of the Senate, which could have profound implications; should any Supreme Court justices die or retire in the next two years, a Democratic Senate majority would enable Biden to replace them, while a Republican one would almost certainly prevent him from doing so.

2) Americans don’t like losing abortion rights.

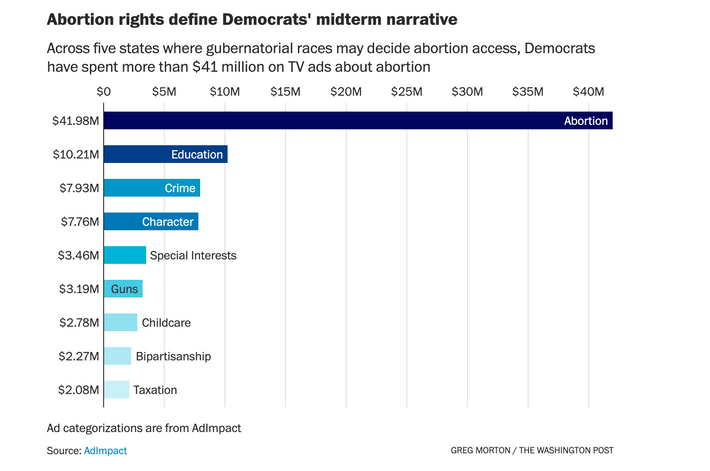

Why Democrats managed to stave off a GOP wave — despite the unpopularity of both Biden and his economy — isn’t entirely clear. But the Supreme Court’s decision to strike down Roe v. Wade is a big part of the story. In an October Washington Post–ABC News poll, 62 percent of voters named abortion as one of their top issues, while 64 percent disapproved of the Supreme Court’s recent decision on the subject. Voters in the survey said that they trusted Democrats to do a better job than Republicans on the issue by a 51 to 32 percent margin.

Democrats took such poll results to heart, spotlighting abortion in their paid advertisements.

This looks wise. Democrats mustered surprising victories in many places where abortion rights are insecure, including, most notably, Kansas governor Laura Kelly’s reelection in that deep-red state. At the same time, the pro-choice movement appears to have secured a clean sweep of Tuesday’s ballot referenda. Kentucky voted down a proposed constitutional amendment that would have established that there is no right to an abortion in the Bluegrass State. Earlier this year, a court in Kentucky had ruled that the state’s constitution includes an implicit right to terminate a pregnancy. Conservatives appealed that ruling. Had the ballot measure passed, progressives would almost certainly have lost the impending Kentucky Supreme Court case on the matter. Now, they like their chances.

In Montana, the pro-choice side is currently poised to defeat a ballot measure that would hold physicians criminally accountable for failing to “make every effort” to save the life of a baby “born alive” at “any gestational age.” In other words, doctors would be prohibited from providing palliative care to a fetal infant born with a heartbeat — but with no chance of survival — whether as a result of severely premature pregnancy or an abortion attempt.

In Michigan, Vermont, and California, meanwhile, voters added a right to reproductive autonomy to their state constitutions.

3) Democracy was on the ballot, and democracy won.

Going into Tuesday, one of the Democrats’ great fears was that Republicans who deny the legitimacy of the 2020 election would secure control over election administration in key Electoral College battleground states. And it remains possible that this will happen in some places; as of this writing, a Trumpist boasts a very narrow lead in Nevada’s race for secretary of State. In Arizona, the Democratic candidate for that position currently enjoys a nearly five-point advantage, but much of the vote there has yet to be tallied.

Still, Democrats won commanding victories in gubernatorial races in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan. In the latter two states, Democrats also lead the races for secretary of State (in Michigan, the party has already won, while the race in Wisconsin remains too close to call). In Wisconsin, the secretary of State does not have authority over elections. But Republicans in the Badger State’s legislature had hoped to win control of that office and then give it control over election administration.

All in all, this looks like a poor showing for the “stop the steal” movement. And if things break right in Nevada and Arizona, there won’t be a die-hard Trumpist in charge of overseeing elections in any of the top-six battleground states.

More broadly, the fact that many of the GOP’s most authoritarian candidates — including Pennsylvania gubernatorial nominee Doug Mastriano — drastically underperformed relative to more banal Republicans establishes beneficent incentives for the party going forward. It turns out, the median voter dislikes violent insurrections against the U.S. government and the conspiratorial delusions that justify them.

4) Voters might not hate the Biden economy as much as they think.

After the 2008 financial crisis, Democrats decided to enact a stimulus that the party’s own economists considered inadequate, in deference to concerns about the national debt. As a result, the unemployment rate remained near 10 percent when voters went to the polls for the 2010 midterms.

In 2021, Democrats decided not to repeat their mistake. Even before Biden took office, Congress had already enacted historically large relief bills, which had prevented the COVID crisis from triggering a depression. Nevertheless, with the virus still rampant, Democrats decided to err on the side of providing American households and state governments with excessive financial support, over the objections of many economists and commentators.

This was probably an unwise allocation of legislative capital. Given that Joe Manchin’s tolerance for new government spending proved highly limited, Democrats probably should have allocated more of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan’s funds to permanent programs and high-impact public investments, rather than one-off checks.

Still, the Democrats’ approach now looks much more politically defensible than it did 24 hours ago. For over a year now, polls have consistently found overwhelming disapproval of the economy and discontent with rising prices. This led proponents of full employment (like myself) to despair. In our view, paying for the real economic costs of the pandemic through inflation, rather than mass unemployment, was the just thing to do. It distributes the material burdens of the COVID shock more equitably instead of concentrating it on the most disempowered members of the labor force. But for precisely this reason, it appeared to be politically toxic: Since everyone feels the sting of rising prices, while only a minority of the public suffers from high unemployment, voters looked poised to punish Democrats for prioritizing tight labor markets over low prices.

If voters did this, however, the punishment looks awfully mild. Although there are many other variables that could explain the divergent outcomes, Democrats did far worse in the “low inflation, high unemployment” environment of 2010 than in the “high inflation, low unemployment” one of 2022.

It is possible that the Biden economy makes voters cranky without rendering them desperate for change. Yes, prices are annoyingly high. But wages have almost kept pace with them and jobs are abundant. It’s plausible that these conditions conferred a sufficiently strong sense of material security to prevent many swing voters from reflexively demanding change. (The fact that the GOP’s only explicit plan for reducing inflation is heinously unpopular might have also helped.)

5) Florida is no longer a swing state.

To be fair, it is not quite accurate to say that there was no “red wave” Tuesday night. There was one. But it flooded Florida and then promptly washed back out to sea.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton won Miami-Dade by nearly 30 points. In 2018, Florida governor Ron DeSantis lost the 70 percent Hispanic county by more than 20 points.

But in the 2020 election, Donald Trump made big inroads with Hispanic voters in general and with those of the Sunshine State in particular. And at least in the latter case, that was no one-off phenomenon: As of this writing, Miami-Dade County is favoring DeSantis for governor by an 11.4-point margin and Marco Rubio for Senate by a 9.5-point one.

In 2016, few would have predicted that the election of the most openly racist Republican president in modern history would trigger a rapid realignment of Hispanic Floridians toward the GOP. But, for whatever reason, something like this has happened. And the swift collapse of the Democrats’ advantage with Latinos in Miami-Dade has effectively ended Florida’s long tenure as a swing state. At this point, there is little reason for Democrats to invest scarce resources in the Sunshine State instead of in increasingly competitive Sun Belt battlegrounds like North Carolina and Georgia.

This narrows the Democrats’ path to victory in the Electoral College somewhat. But it also liberates the party from the imperative to cater to Floridians’ idiosyncratic foreign-policy concerns. Joe Biden no longer needs to pretend that America’s embargo of Cuba will surely bring down its communist government, if only we give it another 60 years.

6) Donald Trump probably isn’t going to waltz to the nomination in 2024.

Following his landslide reelection Tuesday night, Ron DeSantis gave a victory speech that sounded an awful lot like a 2024 campaign launch. Given that the Florida governor led his state party to a sweeping victory on an otherwise disappointing night for Republicans, DeSantis’s stature within the GOP has never been higher. He should have little trouble attracting plutocratic patrons and activist support for a presidential campaign.

Trump’s Tuesday night was decidedly less favorable. The ex-president endorsed both Mastriano and Oz in Pennsylvania, saddling his party with nominees whom GOP consultants considered exceptionally weak. Trump’s handpicked candidate for Michigan governor, Tudor Dixon, got blown out, and his favored GOP congressional candidates underperformed. Republican secretary of State candidates who took up the mantle of Trump’s election lie tended to do worse than their state’s partisanship would have predicted.

For much of the GOP’s political class, Trump commands loyalty out of fear rather than love. Many Republican operatives still long to liberate their party from an interloper who cares less about advancing conservative ideology or maximizing GOP power than about cultivating his own personality cult. Tuesday’s results may help them persuade Republican primary voters that Trump is simply a bad bet in 2024.

7) Ticket splitting is real (and candidates matter).

American politics have grown increasingly polarized and nationalized. The two parties are about as distinct ideologically as they’ve ever been. And as local newspapers have been displaced by nationally oriented partisan media, voters have become far less inclined to vote for one party at the top of the ballot and the other one for lesser offices.

But these trends can be exaggerated. Rates of ticket splitting may have declined. But there are still a great many voters who support Republicans for some positions and Democrats for others. And since the American electorate is narrowly divided between the two parties, these swing voters wield decisive influence over elections. Indeed, early analyses of Tuesday’s election suggest that the Democrats’ success Tuesday night derives less from turnout than persuasion: The electorate yesterday was significantly more Republican than Democratic in terms of party registration, but it did not vote that way.

In many battleground states, a large chunk of voters demonstrated that they do not toe either party’s line but rather evaluate races on a candidate-by-candidate basis. In Pennsylvania, Democratic governor Josh Shapiro is poised to win by several points more than Fetterman, a fact that likely reflects the extremism of Shapiro’s Christian-nationalist opponent, Doug Mastriano. In Ohio, meanwhile, Republican governor Mike DeWine currently leads his Democratic opponent by 26 points. And yet Democratic Senate candidate Tim Ryan is on pace to lose his race to Republican J.D. Vance by fewer than six points, a result that validates Ryan’s messaging strategy and casts doubt on Peter Thiel’s eye for political talent.

And in Kansas — a state that backed Donald Trump by nearly 15 points two years ago — Democratic governor Laura Kelly won reelection.

From a certain angle, this too represents good news for the Democratic Party. The existing Democratic coalition is badly underrepresented in the U.S. Senate, which gives disproportionate influence to less educated, rural voters. Thus the more voters are willing to judge candidates by their personal ideological and characterological profiles — rather than solely by their partisan identification — the better the Democrats’ prospects of remaining competitive in the race for Senate control (even after Joe Manchin is no longer around).

Tim Ryan ultimately failed to paint the Buckeye State blue. But he wasn’t necessarily the ideal candidate to do so. During his ill-advised presidential run in 2020, Ryan had courted the national Democratic-primary electorate, a decidedly different constituency than swing voters in his pro-Trump state. Had Ryan’s entire political career been defined by the heterodox, pro-labor politics that characterized his campaign, it is conceivable that he could have prevailed — especially if he’d run in a better year for Democrats nationally than 2022.

What’s more, Fetterman’s strong showing in Pennsylvania suggests it is possible for Democrats to cater to (at least some) regional electorates without forfeiting progressive policy ambitions. Fetterman famously endorsed Bernie Sanders in 2016 and is a staunch advocate of marijuana legalization, criminal-justice reform, and filibuster abolition. He is quite plainly to Joe Biden’s left ideologically. And yet, in a less favorable national environment than 2020, while suffering from stroke-induced disabilities, Fetterman managed to win Pennsylvania by a larger margin than Biden did two years ago.

If Democrats find candidates who can appeal to the peculiar interests or affinities of their respective regions, there’s no telling where the party could compete. Except for Florida. Florida’s probably gone.