The Republican Party has beat a retreat in its war on the formal institutions of democracy. In November, virtually every failed GOP candidate accepted the legitimacy of their defeat, while several Republican state officials who had refused to abet Donald Trump’s attempts at election subversion comfortably won reelection.

It shouldn’t be notable for a major political party to affirm the validity of election results or renominate officials who prioritized the constitutional order above the delusions of their party’s standard-bearer. But two years after a majority of House Republicans refused to certify the 2020 election’s results — hours after an insurrectionary mob nearly bloodied their colleagues — it is.

Still, ceasefires shouldn’t be mistaken for peace.

It is possible that the Republican Party has lost its appetite for outright sedition. After all, the GOP’s flirtations with insurrection did not derive from the party’s deep-seated ideological commitments so much as from its leader’s contingent compulsions. Red America’s top leaders and donors did not coalesce around a plan for invalidating the 2020 election. Rather, the narcissist-in-chief started spouting conspiracy theories that would safeguard his self-image against the prospect of defeat, and Republicans then scrambled to stay on the right side of his personality cult.

Trump may not win renomination in 2024. And the GOP may never again evince as much interest in thwarting the peaceful transfer of power as it did two years ago. But if the Republican Party has grown less hostile to democracy’s formal structures, it remains as antagonistic as ever to its actual substance.

The conservative movement’s antipathy for popular sovereignty did not begin with Donald Trump, but rather the New Deal. The modern American right was born to defend the anti-majoritarian preferences of reactionary business elites. And although it has undergone many transformations in the 90 years since FDR’s election, maximizing the wealth and power of such elites remains the movement’s core commitment. If anything, the myriad culture war concerns that have displaced “small government” themes in the right’s messaging have only increased the legislative centrality of its plutocratic project. In the Trump era, congressional Republicans could not agree on immigration policy or the propriety of the president’s Twitter feed. What gave the party common purpose and a governing agenda was its unifying desire to slash taxes on the wealthy and corporations, at a time of historically high inequality and corporate profits.

Similarly, after airing a weeklong infomercial for the party’s disunity and dysfunction on C-SPAN, the House’s new Republican majority is coalescing behind a plan to lower taxes for the rich while gutting social spending on the poor and elderly.

Early last week, CNN’s Annie Grayer obtained a slide from a closed-door Republican meeting that laid out the party’s fiscal priorities for the new Congress. These include balancing the federal budget within 10 years and reforming “mandatory spending programs” (a.k.a. Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security). The slide also announces the GOP’s intention to coerce Joe Biden into implementing these policies by threatening to force the United States into debt default if he refuses.

Meanwhile, House Republicans have already voted to slash funding for the Internal Revenue Service, a policy that would increase the federal deficit by undermining tax collections. Kevin McCarthy’s caucus is also preparing to vote on legislation that would abolish the federal income, payroll, and estate taxes, and replace them with a single national sales tax. Such a reform would shift the burden of financing the government away from the rich and onto the poor and working-class, as the latter spend a much higher share of their income on consumption than the wealthy do.

Balancing the federal budget in 10 years would require draconian cuts to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, even if existing tax rates were sustained. Erasing the federal deficit while cutting taxes on the rich and corporations would almost certainly necessitate large benefit cuts for Social Security and Medicare’s existing beneficiaries.

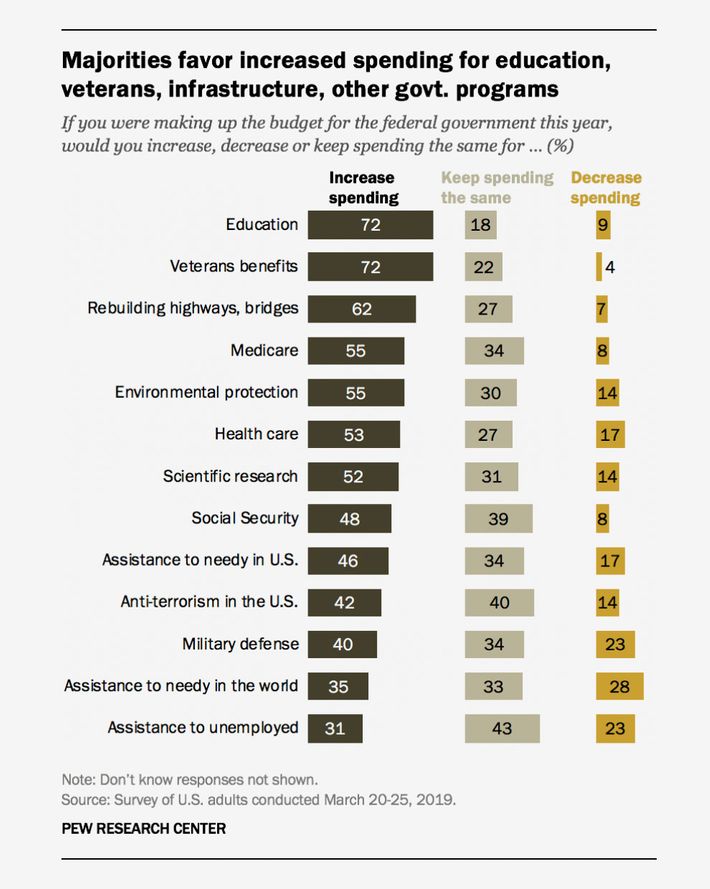

The unpopularity of this agenda is so profound as to challenge the descriptive powers of human language. As of 2021, an overwhelming majority of Americans believed that wealthy people and corporations paid too little in federal taxes. Meanwhile, only about 8 percent of Americans favor cuts to Medicare or Social Security, while a majority of Republican voters approve of Medicaid.

Issue polling can be unreliable. But the Republican Party’s own behavior betrays a belief in the accuracy of the aforementioned surveys. Throughout the 2022 midterm campaign, Republicans said little about their fiscal agenda, focusing instead on purely negative critiques of inflation. Further, in previous elections, the GOP has not merely declined to convey its interest in cutting entitlements, but disingenuously criticized Democrats for hobbling Medicare.

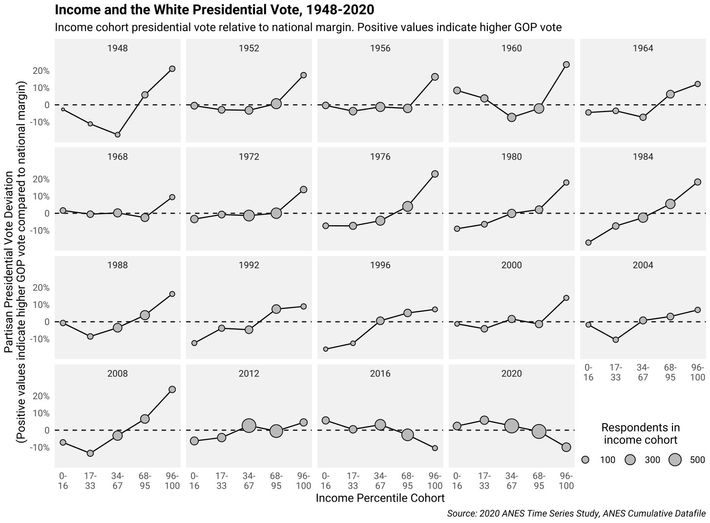

There has never been a majority coalition in the United States for raising taxes on the working-class and reducing healthcare benefits for the elderly. But the contemporary Republican coalition is an especially poor fit for its regressive agenda. In the years since Donald Trump first won the Republican nomination, Red America has grown increasingly blue-collar.

In 2016 and 2020, Republicans actually performed better with white voters in the bottom two-thirds of the income distribution than they did with whites in the top third. In fact, Trump actually did better with the very poorest white voters in America than he did with those in the top 5 percent.

In a remotely healthy democracy, there would be no way to reconcile the Republican Party’s voting base with its fiscal priorities. If Americans had an accurate understanding of their elected representatives’ policy goals, and the interest and resources necessary for holding those representatives accountable to their own preferences, the GOP as we know it could not exist.

Perfect information would not turn every working-class voter into a Democrat, of course. Conservatism, broadly construed, does not lack popular support. Plenty of blue-collar Americans are skeptical of unconditional welfare benefits for the poor and/or hostile to many aspects of social liberalism. But precious few believe that they should pay higher taxes so that the rich can pay lower ones, or that the federal budget should be balanced on the backs of Social Security beneficiaries. In a well-functioning republic, a Republican who supported such positions would not survive a primary.

To be sure, the Democratic Party is not bereft of anti-majoritarian policy commitments. But its core legislative agenda evinces far greater concern for popular preferences than the GOP’s. Under Trump, Republicans used full control of the federal government to push historically unpopular cuts to Medicaid and corporate taxes. Under Biden, Democrats used such authority to enact a panoply of popular fiscal policies. This discrepancy is reflected in the disparate messaging strategies of the Democratic opposition under Trump and the Republican one under Biden. The former focused relentlessly on the substance of the incumbent president’s legislative goals, assailing the implications of his healthcare program. The latter largely ignored the president’s governing agenda, focusing instead on complaints about macroeconomic conditions and cultural controversies.

The Democrats’ greater sensitivity to popular opinion does not derive from the party’s inherent virtue. Rather, it reflects blue America’s relative independence from reactionary billionaires and its coalition’s structural disadvantages. Due to the pro-rural biases of the Senate and Electoral College, the modern Democratic Party cannot win national power without securing roughly 52 percent of the popular vote. And it cannot pass federal legislation without securing the cooperation of legislators who represent Republican-leaning areas. This compels the party to heed majoritarian preferences. And that, in turn, gives the party an incentive to accurately communicate its own governing priorities and those of the GOP.

Conversely, the overrepresentation of rural America enables the GOP to win national power and make federal policy without securing majority support. This makes it a bit easier for Republicans to maintain their anti-majoritarian commitments. Although reconciling those priorities with electoral imperatives still compels the party to reduce the salience of its fiscal goals through culture-war diversions and outright mendacity.

Thus, whether we are living in the aftermath of the Trump era or merely its intermission, the GOP will remain democracy’s adversary. The party must undermine the mechanisms of responsive government — a broadly trusted nonpartisan media, civic organizations with mass working-class memberships, a public discourse centered on those policy conflicts that have the largest material stakes for the general public — or forfeit its ideological project. As the House GOP made clear this week, Republicans have no intention of doing the latter.