The death of Tyre Nichols while in the custody of five Memphis police officers in early January seemed destined to provoke the kind of explosive public response we haven’t seen since 2020. After she watched footage of the attack, RowVaughn Wells, Nichols’s mother, urged people not to riot. “We don’t need to tear up our city,” she said before the videos were made public on Friday. Memphis police chief Cerelyn Davis seemed motivated by the same concern when she rushed to condemn the assault, saying, “This incident was heinous, reckless, and inhumane.” Local officials were so on edge that calls were placed to the White House, and the president and vice-president issued prompt statements. “We all must recommit ourselves to the critical work that must be done to advance meaningful reforms,” Joe Biden wrote.

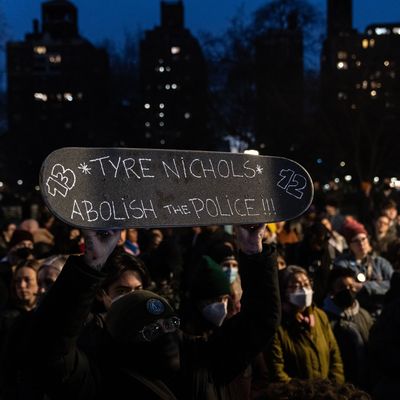

By the time Shelby County district attorney Steven J. Mulroy charged the five officers with second-degree murder, it was clear that fear of rioting had imparted the same lesson on leaders across the country: Look busy. They were rewarded for their anguished displays with a smattering of peaceful protests the weekend after the video was released and no riots. What looked like positive momentum continued when the Memphis Police Department disbanded its SCORPION unit, which had employed all of the officers involved in Nichols’s arrest. Most recently, Nichols’s family was invited to the State of the Union Address on February 7, where they’ll remind viewers of the Democrats’ latest push to pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act through Congress.

The overall effect has been of a brewing storm mercifully averted, clearing the way for the American legal and political systems to operate as they’re supposed to. And that’s part of the problem. Even if the changes currently on offer had been in place before Nichols was killed, they almost certainly would not have prevented his death.

There’s a special perversity to what’s being offered here. The SCORPION unit — an acronym for Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods — isn’t a long-standing pillar of Memphis law enforcement that’s now being reconsidered but a less than two-year-old invention. Amid rising murder rates in October 2021, Davis seized on a growing public enthusiasm for volume policing to flood the city’s highest-crime neighborhoods with less supervised cops. The 40 officers in SCORPION instantly made good on their autonomy, assembling a body of work so prolific that officials bragged about it — 566 arrests by January 2022 — but that amounted, in reality, to “stop and frisk on wheels,” as one local organizer characterized it. Davis’s decision to disband the unit suggests the department has been chastened by its excess. The immediate result, though, will be a return to the excesses that persisted before SCORPION, which included a use-of-force rate against Black Memphians seven times that of white ones.

A more dramatic vision of progress is seemingly materializing at the federal level. Soon after the footage of Nichols’s killing went public, a chorus of lawmakers and public officials began saturating social media with calls to revive the George Floyd Act. “The House must, again, pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act — and this time, the Senate must advance it to the President,” tweeted Nancy Pelosi.

Passed by the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives in early 2021, the bill stalled in the Senate amid a contentious back-and-forth between Biden’s party and a clique of Republicans led by Senator Tim Scott. Negotiations collapsed when Scott walked away, claiming that the Democrats’ demands were too radical even though the component he most objected to — tying federal policing funds to the local adoption of standards like banning chokeholds and no-knock warrants — was initially his idea. The bill would have required ten Republican votes in what was then an evenly divided Senate, so the refusal of lawmakers like Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema to consider eliminating the filibuster sealed its fate. The prospect of getting 60 senators onboard was further undercut by each party’s mutual efforts to cast the other as weak on crime — the GOP by falsely claiming Democrats wanted to “defund the police,” the Democrats by hammering Republicans for supporting Donald Trump’s failed coup attempt.

It’s an acrobatic stretch to assume the bill’s outlook will be any better in the next few months, now that Democrats enjoy a one-vote Senate majority and the House is controlled by Republicans. And that’s besides what’s actually in the bill. The biggest swing in a legally enshrined George Floyd Act would be placing limits on qualified immunity, an untested but potentially useful bid to make cops vulnerable to civil suits. It would also lower the legal standard for finding cops guilty of misconduct — not insignificant but cold comfort when police killings reached record highs in 2022 with Floyd’s killer, Derek Chauvin, sitting in prison. Most of the bill’s other tenets sound eerily familiar, in part because they have already been adopted by police departments across the country: requiring officers at local agencies that receive federal funds to wear body cameras, go through anti-discrimination training, de-escalate before using deadly force as a last resort, and never use chokeholds.

Most of these conditions had been met in Memphis long before Nichols died. The federal government touting them as its big legislative response to his death amounts to doubling down on the city’s deadly status quo. And that’s being optimistic — the more likely outcome is that the bill doesn’t make it out of either chamber and nothing changes at all.

We’d be back at square one with one substantive exception: Officials have gotten more savvy at preempting public outrage. Open condemnation of the cops’ behavior, the expedient publication of visual evidence, swift criminal charges, somber displays of official mourning — all seem to have a pacifying effect. But as far as actual police violence goes, the outcome so far is shaping up to be less a results-oriented reduction than a public-relations strategy to give the impression of progress. George Floyd’s death was a missed opportunity to drastically reduce the footprint of American policing. Tyre Nichols’s is on its way to becoming the same.