The sudden string of bank failures over the past week conjured traumatic flashbacks of the 2008 financial crisis for many a banker. Following Silicon Valley Bank’s unexpected collapse Friday, people on Wall Street and beyond tried to piece together what went wrong and how regulators missed the signs that led to the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history. Then, just before the Oscars Sunday evening, New York regulators announced that they had closed and “taken possession” of Signature Bank, a Manhattan institution relied upon by a couple of major crypto companies (among many other clients, including players in New York’s real-estate market).

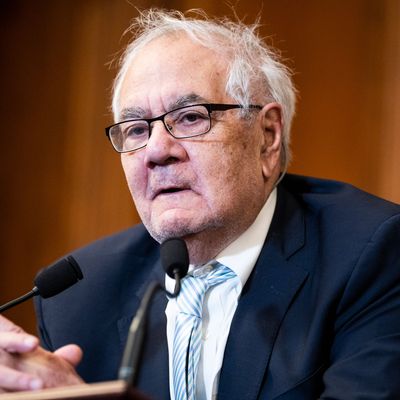

The news blindsided just about everyone, including Barney Frank, the former congressman and architect of the landmark Dodd-Frank banking regulations, who also happens to sit on Signature’s board. The irony of the man who sicced financial watchdogs on the banks now on the losing side of the latest banking crisis was too much for many to resist. Frank was “was having his very own Dick Fuld moment,” Bloomberg wrote, referring to the last chief executive of Lehman Brothers. The Wall Street Journal, meanwhile, sneered with Schadenfreude in an op-ed at the man who kneecapped the banking industry more than a dozen years ago.

Frank, for his part, was quick to suggest that Signature was the victim of a political attack, telling CNBC on Monday that “regulators wanted to send a very strong anti-crypto message.” The New York Department of Financial Services (DFS) on Tuesday pushed back on that assertion, telling Bloomberg it had a “crisis of confidence in the bank’s leadership.” But in a new interview with New York, Frank argued back. Speaking from St. John, Frank explained why he blames regulators for unreasonably putting Signature Bank out of business and what he really thinks about banking crypto — and defended himself against critics who have accused him of switching sides.

Who is to blame for Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse?

I don’t know. I’m not familiar with Silicon Valley Bank, so I can’t tell you. I can tell you from Signature’s part was that it triggered a run on deposits in our bank irrationally. Because whatever Silicon Valley had with regard to high-tech and crypto, we don’t. We’re not a big high-tech lender. We’re a big New York City housing lender more than anything else, and commercial property. We weren’t having crypto as our own asset — we were simply allowing two businesses that were customers of ours that wanted to deal with each other in crypto to do so. We were a facilitator.

But the other part we had was this: We had large depositors way beyond $250,000. That’s because our customer base is made up of major property owners. And years ago when we did the original Dodd-Frank bill, I wanted to extend the deposit guarantee to cover businesses that had to have a lot of cash on hand. I lost on that for a variety of political reasons. So what you had was, Silicon Valley is deteriorating, failing; we are seen by some people as a crypto bank; and, secondly, we have a large number of uninsured deposits. And they panicked and started withdrawing. That’s what happened Friday afternoon.

If the FDIC and the Fed had done on Friday what they did Sunday, we would not have been in any trouble. And secondly, if they’d allowed us to open on Monday, we would have been in good shape; we would have been operational.

The closure of Signature Bank surprised a lot of people, because it didn’t initially seem affected by the run earlier this year at Silvergate, the California-based bank that primarily served the crypto industry.

I’m very disappointed to learn, apparently, the Department of Financial Services in New York, which did the closing, hasn’t said we were insolvent! They said, well, they had a problem, because they couldn’t get sufficient data. I mean, I was disappointed when they closed it, and sort of vindicated — they have not argued that we were insolvent. And I think it’s very clear if we had the benefit of those two announcements, we’d still be an ongoing bank.

Now, the question is, why did they react so harshly to what they said was our inability to give them the sufficient data? I believe it was probably to send the message that even though we were doing crypto stuff responsibly, they don’t want banks doing crypto. They denied that in their statement, but I don’t fully believe that. I think that they overreacted to what they saw was our problem with data, which may well have existed, but the data was improving. I think sloppy data is not a reason to close a bank that you have not decided was insolvent, and they’ve never said we were insolvent.

I mean, is that even legal? Can the government just seize any bank, even if it’s not insolvent?

Well, that’s worrisome. Let me say this. I don’t want to comment on that personally, because as a director, I could be conceivably involved in any kind of lawsuit that anybody brought, but I think that is a very good question you raise. And particularly, somebody ought to look and see, I wonder, are we the first bank to be closed, totally, without being insolvent? And if so, why? I think the DFS, the state of New York people should have to answer that.

That’s why I speculate that using us as a poster child to say “stay away from crypto” was the reason.

Were there any warning signs that the government was planning an action against Signature Bank? Because the NY DFS was reportedly considering closing it last week, before the bank run.

No. I was at a meeting with the regulators a few weeks before, in the middle of February. There was nothing suggested that we were in danger of being closed or etc. There was no indication of that then. Hard to see what happened in a week.

Do you see this as maybe the beginning of a larger crackdown by the government?

No, I don’t think they have to. I think that there’s already a retreat by banks from crypto. There’s an old French expression — they were interested in the 18th century, how strict the discipline was in the British Navy, and in one case, the British Navy executed a guy for a relatively minor infraction because they were worried about the behavior of all the sailors. And the French said, “Oh, those peculiar English. They shoot one man to encourage the others.” And that phrase, pour encourager les autres, people understand what that means. And I think it’s probably working.

You’ve said regulators are sending a strong anti-crypto message to the banks. Do you think that that attitude is misplaced?

I think it is misplaced to say that there’s no way a bank can do crypto. We did it in a reasonable way. We weren’t counting on the value of crypto ourselves. We were facilitating other people doing it. I will say I am skeptical of crypto in general and always have been. And I think what you need is much tougher regulation of crypto, but not by the banks — by the SEC. And the Fed.

There’s a lot of talk about the weakening of Dodd-Frank in 2018, and Elizabeth Warren has blamed that for the recent failures of banks like SVB. Do you agree?

Congress raised the dollar amount by which you got strict scrutiny. But I also don’t think that there was anything that wasn’t quite caught as a result of that. They were still regulated. I was on the board of Signature before and after that bill went into effect. I can guarantee you there was no diminution of regulation. And, in fact, it was the state of New York that stepped in, and they were not affected by the 2018 bill. If there was something that should have led them to do it earlier, they had in 2019 every power they had in 2013.

Finally, I do want to say from my own personal standpoint, I came to the conclusion in 2012 that $50 billion — the minimum amount of assets banks needed for Dodd-Frank to apply — was too low and was arbitrary. So I made a speech in 2013 to a conference that the Federal Reserve had in Chicago saying two things: One, that we had to protect small banks and exempt them from the Volcker Rule, which we did. And two, that we had to raise the $50 billion. I say that because if you read the paper, it sounded like, oh, I did that to help Signature. I came out publicly for raising the $50 billion two years before I’d ever heard of Signature.

Now people are saying we need more banking regulations, particularly on midsize banks. Are banks underregulated?

I think the power is there. I think what you may want is the regulators to do more. It’s possible that under Trump, they weren’t as tough. I do think if there’s a need for tougher regulation, they have the power to do that. What they did in 2018 didn’t reduce the powers of the banking regulators. It removed the requirement that they be extra careful with the midsize banks, but they still had all the powers if they found anything wrong to act. Nobody’s pointed to me a legislative change you need, except, I would say, raising the level of the FDIC deposit guarantee.

Do you feel that the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit is outdated?

Here’s the deal. It used to be $100,000. In 2008, the FDIC, dealing with the financial crisis, temporarily lifted it to cover businesses, so with banks failing, they wouldn’t withdraw. In fact, if you’re not insured, you withdraw, you go to the biggest bank. It’s good for JPMorgan and Bank of America, and bad for everybody else. When we did our bill, I wanted to continue that. I don’t have an exact number, but I do want businesses that have cash, including payroll needs, to be able to have enough guaranteed, so they don’t have to withdraw during the panic. I lost out to that. The biggest banks and their political influencers want to keep it low — the lower the guarantee, the more they think they have a comparative advantage. I wanted it changed.

I hope going forward, people now understand the argument we were making. I hope that my colleagues, my former colleagues, will now legislate — and I notice even Elizabeth Warren, with whom I disagree some, agrees on this — that they should change that limit. Not for personal; we’re not talking about pocket money for a millionaire. We are talking about a business that has a need for cash flow to run the business. I would say for at least two months they should be allowed to get a guarantee, giving them a chance then to rationally deal with any issue.