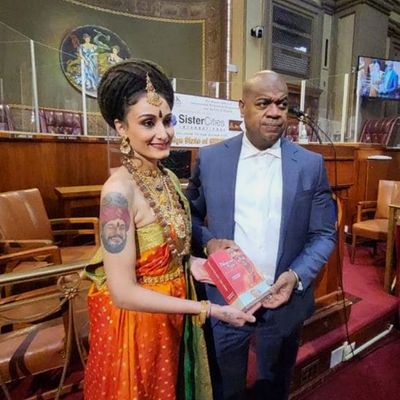

On January 12, Newark mayor Ras Baraka appeared before cameras in City Hall for a signing ceremony to establish a new sister city. In front of a banner extending a “special welcome” to the Sovereign State of Shrikailasa, he said he hoped a cultural exchange between Newark and Shrikailasa would help improve “the lives of everybody in both places.”

The only problem is that Shrikailasa isn’t a place at all. It is neither a city nor a country but the name of the “great cosmic borderless” nation for a group known as Kailasa. They follow the Hindu swami Nithyananda, who claims to be the living embodiment of Shiva. Over the past two decades, he has amassed thousands of followers and claims to have “extended campuses” in 150 countries, where adherents practice meditation, yoga, and a form of Hinduism centered around their leader’s miraculous powers — which include his claims that he has delayed the sunrise and can teach cattle to speak Tamil.

As Newark residents have pointed out, none of this is all that hard to find: In November, a former Kailasa member even appeared on Dr. Phil, describing the group as a “cult” that required members to recruit people into thousand-dollar programs. Six days after Baraka signed the symbolic agreement, Newark dissolved the sister-city partnership, describing it as “groundless and void.” The rupture went unnoticed until March, when the blog TAPinto Newark published a story on the embarrassment. Fox News and The Daily Show soon ran segments on the ordeal, and Newark took the hit for falling for the plan.

But New Jersey’s largest city is far from alone. For close to 20 years, Kailasa has been scamming local, state, and national governments into signing sister-city programs and other unofficial proclamations. The past two years have been particularly active, including a letter of support from Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau for Kailasa’s Hindu Heritage Month celebration, a certificate of special recognition from California Representative Norma Torres, and a “Kailasa’s SPH Nithyananda Day” in Richmond, Virginia. Earlier this month, its representatives spoke at two meetings at a United Nations conference in Geneva — though the gatherings were open to the public and the U.N. said it would ignore their comments. Even after the sister-city program was exposed in the U.S., it continued elsewhere: On March 14, the group signed a cultural agreement with Freetown, the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. “Kailasa and its representatives have not deceived anyone, nor are we fake,” a spokesperson said in a video as the sister-city story gained attention.

At this point, close to 30 U.S. cities have signed some sort of acknowledgement of Kailasa. The plan, in a basic sense, relies on the fact that most cities and government entities are pretty liberal in handing out proclamations, and Kailasa happily promotes its victories on social media. In 2021, the mayor of Fall River, Massachusetts, signed a proclamation establishing a Kailasa Day on January 3, 2022 — with text of the letter written largely by the group itself. “More often than not, requests are accommodated,” said Elaina Pevide, a spokesperson for the mayor’s office. “We probably do one to two dozen a month.”

Pevide explained that the list of prior signatures — as well as the Trudeau letter — helped make the group seem legitimate. It was only when Kailasa followed up to request a sister-city program that Fall River shut it down. “We should probably not be getting a sister-city request from a place we have no relationship with,” Pevide said, noting that the program is usually reserved for cities that share some sort of cultural tie. “I think the words ‘virtual city’ were a red flag as well,” she added. As Kailasa’s sister-city attempts gained attention this month, Fall River’s mayor said it was “my fault” for not being more vigilant.

The experience of Fall River suggests that the letters are meant to build a more legitimate reputation for Kailasa, which has taken significant blows in recent years thanks to the alleged behavior of its leader. In 2010, a follower living in Michigan said Nithyananda raped her on multiple occasions over a five-year period during which they traveled between the United States and India. More women came forward alleging sexual abuse, and in 2013 a purported nondisclosure agreement leaked barring signees from discussing the “learning and practice of ancient tantric secrets associated with male and female ecstasy.” In 2018, the allegation filed by the Michigan woman resulted in a rape charge in Indian court. The next year, Indian police said he fled the country amid an investigation into an alleged kidnapping at one of his ashrams, where 9 and 10 year olds were reportedly forced to work.

Nithyananda has denied all wrongdoing, saying in 2019 that “no stupid court can prosecute me for revealing the truth.” The same year he fled India, reports suggested Kailasa purchased an island off the coast of Ecuador to better establish a nation, but the group now denies that claim, and his current whereabouts are unknown. Journalists who have covered the story believe he may be holed up in a country friendly to Hindu practices like Nepal.

While on the lam, Nithyananda continues to preach online as his followers build out a network of nonprofits within the U.S. and discuss how to build a central bank. The group appears determined to grow despite the legal threats facing its leader, though the number of actual followers remains unclear. In a Wednesday livestream in which Nithyananda told the audience how to realize their New Year’s resolutions, a little over 2,000 people were watching.