The United States is very good at sabotaging itself through policy errors. But few of our nation’s governing failures are as simultaneously needless and detrimental as our inability to build housing.

There are between 1.5 million and 6 million fewer homes in the U.S. than there are households ready to occupy them. The proximate cause of this mismatch isn’t hard to discern: Over the past ten years, the number of housing units per 1,000 people in the U.S. has actually fallen.

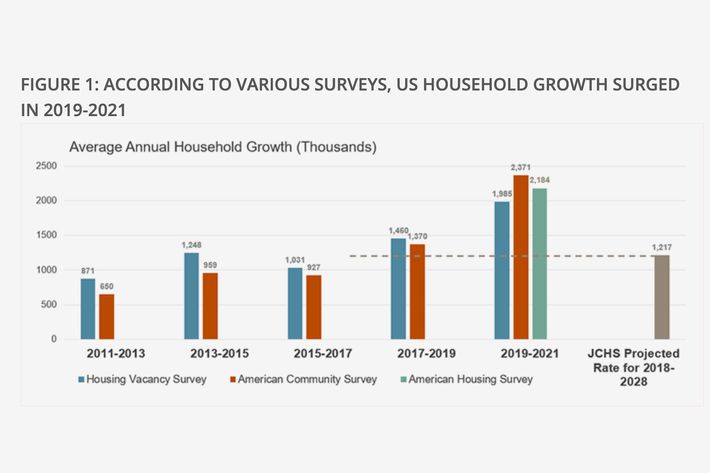

By itself, a rising ratio of people to units would be sufficient to put pressure on housing supply. But since the pandemic, the number of discrete households in the U.S. has also spiked. This phenomenon has multiple causes. One is that much of the millennial generation is aging out of its roommate-tolerating years en masse and starting separate households.

Another is that the rise of remote work has led many Americans to seek more personal floor space, whether by ditching roommates or upgrading from, say, one-bedroom dwellings to two-bedroom ones so as to make room for a home office.

In any case, the upshot of this development is that demand for housing has been rising even faster than population growth would predict. After all, every time a pair of roommates split up and get their own places, they remove one dwelling from the market. And every time a remote worker converts a bedroom into an office, the number of people America’s housing stock can comfortably shelter declines by (at least) one.

It’s not surprising, then, that the average rent in the U.S. has increased by 18 percent over the past five years, far outpacing inflation.

The direct impacts of this housing shortage are many and malign. High housing costs have been displacing households from their longtime neighborhoods and driving more than a half-million Americans into homelessness. Housing scarcity also magnifies inequalities, as Americans who happened to buy a home in a high-demand area decades ago reap windfall wealth gains, while younger, less affluent Americans find themselves locked out of homeownership by high prices and unable to build up their savings due to high rents.

Yet the scale of our folly only becomes clear when the second-order effects of the housing crisis are brought into view. The most productive and economically vibrant parts of the U.S. are also the places where housing supply has lagged most egregiously behind demand. This substantially depresses productivity and economic growth throughout the American economy, as workers who would otherwise secure higher wages by migrating to more productive cities forgo such moves since relocating would increase their housing costs more than their pay.

According to one 2019 study from economists at the University of Chicago and UC Berkeley, if New York City, San Jose, and San Francisco loosened zoning restrictions that forbid high-density housing construction, America’s total gross domestic product would increase by 9 percent. Put differently, average annual earnings in the U.S. would rise by roughly $8,755.

Meanwhile, the unaffordability of major urban centers incentivizes suburban sprawl, thereby increasing the carbon intensity of the average American’s lifestyle and the severity of climate change.

In sum, were it not for the housing shortage, the U.S. would see less displacement, homelessness, inequality, and carbon emissions along with higher wages and economic growth.

In many policy realms, achieving outcomes this beneficial requires overcoming complex technical and logistical challenges. Yet the housing shortage could be greatly ameliorated by simply legalizing the construction of apartment buildings in areas with high levels of housing demand and access to mass transit. This would not be sufficient for realizing housing justice; the market alone is unlikely to ever provide adequate housing to the lower rungs of the labor market. Still, we could make substantial headway on a dizzying number of social problems by ceasing to outlaw apartments throughout much of the country.

Some U.S. cities have taken significant strides in this direction recently. But on the whole, America has still largely refused to stop inhibiting the production of multifamily housing. Given the exorbitant costs of this policy, the question of why we place such a high value on housing scarcity is a compelling one.

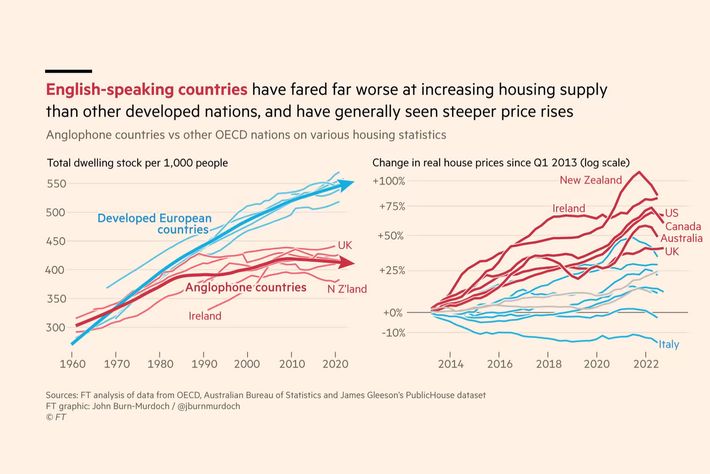

In a recent column for the Financial Times, John Burn-Murdoch offers a counterintuitive answer: Americans speak English.

Burn-Murdoch notes that the United States isn’t alone in its marked antipathy for apartment construction. Anglophone countries have uniformly lagged behind other developed nations in expanding their housing stocks in line with population:

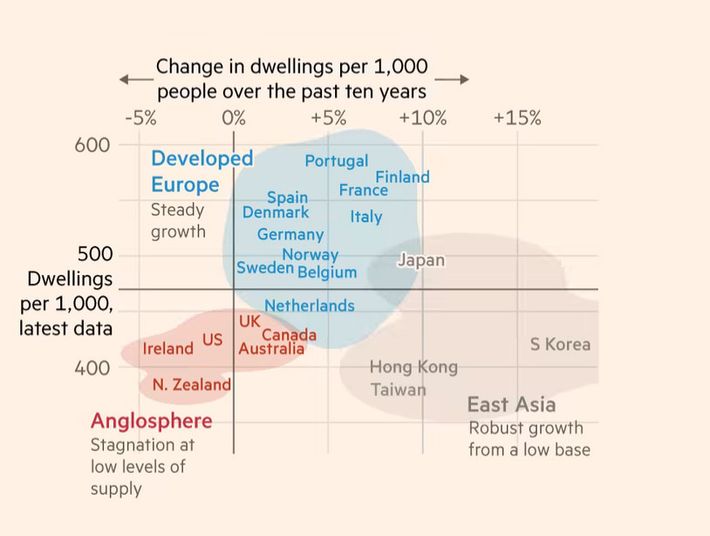

The U.S., Ireland, and New Zealand have all seen their number of dwellings per thousand people decline over the past decade, while that ratio in the U.K., Australia, and Canada has remained largely stagnant. Over the same period, housing per thousand people has increased throughout Continental Europe and East Asia.

Critically, these trends appear to reflect a divergence in public preferences about the kinds of housing that are desirable to live in or near. Relative to residents of other rich countries, Americans and Britons are unusually hostile to the idea of living in or near apartment buildings.

What is it about living in an English-speaking country that turns people against high-rises? Burn-Murdoch posits that England’s colonies inherited the motherland’s peculiar fetishization of private, country living:

[Anglophone countries have a] shared culture that values the privacy of one’s own home — most easily achieved in low-rise, single-family housing. The phrase “an Englishman’s home is his castle” dates back several centuries. From this came the American dream of a detached property surrounded by a white picket fence, while Australians and New Zealanders aspired to a “quarter acre.”

This is a plausible hypothesis. And one could see how an inherited reverence for private, single-family homes might acquire peculiar strength in the U.S. context, where abundant land made widespread ownership of small family farms possible in the early republic, and Jeffersonian ideology celebrated the small landholder as uniquely capable of republican self-government.

This said, there is one big problem with the idea that Americans’ antipathy for living in apartments is the primary driver of our housing crisis: The reason why rents are so high in America’s major cities is precisely because a lot of Americans want to live in apartments in those places.

Americans might prefer to live in our own personal castles, all else equal. But given the unique economic, social, and leisure opportunities afforded by major cities, many of our nation’s suburban homeowners would prefer to live in an urban apartment building, if only they could afford it.

This doesn’t mean that an inherited cultural affinity for single-family housing is irrelevant to our problem. But the key impediment to housing abundance is the way these cultural tendencies have entrenched themselves through our zoning institutions.

In the U.S., we allow local governments to craft their own zoning laws, often through processes that give disproportionate influence to older, wealthier homeowners who have an interest in maintaining high housing prices and no great stake in rental affordability.

Countries with more abundant housing tend to do things differently. Take Japan, which has done an exceptionally good job of expanding housing supply to keep pace with demand (and enjoys relatively low housing costs as a result). There, zoning is set at the national level, enabling the collective interest in abundant housing to override each individual locality’s theoretical interest in minimizing construction noise, traffic, and the like.

The Japanese zoning code is not laissez-faire. High-pollution industrial zones are segregated, and the density of permissible development does vary across space. But projects that conform to the national government’s broad ground rules are permitted automatically. As Burn-Murdoch notes, in both the U.S. and U.K., local authorities have considerable leeway to reject projects on an ad hoc basis, an arrangement that strengthens the hand of local blocking coalitions.

Cultural factors may help explain the origins of these divergent approaches to zoning. But once in place, the zoning process itself becomes the primary impediment to housing supply. And it may also reinforce cultural antipathies for high-density development. After all, in a world of scarce housing and high rental prices, apartment-dwelling will be associated in the popular imagination with cramped and austere ways of life.

Thus, if apartment-phobia is the name of our ailment, zoning reform is what the doctor orders.