The United States is not trembling on the precipice of a communist revolution.

Uncle Sam commands the most powerful military in human history, and its rank-and-file exhibit few socialistic sympathies; U.S. precincts with military bases backed Donald Trump in both 2016 and 2020. America’s civilian security forces — which is to say its roughly 665,000 police officers — are even more hostile to the left than the troops. Our nation’s most heavily armed private citizens, meanwhile, would by and large prefer a Hobbesian war of all against all to a Marxist government. Should America’s constitutional order ever give way to an extralegal power struggle, an overwhelming force of arms will be arrayed against the radical left.

If those contras would have superior firepower, they would also (almost certainly) have more popular support. Some 73 percent of U.S. voters identify as moderates or conservatives. There is some ambiguity about what voters mean when they choose such labels. But it seems safe to say that very few self-identified moderates intend to convey their support for a revolution to establish market socialism, but not anarcho-communism.

In fact, the U.S. electorate evinces a strong bias toward the status quo. When federal policy moves left on a given issue, public opinion tends to move right in response, and vice versa. Support for universal health care hit a modern low after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, while support for abortion rights hit an all-time high after the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

This fondness for stasis can’t be written off as false consciousness alone. America’s political economy condemns a minority of its population to unremunerative labor and/or penury. And our nation’s exceptionally low life expectancy bespeaks its profound social pathologies. Nevertheless, median real household income in the U.S. is about as high as it has ever been, having risen from $60,313 in 2012 to $70,784 in 2021. That leaves the typical U.S. family more prosperous, at least by one plausible measure, than roughly 90 percent of all humans on the planet today (and 99-plus percent of all who have ever existed).

The most damning feature of the present economic order may be the threat it poses to Earth’s climate and ecosystems. And climate change does inspire public concern. But in a 2022 AP-NORC poll, voters were nearly twice as likely to name “gas prices” as a top priority as they were to name any subject related to climate or the environment. This finding is consistent with the U.S. public’s broader political behavior. Much of the country consistently supports a party that is actively hostile to decarbonization. In blue America, meanwhile, voters have repeatedly shot down carbon-tax referenda, while self-avowed climate hawks have prioritized their antipathy for nuclear energy, hydropower, and “upzoning” over reducing carbon emissions.

In other words, the small minority of Americans who say decarbonization is their top political goal won’t reliably sacrifice their sentimental attachment to a particular piece of nature in service of that cause. It is therefore unlikely that they are prepared to sacrifice all the consolations of political stability — and/or their very lives — in support of an ecosocialist insurrection.

Given these realities, intraleft debates over revolutionary versus “reformist” theories of change always strike me as anachronistic cosplay, a bit like model U.N. for enthusiasts of the late-19th-century Social Democratic Party of Germany. Whether one is a stalwart communist or a squishy social democrat (like myself), the fundamental political task seems the same: to narrow the gap between utopia and reality through legislative reforms. Ideally, these reforms would also ease the path to more thoroughgoing progress by, say, strengthening the labor movement or other left-wing institutions. Extra-electoral political activity — from community organizing to civil disobedience to strikes — may be integral to securing such policy advances.

The basic project, however, is to minimize needless suffering within the constraints imposed by the existing constitutional order and political economy while simultaneously chipping away at those constraints. Any attempt to abruptly circumvent those strictures by challenging the government’s monopoly on violence will run into the buzz saw of the modern security state or the overwhelmingly counterrevolutionary sentiments of a prosperous and propertied American middle-class.

But some on the left disagree. Or at least they argue as if they do.

Such leftists disparage efforts to advance progressive goals through incremental reform on the grounds that doing so will not “liberate us from capitalism” or overcome that system’s fundamental logic. Their rhetoric implies that some alternative, easily discerned course of action would meet that Herculean standard. But they rarely bother to specify their program in any detail, let alone subject it to the same scrutiny that they apply to proposals for reform.

One problem with such ultraleftism is that it is annoying. Another, more significant one is that the compulsion to denigrate the stakes of ordinary politics and the merits of actual reforms tends to blur the analytic vision of otherwise insightful intellectuals. There is value in understanding how our economy’s undergirding logic might circumscribe or subvert particular avenues of reform. Inattention to such dynamics can undermine policy design. Dyspeptic Marxist intellectuals can therefore serve as useful critics even if they wish to keep mundane “bourgeois” politics at arm’s length. If such thinkers allow their antipathy for reformists to distort their comprehension of reality, however, they lose their utility.

This problem is well illustrated by two recent critiques of reform efforts in the climate and housing spheres respectively.

Why some leftists believe green industrial policies can’t possibly succeed.

In a commentary for the New Left Review this week, the sociologist Dylan Riley argues that the Biden administration’s attempts to promote decarbonization and green jobs through industrial policy are doomed to failure and that the same could be said of the “neo-Kautskyite” left’s more ambitious vision of a Green New Deal. After all, neither Biden nor reformist socialists “have a credible answer to the structural logic of capital.” Those who comprehend that logic know that “gradualism cannot work” and that the alternative course of action is straightforward: “The commanding heights of the economy — in this period, finance — must be seized at once.” Any other strategy, Riley explains, is doomed to failure.

Riley feels no responsibility to explain how, precisely, the infinitesimal segment of the U.S. population that regards Bernie Sanders as intolerably reactionary is to seize control of high finance, in defiance of the U.S. military, posthaste. In his (apparent) view, all that is required to establish the implausibility of any and all attempts at reform are a few tendentious theoretical premises; all that’s needed to establish the plausibility of revolution, by contrast, is nothing.

Riley’s fatalism about green industrial policy in general, and the Inflation Reduction Act in particular, is rooted in an abstruse theory of the post-1980s economic slowdown in the advanced industrial world. Specifically, it derives from the economic historian Robert Brenner’s account of late capitalism’s crisis of “overcapacity.”

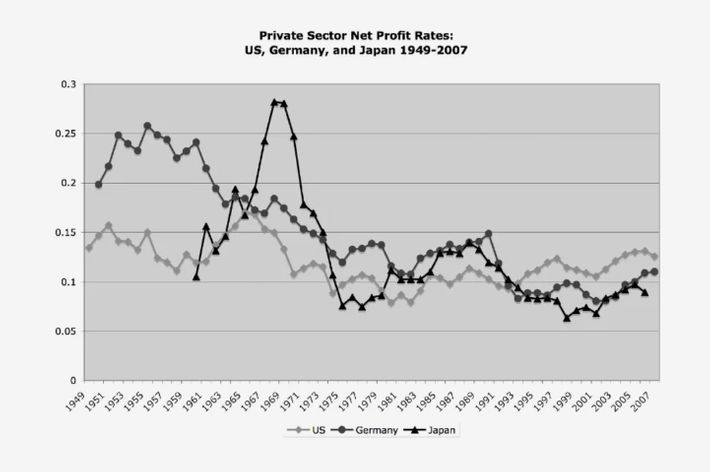

Relative to the postwar decades, the past 40 years have brought low rates of growth in GDP, productivity, and wages in the western world, while the distribution of wealth and income has grown increasingly skewed toward the rich. Brenner attributes this “long downturn” to capitalism’s tendency toward “overcapacity,” which is to say, toward an excess of manufacturing production.

In Brenner’s account, the postwar golden age of American capitalism was made possible by U.S. dominance of world trade. With its industrial peers recovering from total war and the rest of the world still largely agrarian, U.S. firms and their junior partners abroad commanded a manufacturing oligopoly that ensured profitability by restricting competition. Beginning in the 1970s, however, this oligopoly broke down as European and Japanese producers became more formidable and industrialization spread beyond its initial core. An era of ruinous competition ensued.

The fundamental problem was that investments in manufacturing created huge sunk costs. When investors tie up their capital in a factory that specializes in a particular form of production, they are often unwilling to abandon it, even if the price of its produced goods plummets. Thus, as lower-cost producers entered the global manufacturing market, prices and profitability fell, but capacity did not contract in response. As a result, there is now a perennial glut of global manufacturing capacity. This in turn means that capitalists have little incentive to invest in new productive enterprises since the existing ones already yield more than markets can swallow.

For this reason, according to Brenner, the rate of profit in the advanced industrial world has been declining inexorably since the postwar golden age. For Brenner, a falling rate of profit ensures economic stagnation since high profit rates are necessary to induce capitalists to make new investments. And investment is necessary to generate demand for labor and gains in productivity. Thus, overcapacity begets a low rate of profit, which begets a low rate of investment, which begets a low rate of economic growth.

Proceeding from these premises, Brenner and Riley have argued that capitalism (as conventionally understood) has exhausted itself throughout the West. Opportunities for profitable investment are so constrained by overcapacity that the American political economy “does not hold out even the hope of growth” anymore. The pie can no longer be substantially grown, only divided in disparate ways. Capitalists have therefore found that their best bet for securing a return on their wealth is not through investments that increase aggregate prosperity but through political “rip-offs” that redistribute income upward. We have exited conventional capitalism and entered the vaguely “feudal” order of “political capitalism.”

Progressives trying to restore equitable growth through green industrial policy are, therefore, living in the past. Attempting to advance social-democratic reform in the aftermath of neoliberalism is like trying to walk from Australia to Canada after the breakup of Pangea. As Riley explains:

The problem is that neither the Biden administration, nor the neo-Kautskyites, have a credible answer to the structural logic of capital. Imagine, for the sake of argument, that Bidenomics in its most ambitious form were successful. What exactly would this mean? Above all it would lead to the onshoring of industrial capacity in both chip manufacturing and green tech. But that process would unfold in a global context in which all the other capitalist powers were vigorously attempting to do more or less the same thing. The consequence of this simultaneous industrialization drive would be a massive exacerbation of the problems of overcapacity on a world scale, putting sharp pressure on the returns of the same private capital that was ‘crowded-in’ by ‘market-making’ industrialization policies.

How might the US government react to this conjuncture? The response would likely be increased state support, which might take the form of monetary juicing leading to asset bubbles (what Robert Brenner has described as ‘bubblenomics’) or direct profitability guarantees. But this would only exacerbate the phenomenon of political capitalism. That is, directly political mechanisms would become increasingly necessary to generate returns.

Green industrial policy may not work in theory, but it has been working in practice.

There are several problems with Riley’s argument. The first is that the ambitious claims that undergird his entire analysis lack both theoretical coherence and empirical support.

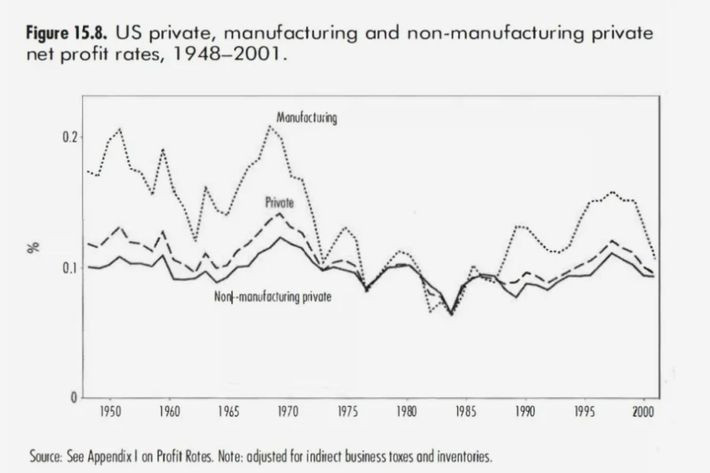

For one thing, as the historian Tim Barker notes, the rate of profit in the U.S. economy has not actually fallen much at all in recent decades. To the contrary, it has oscillated around roughly the same level since the early 1970s, while profit rates in the first decade of this century were comparable to those of the late 1950s.

It is true that the rate of profit in manufacturing has been on a downward long-term trend. But given that manufacturing is responsible for only 11 percent of U.S. GDP, it’s not clear why that sector’s peculiar trajectory is of such overriding importance.

More broadly, overcapacity cannot exist in anything but a relative sense. The world does not have more productive capacity than is required to satisfy all the wants and needs of its 7.8 billion people. Indeed, in recent years we haven’t been able to muster sufficient capacity for meeting consumer demand in the absence of inflation. To the extent that excess productive potential has weighed on profitability and investment in recent decades, this seems better described as a crisis of inadequate demand rather than of superabundant capacity: If ordinary workers throughout the advanced industrial world claimed a higher share of income growth, demand for myriad goods would increase, generating more opportunities for profitable investment in their production.

It is possible that the path to a high-growth, high-investment economy is blocked by political realities endemic to contemporary capitalism, which Biden’s industrial polices are unequipped to overcome. But making that argument requires more than invocations of an inexorable crisis of overcapacity and condescension toward a “neo-Kautskyite” left.

Alas, Riley’s piece offers little else. Before the passage quoted above, the sociologist suggests that encouraging socially desirable forms of productive investment through subsidies cannot possibly work even in the short term. He asks incredulously why investors would “tie up capital in vastly ambitious projects, to promote the green transition” that “will have long time horizons and uncertain returns?”

This is an odd question given the existence of venture capital. In any case, the answer is fairly straightforward: The exorbitantly wealthy can afford to throw money at risky, long-term investments in the hopes of securing windfall returns. Given the expected size of the global markets for electric vehicles, renewables, and other green technologies in the coming decades, such hopes don’t seem absurd on the face of it. Of course, even with Biden’s subsidies, this mechanism might not yield sufficient investment in green technology. But why some investors would tie up their capital in the hopes of owning a piece of, say, the 21st century’s dominant EV producer isn’t hard to discern.

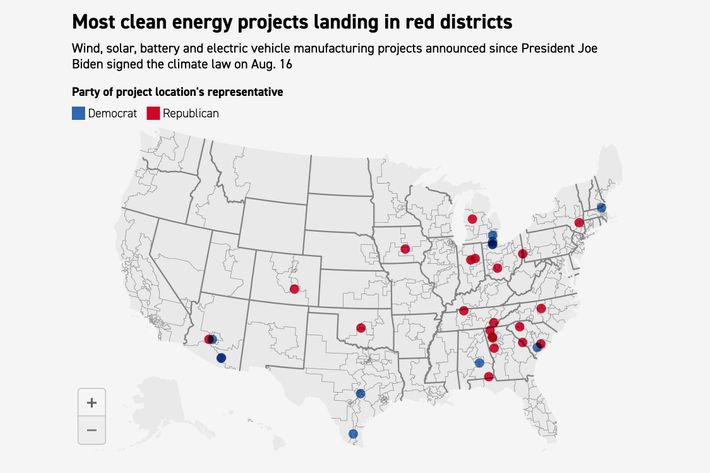

If Biden’s industrial policy cannot work in (Riley’s) theory, it certainly seems to be working in practice: The months since the Inflation Reduction Act’s passage has witnessed a flurry of new wind, solar, battery, and electric-vehicle manufacturing projects across the United States. Politico provides this illustration of the IRA’s apparent impact, which has redounded to the benefit of red America in particular.

Nevertheless, Riley insists that even if Biden’s industrial policy succeeds in the first instance, it will eventually crash into the immovable object of overcapacity. After all, Biden’s subsidization of America’s nascent green industries will inspire other capitalist powers to do the same. This global race to the top will result in “a massive exacerbation of the problems of overcapacity on a world scale” and a concomitant collapse of profit rates.

As the Roosevelt Institute economist J.W. Mason notes, Riley’s argument bizarrely implies that the world has a fixed amount of demand for goods in general and low-carbon technology in particular. But there is no reason to believe this is the case. If capitalist powers the world over bribe investors into launching new semiconductor, electric vehicle, renewable energy, and mining enterprises, those initiatives will increase demand for labor within their economies. That in turn could lower unemployment and raise wages. And when jobless workers start taking home paychecks while others see their incomes rise, their capacity to purchase electric vehicles — or any other good that requires semiconductors or electricity to produce — goes up. Thus, increases in productive capacity can yield increases in demand.

Moreover, the fear that firms will rapidly exhaust global demand for green technology is especially strange. The global transition to electric vehicles, already well under way, is going to exponentially increase global demand for both EVs and electricity. It seems highly unlikely that we are rapidly approaching the point when the supply of renewables will permanently outstrip demand; the wind and solar industries are quite profitable, and virtually every advanced industrial nation plans to increase its consumption of such energy in the future.

To be sure, the capitalist mode of production is deeply vulnerable to crisis and vexing problems of coordination. And Biden’s policies do not adequately address the latter. An optimal decarbonization policy would require more intelligent state planning than America’s politics has been willing to tolerate and than its emaciated state capacity can presently support. Radical critiques that illuminate these problems would be useful. Polemics that cite them as proof of the wisdom of revolution are not.

Perhaps the oddest thing about Riley’s argument, however, is that it barely coheres even if one grants its myriad false assumptions. Let’s say that Riley’s analysis is correct and Biden’s industrial policies will trigger a global glut of low-carbon technology that leaves green industry increasingly dependent on the state’s patronage for its existence. Why wouldn’t that be preferable to the status quo from Riley’s own perspective? Presumably, superabundant wind and solar capacity wouldn’t just weigh on the profitability of renewable enterprises but also that of oil giants. And as renewables become (ruinously) cost competitive, the low-carbon share of power grids would presumably go up.

Separately, it is unclear why private investors growing increasingly dependent on (semi-)democratic states is an outcome that socialists should be preoccupied with avoiding. It seems to me that the more politicized economic production becomes, the easier it is for socialists to contest the terms of that production. Thus, the dubious scenario that Riley sketches is not self-evidently undesirable relative to the status quo. It is only unworthwhile, from a socialist perspective, when juxtaposed with the sudden expropriation of all of finance, an outcome that Riley apparently deems more plausible than a large increase in global demand for solar panels.

Riley is a smart and learned sociologist. His reflections on Donald Trump’s “patrimonial” mode of governance are insightful and amusing. And his critique of Biden’s policies is not entirely without merit. It is certainly the case that the private sector cannot be trusted to make adequate investments in care or education. You don’t need to accept Marxist arguments about a falling rate of profit to recognize that caring for the impoverished elderly will never be a profitable undertaking.

Yet Riley’s ability to function as a useful critic of American liberalism is utterly compromised by his evident preoccupation with discrediting mundane forms of political engagement. In a previous New Left Review essay, Riley and Brenner cited the Affordable Care Act (which increased taxes on capital gains to finance an extension of public health insurance to millions of working-class people) and the CARES Act (which effected a historic drop in the U.S. poverty rate) as examples of “politically constituted rip-off”s that abetted capitalist accumulation through upward redistribution. It isn’t hard to understand why a staunch anti-capitalist might be attracted to the idea that the U.S. economy is incapable of growth, that capitalism has entered an inexorable crisis of profitability, and that any attempt to incrementally reduce the needless suffering of ordinary Americans is hopeless, as the political system is incapable of doing anything beyond reallocating rents between different elites. But that is not an excuse for intellectuals to promulgate such ideas in defiance of evidence to the contrary.

It is good to make housing cheaper, even if that doesn’t liberate us from capitalism.

In a recent column for The Nation, architecture critic Kate Wagner provides a less egregious example of anti-reformist polemicizing. Wagner’s piece is framed as a critique of the naivety of “a certain type of pragmatic liberal urban pundit” who proffers panaceas for America’s housing crisis. Specifically, Wagner aims to push back against the idea that legalizing “single-stair” layouts for high-rise buildings in the U.S. will do anything to reduce housing costs.

In most U.S. cities, large apartment buildings are required to have two separate stairwells as a fire-safety precaution. This regulation effectively forces architects to design floor plans around long central hallways flanked on either side by apartments. By contrast, single-stair buildings — which are the norm in much of Europe — allow for more varied designs. For example, a building can ring units around a central stairwell or atrium, allowing more widespread access to light, air, and cross breezes.

In addition to the qualitative advantages of single-stair design, such buildings offer a more efficient ratio of rentable and sellable housing to overall square footage of space. The plumbing demands of a two-stair building are also more elaborate than those of one-stair project, making the former structurally more expensive to build.

Thus, the two-stair model comes with considerable architectural and economic costs. And it’s far from clear that multiple stairways meaningfully increase fire safety. Many European nations where single-stair designs are dominant have lower rates of fires than the U.S. Mandating sprinkler systems and other low-cost fire precautions would likely compensate for any diminution in safety resulting from a switch to a single-stair standard.

Wagner actually agrees with the pragmatic liberals about much of this. She argues that single-stair hallways are a worthwhile reform but only because they allow for superior architecture. The notion that reducing the costs of new multifamily construction by allowing for single-stair buildings “will do anything to lower rents” is not credible in her view. And she suggests that the same can be said of loosening legal restrictions on multifamily construction through upzoning. The reason for the inefficacy of such reforms is simple: They would not “liberate us from capitalism,” and “the housing crisis stems from an economic system in which housing is a commodity and a money-making scheme instead of a human right to shelter.”

Wagner’s critique of reformism is much more reasonable than Riley’s. It is undoubtedly true that permitting single-stair buildings and upzoning would be inadequate, by themselves, to fully resolve the obscenities of housing insecurity and homelessness in the United States. So long as our economy’s income distribution allows for the existence of individuals with scant housing budgets, private industry will not provide adequate units for all. Any comprehensive plan for housing reform must therefore include social housing.

It is also true that many of the peculiar pathologies of the American housing sector derive from the ideology and political economy of mass home ownership. For generations now, policy has encouraged Americans to regard their homes as investment vehicles. Yet for housing to function as a worthy investment, its price must steadily rise over time. One way to engineer such appreciation is to prevent the housing stock from growing in line with demand by creating regulatory obstacles to housing construction. America’s restrictive-zoning regime is not driven solely by the financial interest of homeowners and landlords in constraining supply. But it is surely one factor.

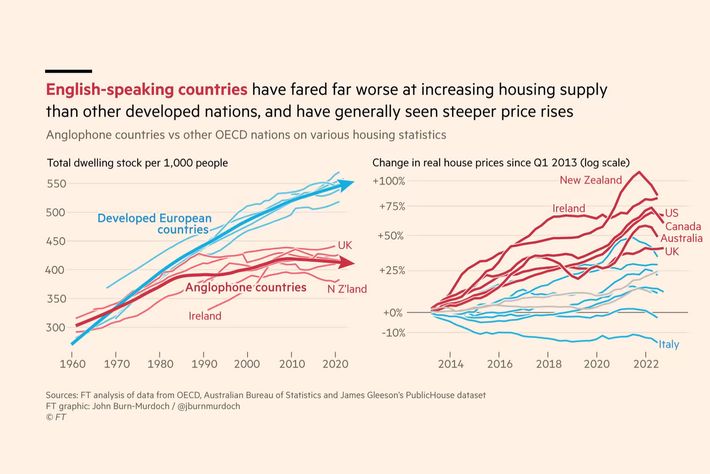

So Wagner is not wrong to suggest that capitalism’s pathologies are implicated in the housing crisis. But it does not follow from that insight that removing obstacles to multifamily-housing construction — such as the two-stair requirement and restrictive zoning — wouldn’t do anything to lower rents. Housing affordability varies between capitalist countries. And capitalist nations that make it easier for developers to grow the housing stock in response to demand tend to enjoy lower prices.

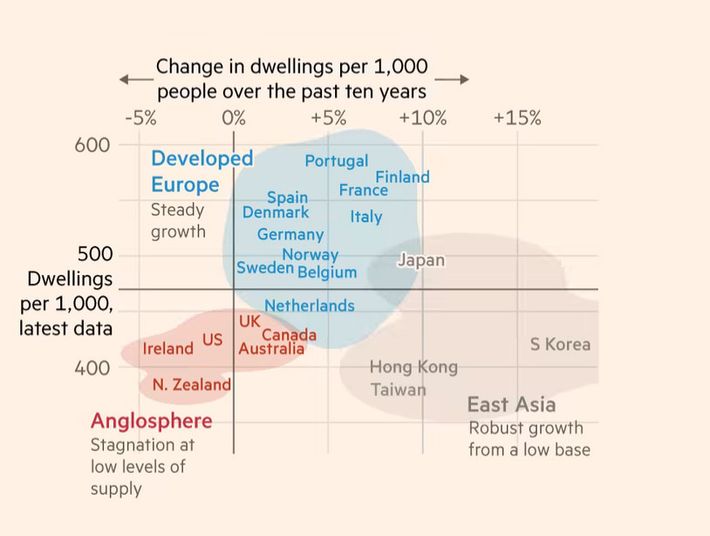

John Burn-Murdoch recently illustrated this point in the Financial Times. Burn-Murdoch contrasted the disparate housing trajectories of Anglophone countries (which tend to have more restrictive zoning codes) and the rest of the developed world. He shows that there is a tight relationship between a country’s ratio of housing units to people and its level of housing inflation.

Abolishing exclusionary zoning and two-stair requirements would almost certainly facilitate more housing construction. And more housing construction would put downward pressure on prices for middle-class households. Further, the easier and cheaper it is to construct new multifamily housing, the more social housing the state will be able to construct with any given amount of tax dollars. There is thus no contradiction between mitigating the housing crisis through regulatory reforms and pursuing the abolition of housing insecurity. Progress on the former abets progress toward the latter.

Like Riley, Wagner does not explain why we shouldn’t prefer such reforms to the status quo, opting instead to explain why we should pursue the abolition of capitalism (or at least the housing market) to such reforms. But she offers no explanation for how the latter is to be achieved. Her warnings about the limitations of regulatory reform are well founded. But her insistence that such measures have no economic value is not.

All of which is to say that the revolution is not coming — at the very least, not on the timeline necessary for keeping climate change within remotely tolerable bounds or for redressing America’s housing shortage. Denigrating useful reforms on the grounds that they fail to abolish capitalism is a fine way for iconoclastic intellectuals to communicate their sense of superiority to the squares who engage with mainstream politics. But it achieves little else.