Biden officially launched his reelection bid last month — in the face of dismal job-approval numbers — by describing “the work of my first term” as a “fight for our democracy” that remains unfinished.

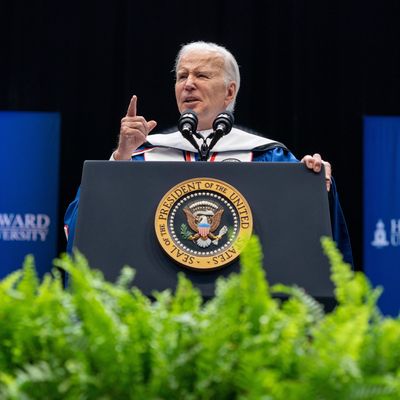

A couple weeks later, when he gave the commencement address at Howard University, he described white supremacy as “the most dangerous terrorist threat to our homeland” while trying to pull together several reelection themes, including the need to “confront the ongoing assault to subvert our elections and suppress our right to vote,” to preserve “fundamental rights and freedoms,” and, more generally, to “put democracy on the ballot.”

The president has obviously made a strategic choice to cast his presidency — and his reelection campaign — in these terms. But that choice also more or less requires an examination of “the work of [his] first term” in this area, and that conversation has been slow in taking shape.

Perhaps that is because, despite the rhetoric in recent years among Democratic leaders about the “fight for our democracy” and the like, the Biden administration and congressional Democrats have accomplished relatively little on this front — so little, in fact, that the man who was supposed to have embodied liberals’ worst fears of anti-democratic rule has a very plausible path to reelection.

Constructing a list of these failures and omissions is not difficult. A push for federal voting-rights legislation fizzled out last year largely thanks to Republican opposition and the filibuster in the Senate, while Republican state legislatures have continued to pass laws restricting access to the ballot. Federal legislative efforts to reform and improve accountability on the part of local police departments have basically gone nowhere. The Biden administration’s support for statehood for Washington, D.C., which would have expanded political rights among hundreds of thousands of residents in the district, was not enough to move the needle in Congress — yet another predictable victim of Senate filibuster rules, which Biden has nonetheless continued to largely support.

The package of good-government reforms in the Protecting Our Democracy Act, which was devised as a response to the Trump presidency, stalled after passage in the House. Meanwhile, the reason that Trump could openly contemplate the return of the family-separation policy at the CNN town hall is that there has been no real accountability for the many government officials who were involved the first time around.

As this has all unfolded, the conservative majority on the Supreme Court has continued to execute the most dramatic reordering of constitutional law in decades, from abortion to voting rights to gun control to, presumably later this year, affirmative action. This was all eminently predictable after Trump reshaped the Court during his presidency, but the Biden administration has consistently resisted any serious effort at long-term institutional reform at the Court — including highly popular proposals like term limits for the justices — and opted instead for a largely pointless bipartisan commission whose inconclusive work on the subject was promptly forgotten.

The Biden administration’s refusal to grapple head-on with the serious problems at the Court appears, perhaps counterintuitively, to be one of the principal reasons that we remain mired in a weeks-long national debate over Clarence Thomas’s apparent ethical failings. Having eschewed the tools that might create real structural change at the Court, the Biden administration has left Democrats to channel their anger with the conservative justices into an abstract discussion over the adequacy of their financial disclosures, even though the real problem — one that will not end anytime soon on our current path and that will not be solved by all the financial disclosures in the world — is that the conservative majority continues to issue wildly unpopular rulings.

On the merits, the nascent effort to construct an alternative, pro-democracy theory of the case for Biden’s reelection bid has so far proven awkward. The launch ad for the Biden reelection campaign made the case by arguing that, “around the country, MAGA extremists are lining up to take on … bedrock freedoms, cutting Social Security that you’ve paid for your entire life while cutting taxes from the very wealthy, dictating what health-care decisions women can make, banning books, and telling people who they can love — all while making it more difficult for you to be able to vote.”

This was a game attempt to pull together something approximating a coherent case, but it does not hold up particularly well against close scrutiny. The Republican Party has been trying to cut social spending and taxes since long before Trump and the rise of “MAGA extremists.” The administration’s efforts to push back on restrictive state abortion laws and judicial rulings have been important, but make no mistake: This is a protracted, rearguard effort to protect against further losses in a decades-long battle over abortion rights. Meanwhile, if the Biden administration has a plan to prevent book-banning by local governments, we have yet to see it; the concern over political actors “telling people who they can love” appears to be an allusion to the possible further erosion of civil rights by the current Supreme Court — the same Court that Biden wants to leave unchanged; and the federal effort to prevent states from making it harder to vote has already failed.

The fact that so much of this ground has been lost or unrecovered at the federal level during Biden’s presidency appears to be one reason that so much interest in recent months among liberals has been focused on state and local political battles — such as the expulsion of two Democrats from Tennessee’s state legislature following a demonstration over gun control, the mistreatment of a transgender lawmaker in Montana after she spoke out against a bill restricting access to treatment for minors, and even Florida governor Ron DeSantis’s battle with Disney.

All of these disputes have been coded in certain precincts of the media as implicating a broader battle over freedom and democracy in the country, but there is little to nothing that the Biden administration can actually do about any of them except to publicly criticize the state Republicans involved. A cynic might conclude that these and other similar fights are being used by some national Democratic leaders as backdoor issues designed to evade or obscure the fact that so little has been accomplished at the federal level.

To be sure, there have been some partial but meaningful steps forward under Biden’s watch. The Electoral Count Reform Act should help to prevent any future effort to overturn presidential-election results that is comparable to the one that Trump and his allies attempted after the 2020 election. The Justice Department’s successful prosecutions for sedition in connection with the siege of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, deserve praise.

The effort to investigate Trump’s possible criminal misconduct in the run-up to that day’s events appears to be in full swing, but even that was so needlessly delayed that it is now highly questionable whether a federal indictment, even if one comes relatively soon, would prevent Trump from being reelected. (Indeed, if Trump is federally charged and manages to win reelection, it should not be particularly hard for him to put an end to the case shortly after retaking office.)

Biden has a ready-made response to anyone who might question his effectiveness as a leader: “Don’t compare me to the Almighty,” he likes to say. “Compare me to the alternative.” This is a simple but serious argument, one that may ultimately have enough traction to carry him to reelection in a general-election matchup against Trump.

There is also a very long way to go until next November, which means that if there is a positive vision for the future of our democracy that does not simply mean always voting for Democrats, there is time for Biden and his party to start trying to articulate that agenda.