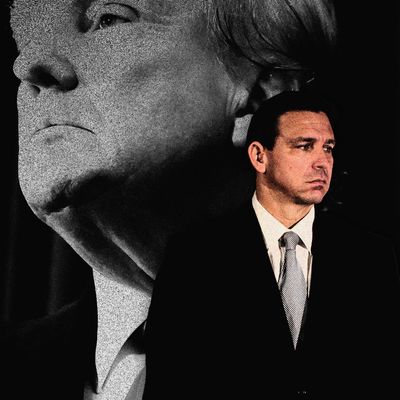

Ron DeSantis’s path to the Republican nomination is littered with obstacles.

Chief among these is Donald Trump’s resilient popularity in Red America. The former president is by far the best known and most trusted candidate in the GOP primary field. And although his loss to Biden in 2020 (and his fumbling attempt to foment an insurrection to avenge it) have soured many GOP elites on the billionaire, the Republican rank and file still regard him as a winner. As of this writing, 54 percent of GOP voters back Trump’s renomination in FiveThirtyEight’s polling average, which puts him more than 30 points ahead of DeSantis. Given that Trump failed to lose a single point of support upon being found civilly liable for sexual abuse earlier this month, it would presumably take extraordinary events for the ex-president to fall behind the Florida governor.

If Trump’s popularity is the primary impediment to DeSantis’s nomination, the Florida governor’s personality is a close second. By most accounts, DeSantis is a virtually friendless introvert who’s infinitely more at home reading conservative policy journals than shaking hands. His voice is nasally, his persona humorless, and his oratorical skills banal. Donald Trump is antisocial and rhetorically inept in his own ways, of course. But he’s also an entertainer with a gift for insult comedy. Trump is typically comfortable on a stage and in his own skin — or at least, he typically projects such comfort. DeSantis does not.

The trouble with DeSantis’s public speaking lies as much in its content as in its style. Part of DeSantis’s pitch to GOP voters is that he, unlike Trump, is a conservative true believer fluent in all of the movement’s myriad obsessions. But this asset becomes a liability when the candidate’s immersion in right-wing discourse renders him illegible to the millions of Republican voters who do not religiously read National Review.

DeSantis’s decision to launch his campaign via a (glitch-riddled) Twitter Spaces dialogue with Elon Musk and David Sacks was testament to the Florida governor’s peculiar sensibilities. The vast majority of Americans are not on Twitter. And the vast majority of Twitter users have never used its audio function. The disadvantages of this unconventional campaign launch were obvious: DeSantis forfeited control of the proceedings to a narcissistic megabillionaire, lost the opportunity to appear before a crowd of cheering supporters on a scenic Florida beach, and called attention to his distinctly non-mellifluous voice. The ostensible benefit was to align DeSantis with Musk, newly rebranded as the patron saint of Red America’s terminally online. It is unclear why the candidate wished to give this alignment priority.

In any case, DeSantis’s remarks were narrowcast at the platform’s idiosyncratic constituency. The Florida governor raged against YouTube’s content-management decisions, Disney’s support for “gender ideology,” and Joe Biden’s crusade against bitcoin. He decried ESG — the movement among investors to consider environmental, social, and governance factors (however superficially) when allocating capital — without ever defining that acronym. It isn’t crazy for DeSantis to make some gestures toward die-hards at this stage in the presidential race, when candidates are competing less for voters (virtually all of whom aren’t paying attention) than small-dollar donors. Yet DeSantis did not switch to a more accessible rhetorical mode when speaking on Fox News later in the day, instead railing against “cultural Marxism” and “ESG” without explicating those terms.

A third obstacle facing DeSantis’s primary campaign is the imperative to simultaneously attack Trump (who will need to be damaged in order to be stopped) and retain the respect of his sympathizers (without whom DeSantis cannot win the nomination).

The Florida governor hopes to execute this balancing act by focusing his indictments of Trump “on substance.” Unlike his adversary, DeSantis is not looking to demean his rival. Rather, DeSantis aims to persuade Republican voters that he is a more reliable vehicle for securing conservative policy wins because he is both more ideologically committed to conservatism and more electorally appealing to swing voters. As the New York Times reports:

[DeSantis] is telling Republicans that, unlike the mercurial Mr. Trump, he can be trusted to adhere to conservative principles; that Mr. Trump is too distractible and undisciplined to deliver conservative policy victories such as completing his much-hyped border wall; and that any policy promises Mr. Trump makes to conservatives are worthless because he is incapable of defeating President Biden.

This is a reasonable gambit. To the extent that there is a way for a non-Trump candidate to win the nomination of a party beholden to his MAGA brand, portraying oneself as the more effective agent of Trumpism may be it. And DeSantis’s success in imposing a laundry list of right-wing reforms on a (at least formerly) purple state lends credence to this appeal.

Nevertheless, DeSantis’s pitch contains a basic contradiction: The more persuasively he establishes his greater fidelity to the conservative movement, the less credible his claim to supreme electability becomes.

At present, the most salient policy divide between Trump and DeSantis concerns abortion. While the former president is keen to advertise his success in overturning Roe v. Wade through judicial appointments, he has also sought to distance himself from the pro-life movement’s furthest-reaching ambitions. This is partly a consequence of the GOP’s disappointing showing in the 2022 midterms. In the aftermath of those elections, with many pundits attributing Republicans’ losses to the unpopularity of their position on abortion, some conservatives insisted that the actual problem was Trump: both his elevation of weak general-election candidates in key Senate and gubernatorial races, and the toxicity of his personal brand with key swing voters.

Trump was, of course, eager to push back on this narrative. In January, he wrote on Truth Social, “It wasn’t my fault that the Republicans didn’t live up to expectations in the MidTerms … It was the ‘abortion issue,’ poorly handled by many Republicans, especially those that firmly insisted on No Exceptions, even in the case of Rape, Incest, or Life of the Mother, that lost large numbers of Voters.”

In the ensuing months, Trump has disavowed the pro-life movement’s push for a national abortion ban, saying that the issue “should be left to the states.”

As the GOP front-runner, Trump has the luxury of prioritizing general-election concerns above activists’ enthusiasm. So long as Trump is the favorite to win the Republican nomination, pro-life groups have an incentive to temper their criticism, so as to maintain the goodwill of the likely standard-bearer.

A candidate looking to close a 30-point gap in a GOP primary, by contrast, has no choice but to try and capitalize on the distance between Trump’s position and the Evangelical movement’s desires. Thus, DeSantis recently banned abortion after six weeks of pregnancy (before many women realize that they are carrying a child) in Florida. Trump responded by claiming, absurdly, that “many people within the pro-life movement” believe that a six-week ban is “too harsh.”

DeSantis has countered, “Protecting an unborn child when there’s a detectable heartbeat is something that almost 99 percent of pro-lifers support.” This is surely true. And the statement suggests that DeSantis affirms pro-lifers’ conviction that fetuses have the rights of personhood and must therefore be protected on a nationwide basis.

If these stances put DeSantis on the right side of Evangelicals, however, it puts him on the wrong side of majority opinion. A 2022 poll from Florida Atlantic University found that a supermajority of Floridians believe that abortion should be legal in “all or most cases.” In Gallup’s most recent polling, “pro-choice” Americans outnumber “pro-life” ones by a 55 to 39 percent margin.

On the specific question of banning abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy, meanwhile, opposition to the pro-life position is overwhelming. A recent survey from PBS NewsHour suggests 65 percent of Americans — including 26 percent of Republicans — believe that abortion should be allowed during the first three months of pregnancy.

Abortion policy is one of the GOP’s greatest liabilities in 2024. Secular northern white voters were indispensable to Trump’s 2016 victories in the Rust Belt. And in 2022, Democrats did better in Michigan and Pennsylvania than they did nationally, in no small part because secular voters in those purple states feared new abortion restrictions. DeSantis has established himself as a more pro-life candidate than Trump. But in doing so, he has also undermined his claim to superior electability.

A similar trade-off confronts DeSantis on fiscal policy. According to the Times, DeSantis plans to “point out that as a member of Congress he voted against the trillion-dollar-plus spending bills that then-President Trump signed into law in 2017 and 2018.” To further bolster his fiscal conservative bona fides, DeSantis has not “ruled out trimming entitlement spending in ways that would affect younger Americans when they retire.”

Playing to small-government activists frustrated by Trump’s impiety on spending in general, and the imperative of slashing entitlements in particular, makes perfect sense for a challenger in need of a broader primary coalition. But cutting Medicare and Social Security is profoundly unpopular. And the GOP’s association with that ambition has long been one of its chief electoral liabilities.

Simply put, it is difficult to attack your opponent for being (1) too uneasy about banning abortion at six weeks and cutting Social Security benefits, and (2) too unelectable. The kind of Republican voter who is genuinely open to an electability argument is liable to be sufficiently clear-eyed and pragmatic to recognize the contradiction in DeSantis’s pitch.

The Florida governor has been a presidential candidate for scarcely more than 24 hours. The Iowa caucuses are nearly a year away. It is entirely possible that something will fundamentally shape the GOP primary’s dynamics in the interim. But for the moment, it is much easier to find reasons why DeSantis can’t beat Trump than reasons why he might.