The 2022 election was strange. Historically, the president’s party tends to suffer large losses in midterms, as its base grows complacent and swing voters indulge their fetish for divided government. And there was little reason to believe that last year would be an exception.

After all, last November, Joe Biden was a historically unpopular president presiding over exceptionally high inflation. Polls showed widespread disapproval of the Democratic administration in general and its economic management in particular. A “red wave” appeared to be cresting.

And yet that wave ebbed before it touched the nation’s most highly contested races: Even as Republicans won the two-party national vote for House control by a 51 to 49 percent margin in 2022, Democrats won 40 of the 64 races that were deemed very competitive by the Cook Political Report.

And in the closest Senate and gubernatorial races, the outcomes were even more odd. In the contests that Cook deemed either “toss-ups” or merely “leaning” toward one party, Democrats won 51 percent of the two-party vote — a higher share than they had secured in such races in 2020 — while claiming victories in 13 of 18 elections.

Altogether, this increased the Democratic Party’s power in the Senate and at the state level while leaving Republicans with a relatively meager nine-vote majority in the House. Had a few thousand more votes (in very specific places) shifted from Republicans to Democrats, Biden’s party would have retained full control of the federal government. As is, it still mounted one of the strongest midterm performances for an in-power party in modern American history.

By now, election analysts have produced plenty of compelling explanations for how this came to be. One is that the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade scrambled conventional midterm dynamics. Major policy changes often spur short-term electoral backlashes. This is one reason why the president’s party has often struggled in midterm elections, which frequently follow ambitious legislative sessions. But in 2022, even though a Democrat was in the White House, Republicans delivered the year’s most disruptive policy change. Thus, in purple states where abortion policy was a live issue, swing voters in general (and women in particular) gave Democrats unusually strong support.

Another explanation for the red ripple was Donald Trump’s singularly bad taste in general-election candidates. In various competitive Senate and gubernatorial races, Republican primary voters nominated MAGA extremists at Trump’s request. This predictably rendered the party less competitive.

But a new analysis from the Democratic-data firm Catalist points to another critical factor: the political ascendance of millennials and zoomers.

America’s youngest adult generations had been integral to the 2018 blue wave. Millennials saw their turnout rate surge from 22 percent in the 2014 midterm to 42 percent four years later. In 2018, the oldest zoomers became eligible to vote in a midterm for the first time. And they cast ballots at a higher rate than millennials or Gen-Xers had in their respective first midterms. Critically, zoomers and millennials collectively cast more than 60 percent of their votes for Democrats, helping the party win the national House vote by a landslide margin.

This was an ominous development for the GOP. Still, Republican operatives could comfort themselves with a pair of thoughts. First, while America’s rising generations might turn out in historically high numbers to rebuke President Trump, their participation was bound to fall sharply once politics grew more banal. And second, though millennials and zoomers were currently the least Republican generations that America had produced since Lincoln’s time, they would surely age into a more ordinary partisan distribution.

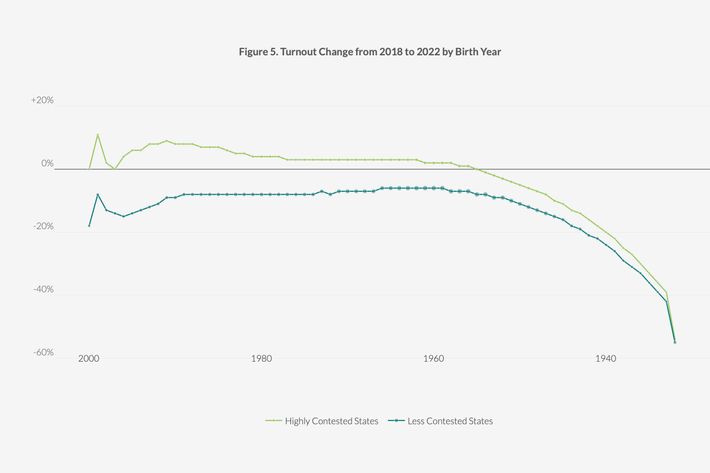

The 2022 results were not kind to such wishful thinking. As Catalist’s analysis of voter-file data reveals, millennial and Gen-Z voters collectively comprised 26 percent of the 2022 electorate, up from 23 percent in 2018. This was partly a function of aging. More zoomers were eligible to vote last year than in 2018. But turnout among eligible voters was also a factor. Nationally, millennials and zoomers turned out at a rate comparable to their historically high 2018 mark, and in highly contested races, the two generations actually voted at a higher rate than they had in such races in 2018.

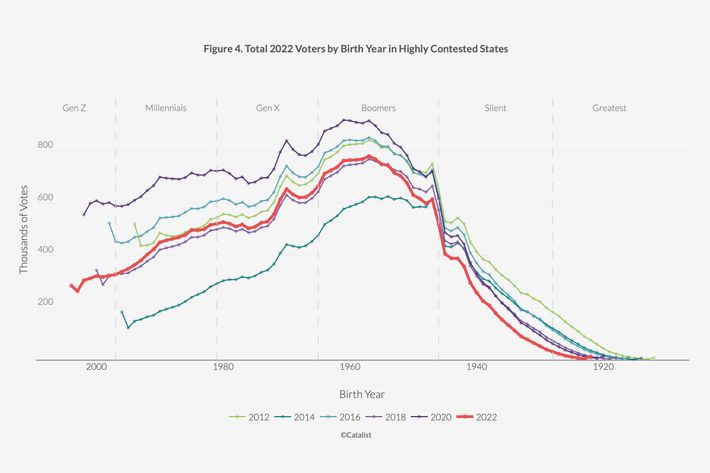

This is a big long-term problem for the Republican Party. With each passing election cycle, zoomers and millennials will become more likely to vote. As this chart from Catalist illustrates, generations tend to grow more and more electorally influential until they reach their mid-70s and then start aging out of the electorate owing to illness or death. Boomers have already passed their political peak. Millennials will be building toward theirs for a long time to come.

It is not surprising that millennials have retained their exceptionally strong Democratic lean even as they’ve exited their youth. Although cohorts do tend to grow a bit more conservative when (or if) they have children and buy a home, most voters’ political affiliations are cemented in adolescence and early adulthood, when myriad other aspects of their identities are forged. Millennials spent their formative years watching George W. Bush preside over catastrophic wars and an economic disaster while his party embraced soon-to-be-discredited social crusades (such as opposition to gay marriage). And millennials were also raised by parents who were markedly more socially liberal than the boomers’ forebears. It is therefore unsurprising that the generation has proven durably hostile to a Republican Party that refuses to abandon the cultural commitments of America’s white Evangelical minority.

The durability of birth cohorts’ political leanings means that generational churn by itself can remake our politics. There are many reasons why Barack Obama’s first midterm was a political disaster for the Democratic Party while Biden’s was a relative success. But one is that boomers constituted 69 percent of the electorate in 2010 but only 48 percent of it in 2022.

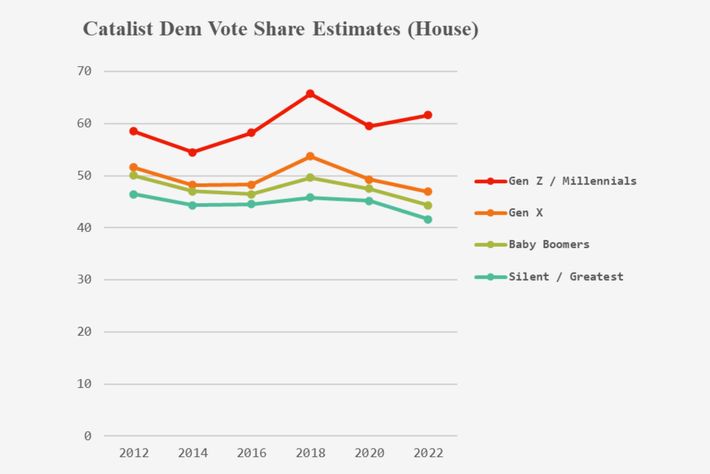

To this point, Republicans have managed to weather the rise of millennials and zoomers just fine. This is largely because America’s older generations have all shaded to the right since 2012. As a result, the political divide between millennials and zoomers on the one hand, and their elders on the other, has never been more stark:

Further, the GOP’s historically high support from non-college-educated white voters — combined with the overrepresentation of those voters in the Senate and Electoral College battlegrounds — has enabled the party to win power in excess of its popular support.

Both of these factors are likely to attenuate the GOP’s millennial problem in the near term. For one thing, Generation X is a right-leaning cohort that came of age during the Reagan recovery and is about to enter its prime voting years.

But Gen X is also a small generation. And the boomers are growing smaller with each passing year. If Republicans do not reconcile themselves to a more modern set of cultural values (and/or less plutocratic set of economic policies), generational churn will eventually make it very difficult for them to compete in national elections.

Here, three other quick takeaways from the Catalist report:

Women were critical to Democratic success. Female voters backed Democrats nationally at levels comparable to 2020, and in highly competitive Senate and gubernatorial elections, Democrats actually won a slightly higher share of women’s ballots than they had in similar races two years earlier (winning 57 percent, up from 55 percent in 2020). Resiliently strong support among white college-educated women helped to compensate for a sharp drop in Democratic voting among white college-educated men, who gave Democrats 51 percent of their votes in 2020 but only 44 percent two years later.

In competitive races, education polarization eased. Beyond America’s generational cleavage, a growing “diploma divide” between college-educated and working-class voters has been one of the defining dynamics of U.S. politics in recent years. This gap remains vast, but in 2022 it declined a bit from its Trump-era peak, particularly in competitive races. In such contests, Democrats gained four points of support among non-college-educated white voters, relative to 2020, while losing two points of support among college-educated ones.

Democrats’ performance with non-white voters was suboptimal in 2022. In last year’s midterm, Democrats lost seven points of support among both college-educated and non-college-educated Asian American and Pacific Islander voters relative to 2020. Their performance with Hispanic voters was largely unchanged from the Biden-Trump race with the party winning 62 percent of that demographic. In 2016 and 2012, however, the party had won upwards of 70 percent of Hispanic voters.

Black voters, meanwhile, remained overwhelmingly Democratic. But both their turnout rate and support for Democrats declined slightly from previous midterms. In 2018, Black voters represented 12 percent of the electorate; in 2022, they comprised 10 percent. In 2020, Black voters delivered 91 percent of their votes to Democrats — two years later, they gave just 88 percent of them to Biden’s party.