This will be the last student-loan-free summer. We’re now more than three years out since Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020 — a bill of such wide and indiscriminate stimulus that, in addition to its $2.2 trillion in cash and loans, suspended all student-debt payments. The $1.6 trillion in debt, of course, never really went away — but the longer the moratorium went on, the more abstract it became. Last August, President Biden proposed eliminating a $400 billion slice of federal student loans, which would zero out balances for 20 million Americans in a onetime forgiveness event, with the most aid going to Pell Grant borrowers. The plan was attacked as both “socialism” and a handout for elites, even though the vast majority of the benefits would go toward the poorest. In February, the Supreme Court heard a challenge to Biden’s plan, and it appeared skeptical. Even the most optimistic accounts concede that the Supreme Court can, and likely will, block Biden’s initiative. But in the meantime the president has kept pushing back the date when student-loan payments would resume.

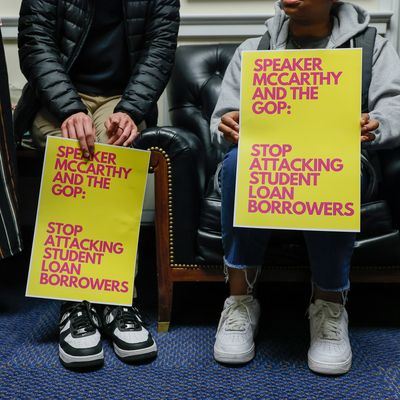

This week, student debt made its way into Washington’s consciousness again in the form of the budget deal. The text of the bill, which the Senate passed late Thursday night, ends the student-loan suspensions, meaning that — regardless of what happens with the Supreme Court — payments will be due again in September. This was part of the big compromise (that actually wasn’t much of one) between Biden and Speaker Kevin McCarthy, though it was an easy concession for the White House, which wasn’t widely expected to keep pushing the moratorium back. Regardless, this will restart a multitrillion-dollar machine at a time when the economy’s strength seems closer than ever to giving out.

There are about 45 million Americans who have student loans. Of those, the majority have $25,000 or less in outstanding debts, according to the Federal Reserve. That means for the last three years, most people were taking the $200 to $300 they would normally spend on paying off their student-loan debts and, instead, paid for the rest of their lives. All this money had to go somewhere. According to a study by the University of California, Irvine’s Student Loan Law Initiative, the pause improved most people’s financial standings, with credit scores increasing by about 30 points. This came from saving about $210 a month.

At some point, though, that extra savings starts to feel less like a cushion and more like just the money that you have. This would have been especially true during the past year, as price increases for food and gas spiked to a 41-year high. Already, credit-card delinquencies are at the highest level since about 2010 — a sure sign of financial stress. “There’s some concern now that, as those loan repayments restart at the end of August, you’re going to see higher delinquency rates on credit cards and other types of loans. That is one of the big concerns I think economists are paying close attention to,” Michael Jones, an economics professor at the University of Cincinnati, told me.

Still, all of a sudden, in about three months, something like a third of the country’s prime-age working population is going to see a big decrease —thousands of dollars — in their discretionary budgets, just as borrowing new money has become more expensive than at any point since 2008.

In a way, this is exactly what the Federal Reserve has been trying to do as it fights inflation — kill the demand that’s been baked into the economy for the last three years. When Fed chair Jerome Powell has held press conferences during the last few years, he’s rarely, if ever, had to answer questions about the impact of student debt on the economy. But he did in 2018, telling Congress that “as student loans continue to grow and become larger and larger, then it absolutely could hold back growth.” Adding student-loan payments is effectively a shadow rate increase, the kind of financial speed bump in the economy that could help slow down inflation by killing demand. According to a Goldman Sachs analysis, a resumption of student-loan payments would be the equivalent of a 0.2 percent drop in the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge. (It’s 0.1 percent if the Supreme Court lets Biden’s federal-debt wipeout stand.)

There’s an optimistic scenario in which kick-started student-loan bills help create a domino effect of virtuous scenarios: lower inflation, lower interest rates, more affordable stuff, everybody’s happy. In reality, it won’t be that simple. Still, the resumption of student loan payments is probably not going to be so bad. Ever since April 2020 — when the payments were first suspended — the purchasing power of the dollar has fallen by more than 18 percent. For most things, this sucks, since everything is more expensive. But inflation might as well be acid to loans: It dissolves the real value of the debt. And despite the Fed’s best efforts, the dollar is likely to decline further. By September, it will be three and a half years since the last obligatory student-loan payment — by then, the bills could seem even smaller.