The U.S. economy was supposed to be shrinking by now. Last fall, Bank of America predicted that America would be bleeding 175,000 jobs a month throughout the first quarter of this year. And the consensus outlook among investors, CEOs, and analysts was much the same: 2023 would be a year of recession, as rising interest rates choked off investment and consumer spending, forcing employers to slash payrolls.

But reports of the economy’s death have been greatly exaggerated. Last month, U.S. firms added 339,000 jobs. That’s a bigger monthly gain than the U.S. ever posted in 2019, a banner year for the American economy. Unemployment is still hovering around 3.5 percent, a half-century low. For the moment, labor market conditions are the opposite of recessionary.

And there’s little reason to think that this will change anytime soon.

When economic forecasters envision rising interest rates throwing the economy into recession, they typically picture the housing market cratering first. This is because housing is exceptionally sensitive to credit conditions. Home buyers generally take on mortgages to purchase their homes, and as mortgage rates soar, would-be buyers decide to stick with renting for a while longer. As demand cools, builders cut back on new developments, putting construction workers out of jobs. That in turn reduces the purchasing power of such workers, thereby slightly cooling demand for goods and services.

Indeed, when Forbes predicted in February that the U.S. economy was poised to rapidly weaken, it based this assessment on “a precipitous drop in housing permits.”

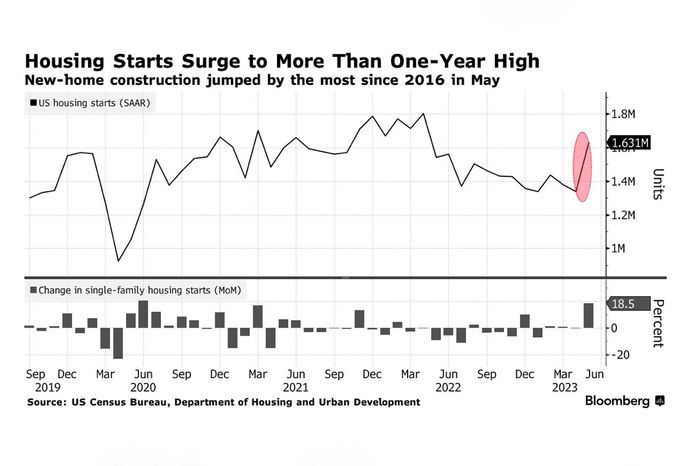

But this week, new data revealed that both permits and housing starts rebounded sharply in May with the latter posting the biggest monthly gain since 2016. New home construction jumped 21.7 percent last month to a 1.63 million-unit annualized rate, while multifamily housing starts grew by 27 percent. Permits, a proxy for future construction, rose by 5.2 percent.

Meanwhile, a survey released on Monday from the National Association of Home Builders showed housing-construction firms’ confidence rising for the sixth straight month.

What explains the housing market’s resilience amid the fastest rate increases in four decades? One contributing factor is that the cost of construction materials has declined as global supply chains have recovered from the pandemic. Another is that rising interest rates have, ironically, increased the impetus for new housing construction. There are many empty-nester households in the U.S. that, under the right conditions, would be inclined to sell their current homes and move into smaller ones, thereby increasing the total amount of floor space available on the market. But many such households are paying extremely low interest rates on their current homes and would have to accept a much higher rate, were they to buy a different house now. And the same basic dynamic holds for myriad other potential home sellers. So inventory on the resale market is thin, which means that only new construction can meet the demand for housing.

Of course, this raises the question of why housing demand has held up amid rising rates. One answer is that, in historical context, mortgage rates aren’t very high. While such rates have risen dramatically from the low levels that prevailed since the 2008 crash, they’re lower than they were throughout the 1980s and 1990s, when plenty of Americans were perfectly willing to purchase houses.

A second answer is that many consumers can afford to weather rising costs, thanks to the strong jobs market and to the savings they accrued during the pandemic. True, years of inflation have eroded Americans’ COVID-era savings. But in recent months, price growth has slowed while wage growth has persisted. As a result, between May 2022 and May 2023, real wages — wages adjusted for inflation — increased by 0.2 percent.

All this still leaves us with the mystery of why the labor market has held up so well, even as the Fed has discouraged investment and consumer spending by raising the cost of credit. Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, argues that several idiosyncratic features of the post-COVID economy explain its durable strength. One such feature is that businesses have become more reluctant to cut costs by shedding workers. The experience of slashing payrolls during the pandemic, then struggling to rapidly restaff, taught many companies that the costs of recruiting and onboarding workers are high. This revelation, combined with baby-boomer retirements shrinking the labor pool, has rendered firms more inclined to hold onto workers, even when the present level of demand renders them somewhat superfluous. And when employers refrain from slashing jobs in response to dipping demand, that prevents a dip in consumer spending from turning into a plunge.

After all, in a normal recessionary cycle, a drop in demand leads to layoffs, which leaves workers with less purchasing power, which leads to a bigger drop in demand, which leads to more layoffs.

A second factor is that households and businesses have much lower debt levels than they did before the 2008 crash. Households now dedicate a historically low share of their income to interest and principal payments. This lack of reliance on debt mitigates the impact of interest-rate hikes while rendering consumers more financially resilient in the face of rising prices.

A third factor is the moderation of global oil prices. Energy is an input into virtually all goods and services. And although the U.S. economy is less reliant on oil than in earlier epochs, the price of crude still exerts a big impact on macroeconomic conditions. Oil prices have fallen considerably from the highs they hit during the first months of the Russia-Ukraine War.

If a 2023 recession now looks unlikely, a “soft landing” from the heights of post-COVID inflation remains far from assured. There are some signs of economic cooling. Consumer spending is lower today than it was one year ago. Business investment in equipment is falling. Foreign demand for U.S. exports, meanwhile, is weak and getting weaker, as China and much of Europe teeter on the brink of recession.

The biggest threat facing the U.S. economy, however, may be one of our government’s own design. Right now, it looks plausible that the U.S. can enjoy slowing inflation and a strong labor market simultaneously. Indeed, core inflation has fallen by more than a percentage point since September, even as unemployment has remained near historic lows. Currently, consumers are slowing their spending without pulling back completely, as the savings rate rises. A “soft landing” scenario, in which inflation normalizes without a recession, looks increasingly possible.

A swift return to 2 percent inflation, however, looks much less likely in the absence of a recession. If the Federal Reserve decides that a very gradual reduction in inflation is not sufficient and continues to raise rates at a rapid pace, then eventually high credit costs are liable to bite.

At present, the case for tolerating somewhat elevated inflation for the sake of avoiding a recession seems strong. The argument for policymakers to induce higher unemployment, rather than tolerate persistent price growth, has always hinged on the notion that failure to do so would bring steadily worsening inflation. The mechanisms by which inflation becomes self-accelerating are (at least) twofold: One is that rising prices will lead workers to demand higher wages, which will lead firms to raise prices in a vicious cycle. Another is that, as consumers realize that goods will be much more expensive a month from now than they are today, they will all increase their present-day spending en masse, thereby bidding up prices even higher, leading consumers to increase their panic purchasing even more.

But there is little sign that either of these dynamics are surfacing in today’s economy. Nominal wage growth has slowed in recent months along with inflation. And inflation expectations remain anchored, which is to say consumers do not believe that price growth is going to rapidly accelerate.

So long as there is no sign of accelerating inflation and price growth is slowing, there is little reason to risk a recession for the sake of reducing price pressures more rapidly. This is especially true when one considers the perverse consequences that drastically higher rates would have for housing affordability. The leading source of services inflation today is shelter costs. To the extent that rising rates succeed in cooling the labor market by inducing a recession in the construction sector, they will only exacerbate future shelter costs, since the best way to durably reduce such costs is through an expansion in the housing supply.

Today, jobs are abundant, real wages are (modestly) rising, and prices are stabilizing. Policymakers should see this economy as a success worth preserving, not a crisis that must be resolved at the risk of higher unemployment.