When South Carolina teacher Mary Wood assigned Ta-Nehisi Coates’s 2015 memoir, Between the World and Me, to her AP Language Arts students last spring, it was as part of a unit on the argumentative essay. She would soon learn that a few students were uninterested in what she — and Coates — sought to impart. After she played two videos on systemic racism to prepare students for the book, some complained to their local school board. “Hearing (Wood’s) opinion and watching these videos made me feel uncomfortable,” one student wrote, as reported by The State. “I actually felt ashamed to be Caucasian … These videos portrayed an inaccurate description of life from past centuries that she is trying to resurface. I don’t feel as though it is right because these videos showed antiquated history. I understand in AP Lang, we are learning to develop an argument and have evidence to support it, yet this topic is too heavy to discuss.”

Another student wrote that they were in “shock” that Wood “would do something illegal like that,” and added, “I am pretty sure a teacher talking about systemic racism is illegal in South Carolina.” Indeed, legislators had recently added “a proviso” to the state budget forbidding the use of state money to teach that “an individual, by virtue of his race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist or oppressive” and that “an individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his race or sex,” as The State explained. Wood’s school district halted the lesson.

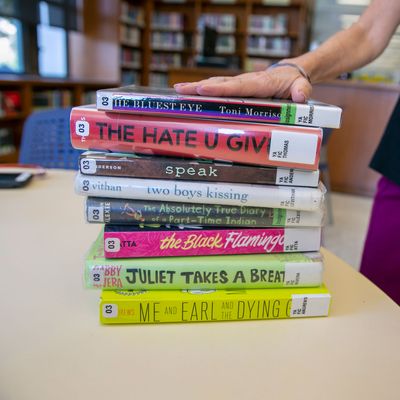

Groups like Moms for Liberty have earned national infamy for their book-banning campaigns. Yet censorship demands are widespread, encompassing legislators and, in Wood’s case, students. They all dream of the same world, a place without progress or challenge.

The purpose of an AP course is to introduce high-school students to college-level ideas. There’s an assumption of intellectual maturity, which Wood herself noted in a letter to the school district. A description for her course says the “best response to controversial language or ideas in a text might well be a question about the larger meaning, purpose, or overall effect of the language or idea in context.” Students must engage the text, even if they ultimately disagree with the positions an author takes. This is basic academic work, assigned to prepare students for college and for life in the broader public sphere. The students who complained sought to exempt themselves morally from any complicity in systemic racism; at the same time, they desired a reduced intellectual load. As one put it, “This topic is too heavy to discuss.” And school-district officials and state legislators agree.

A few hundred miles north in Hanover County, Virginia, the school board voted on Tuesday to ban 17 books from school libraries. Over in Nixa, Missouri, school-district officials may soon ban the graphic novel Maus after employees flagged it for having sexually explicit content. As author Art Spiegelman recently told the Washington Post’s Greg Sargent, there is nudity, but it’s not sexual. The art depicts his mother, dead by suicide, in a bathtub. “She was sitting in a pool of blood when my father found her,” he told Sargent, which is a “rather unsexy image seen from above” and “not something I think anybody could describe as a nude woman. She’s a naked corpse.” Spiegelman doesn’t believe that officials really object to the nudity. “It was the other things making them uncomfortable, like genocide,” he said. “I just tried to make them clean and understandable, which is the purpose of storytelling with pictures.”

Discomfort is a natural part of the educational process. In a healthy democracy, perhaps, no topic would be too heavy to discuss. Public schools are ideally places of learning, where students aren’t just supported but challenged as they mature into citizens. A rising authoritarian impulse would deny them that intellectual evolution. (Pundit furor over the left’s “cancel culture” missed the real threat creeping in from the right. Though leftist overreach isn’t entirely imaginary, it has nothing on the right’s long history of book-banning, and its growing anti-intellectualism has been plain to see for some time.) By shielding students from so-called “controversial” ideas, censors would raise a generation of perpetual children. Those efforts, of course, are not guaranteed to succeed. Children may be malleable, but they aren’t robots who can be programmed to perform a specific routine. Nevertheless, the right-wing push to hide inconvenient realities from students could have real and lasting consequences. Without an education, it may be difficult to discern truth from fiction. Propaganda can thrive and obscure facts like the reality of systemic racism.

That is what the censors want. The spirit that halted Wood’s lesson in South Carolina and that may remove Maus from schools in Missouri betrays a fundamentally conservative and anti-intellectual impulse. To oppose progress for minority groups — or to insist such progress has already occurred, when in fact it is still in motion or, as with LGBT rights, subject to backlash — requires a deliberate form of ignorance. Though right-wing grifters have financial incentives to pretend that the facts aren’t what they are, others might find it difficult to sustain their ignorance in the face of evidence. So the right seeks to erase reality where it can. It derives comfort from falsehoods. The world it seeks is a narrow one devoid of complexity. We must demand better, while we still can.