If the government tightly limited the production of sneakers, thereby triggering a bidding war over scarce athletic footwear, few would question whether the state’s deliberate suppression of shoe manufacturing was implicated in rising sneaker prices. In the shoe market, people find it intuitive that limiting the supply of a widely sought good increases its price.

And this same intuition holds for most other markets. If a drought decimated wheat harvests, leading to a shortage of grain and rising bread prices, few would have trouble discerning that the latter was a consequence of the former.

But in housing, this comprehension of the relationship between supply and affordability breaks down. A 2022 study from political scientists in the University of California system found that a majority of Americans do not believe that increasing the supply of housing makes it more affordable. And this perception was not unique to homeowners, who have a material interest in maintaining housing scarcity, but also prevailed among renters, who bear the brunt of America’s housing shortage. The researchers presented survey respondents with a wide array of different question wordings and arguments, and still only between 30 and 40 percent agreed that increasing the supply of housing units would improve affordability.

This widespread confusion is understandable. If you see a lot of new housing being built in your area, you wouldn’t necessarily be wrong to prepare for a rent hike. But the reason why new construction sometimes correlates with rising rents is not that housing is a good unlike any other, such that the more of it you create the more expensive it becomes.

Rather, the reason is that developers build new housing in response to rising demand. When a bunch of tech firms open up headquarters in Austin and create lots of high-paying jobs there, more high-skill workers will move into the city to take those jobs. Those workers will demand housing, and developers will respond by increasing construction.

But you can’t stop the yuppies from coming by blocking that construction. So long as high-paying jobs are being created in your city, high-income workers are going to move there. If there is no new “luxury” housing to absorb them, they will simply outbid less affluent residents for the housing units that already exist. Thus the less new housing that gets built, the faster rents will rise in a booming city.

And yet owing to the myriad restrictions on housing development in most U.S. cities, supply-chain bottlenecks, and other factors, new housing construction often fails to ramp up fast enough in response to rising demand to reduce rents; in such cases, it merely slows the pace of rent increases. Therefore, if you see new housing being built in your neighborhood, you have some cause for expecting a rent hike when your lease is up.

If new construction sometimes augurs rent increases, however, it does not cause them. Evacuations often precede hurricanes. So if you live in a seaside town and see your neighbors all packing up their things and leaving at once, that’s a decent indication that a hurricane is coming. But it would not be rational to respond to this observation by imploring your neighbors to stay put lest they cause wind speeds to surge above 75 mph.

To be sure, believing that new housing construction can trigger rent increases is not as irrational as thinking that evacuations cause hurricanes. There is a coherent theory of how the former could occur: Shiny condo towers attract higher-income people into a neighborhood, which leads to the opening of stores that cater to upscale tastes, which attracts more high-income people into the neighborhood, which pushes up demand for housing there and, thus, rents. In practice, though, there are a good number of studies showing that this “induced demand” phenomenon does not actually happen, even at the hyperlocal level.

At the level of a city as a whole, meanwhile, there is no ambiguity in the empirical literature: More housing leads to more affordability. People will not move to a new city just because they heard that there’s a condo tower there with a sick roof deck. It is plausible that, in some circumstances, affluent people already living in a city might move to a new neighborhood because its housing stock has become more desirable. But to the extent that this happens, it would have the effect of reducing demand for housing in other parts of the city. As a result, there is overwhelming empirical evidence that expansions in housing supply slows rent growth at the municipal and regional levels.

In fact, Americans are seeing the power of new housing construction to push down rents right now.

Between 2020 and 2022, America witnessed a huge run-up in rental prices. This spike in housing prices was long in the making. Over the past decade, Americans formed 15.6 million new households but built only 11.9 million new housing units. As the millennial generation aged out of living with roommates (or parents), demand for housing was always poised to surge far past supply in the early years of this decade.

But the pandemic exacerbated matters. The rise of remote work abruptly increased Americans’ demand for floorspace. Many laptop workers who’d previously been comfortable living with roommates decided they needed their own one-bedroom apartment; many of those in one-bedrooms decided they needed a two-bedroom apartment to accommodate a home office; many with a two-bedroom decided they needed a house, etc. Meanwhile, as remote workers trickled out of urban centers into suburbs, beach towns, and other amenity-rich (but previously somewhat job-poor) areas, rents in those places suddenly surged.

But now, rent growth has returned to its pre-pandemic norm with prices advancing at an annual pace of between one and 3 percent, according to real-estate data firm CoStar Group. In June 2023, asking rents were just 1.1 percent higher than they had been 12 months before. Given that wages grew at a far faster clip over that same period, a rental home was more affordable for the typical worker this June than it had been a year earlier.

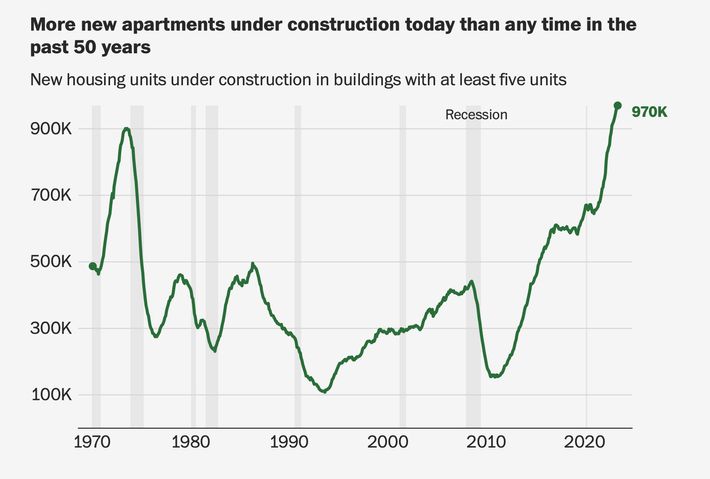

What explains this deceleration in rental prices? As with any economic development, more than one factor is at play. But the biggest one by far is that developers responded to surging demand by building more housing, which is now coming onto the market. As the Washington Post reports, nearly 1 million new apartment units are under construction right now. More than 500,000 of those units will be available for rent this year, while the rest will follow in 2024.

But housing isn’t being built at the same clip in all parts of the country. Some cities have more permissive zoning codes than others. And in Sun Belt metros, where there is abundant cheap land ringing the urban center, it is relatively easy and affordable to expand the housing stock through suburban sprawl.

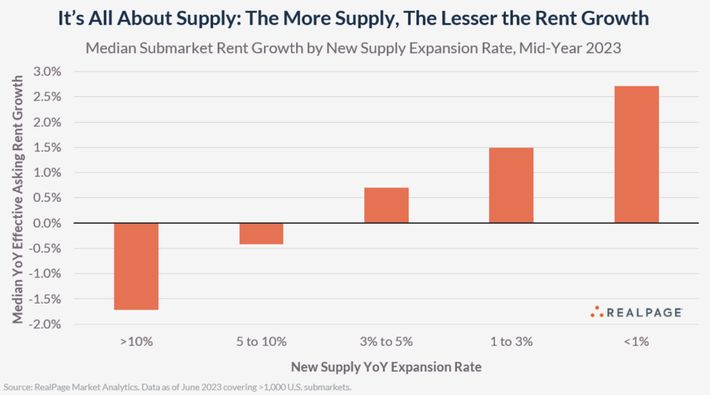

As housing economist Jay Parsons documents, where developers have built a lot of housing in recent years, rents have actually fallen. Where they’ve built little housing, by contrast, rent growth has continued to accelerate:

Although rent growth is slowing, asking prices in most of the country still remain far above their pre-pandemic level. Which means that, even in some areas where there’s been a considerable increase in housing construction, shelter is still much less affordable for many residents than it used to be.

But this does not mean that facilitating the construction of market-rate housing will not help such residents. As Parsons data illustrates, their rents would be even higher today were it not for the recent expansion in market-rate housing. And we don’t yet know how much scope there is to increase affordability through zoning reform, since America’s building codes remain extremely restrictive. It is still illegal to erect an apartment building on roughly 75 percent of our nation’s residential land. If we fully legalized the construction of multifamily housing, supply would plausibly increase so drastically that nationwide rents would fall, rather than merely slowing their growth. The fact that we’ve seen such deflation in areas with a greater than 10 percent annual increase in housing supply lends credence to this notion.

Relatedly, there is a popular idea that new market-rate housing can’t reduce rents for working people because private developers prefer to build “luxury” properties instead of affordable ones. But this view is largely misguided. It’s true that apartment buildings without rooftop swimming pools, doormen, or high-end appliances are cheaper to build and maintain than those that do feature such amenities. But the primary reason why newly built apartments in high-demand cities are expensive is because they sit on highly valuable land. A 500-square-foot apartment in Williamsburg with a tiny bedroom and microscopic kitchen would not qualify as “luxurious” if one plopped it down in Lansing, Michigan.

To a large extent, the designation “luxury apartment” is just a propaganda term used by the real-estate industry. Any new building is going to have some desirable aspects merely by virtue of being recently constructed (i.e., it won’t have decades-old appliances or antiquated heating and cooling systems). In a hot market, that fact alone will render newly built housing unaffordable to working-class people, even if it doesn’t come paired with a fancy roof deck or other signifiers of luxury. But new buildings will absorb high-income renters, reducing demand (and thus rental prices) for older housing units.

All of this said, it is absolutely true that we can’t achieve universal housing affordability through zoning reform alone. The market will never provide sufficient housing for low-income people because it is not profitable to do so. But the government can convert “luxury” housing into “affordable housing” merely by providing rental subsidies to non-affluent people who wish to live in such buildings. And the state can also help promote the construction of more new housing by providing low-cost financing to developers who agree to set aside a certain number of new units for subsidized renters.

We can’t fully resolve our housing crisis by unshackling the invisible hand. But widespread skepticism about the relevance of “supply and demand” to the housing market is making the crisis worse. You can’t make shoes cheaper by making them harder to produce. Hopefully, cities with restrictive zoning laws and persistently high rent growth will eventually realize that the same is true of homes.