Donald Trump has an excellent chance of being the U.S. president come 2025. Or so current polls suggest, anyway.

As of this writing, the former insurrectionist-in-chief leads Joe Biden by about half a percentage point in RealClearPolitics’s polling average. In 2020, the decisive state in the Electoral College — Wisconsin — was nearly four percentage points more Republican than the nation as a whole. Had Biden won the national popular vote by “only” three points that year, Trump likely would have won reelection.

There’s reason to think that the GOP’s advantage in the Electoral College has narrowed since 2020. The end of Roe v. Wade seemed to nudge secular whites in the Midwest back toward blue America. But even if one makes the questionable assumption that the 2022 midterms and current polling provide a preview of regional voting patterns next year, the GOP would still have a roughly 0.7-percentage-point Electoral College advantage, according to the New York Times’ Nate Cohn.

This implies that a tie (in the national popular vote) goes to the Trumpers.

Of course, hypothetical general-election polls more than a year before Election Day should be taken with several tablespoons of salt. And it is not hard to construct a case for Democratic optimism.

After all, it’s plausible that Trump’s ceiling of support is lower than Biden’s. Sure, red America’s favorite scoundrel might be leading Biden by 45.2 to 44.8 percent in RCP’s average. But when the election gets closer and undecided voters are forced to make a choice, they will break overwhelmingly for the less luridly loathsome candidate. Meanwhile, Trump’s myriad legal woes are likely to erode his political standing over the course of the campaign.

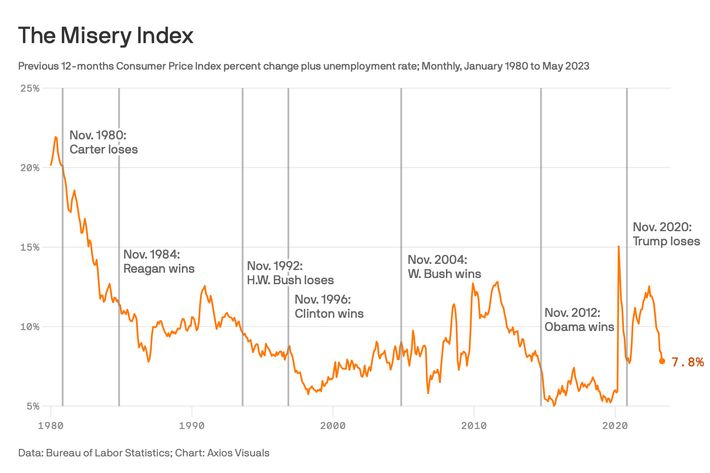

The linchpin of the case for Democratic optimism, however, is the assumption that public sentiment about the economy will only improve between now and November 2024. By all appearances, widespread antipathy for inflation and other forms of post-pandemic economic dysfunction has weighed on Biden’s approval ratings over the past two years. But in recent months, price growth has slowed while employment has remained high. The so-called misery index — the unemployment rate combined with the inflation rate — is now at a lower level than it had reached during the reelections of Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama.

Voters might still be grousing about the price level at the moment. But if real incomes continue to rise, by November 2024 they’ll realize that Biden has actually led the U.S. economy out of mass unemployment and into a boom time.

It’s unclear precisely how much of the public’s displeasure with the economy reflects objective material conditions and how much derives from media coverage or a diffuse discontent with post-pandemic life. Americans tend to express positive assessments of their personal circumstances even as they disdain economic conditions more generally. Regardless, a sustained growth in real income certainly couldn’t hurt Biden’s prospects for victory.

And there’s some basis for bullishness about the U.S. economy in 2024. This month, Goldman Sachs lowered its odds of a recession within the next year to 15 percent. That analysis is buttressed by trends in both inflation and GDP growth. The Core Personal Consumption Expenditures index — the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge — has been rising at a roughly 2.2 percent annualized rate over the past three months, not far off the central bank’s target. At the same time, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracker is estimating 5 percent economic growth for the third quarter of this year. That’s above consensus estimates, which nevertheless point to the economy growing at a healthy 3 percent clip.

The fact that prices have managed to moderate — even as growth has remained robust — suggests that the Fed might not need to keep suppressing demand through interest-rate hikes in order to dampen inflation. As the COVID emergency recedes further into the past, it is possible that improvements in the global economy’s productive capacity have rendered it capable of supporting a higher level of demand at stable prices. If this is so, then 2024 might witness falling interest rates, steady growth, and cooling inflation, a recipe for a brighter national mood.

All of this said, it remains plausible that the economy might trend in the opposite direction. Although Goldman Sachs has slashed its probability estimate for a 2024 recession, the consensus view in Bloomberg’s survey of economists is that the U.S. faces a 60 percent chance of entering a downturn within the next 12 months.

Here, three risk factors that threaten to undermine the U.S. economy — and thus Biden’s reelection prospects — next year:

1. Oil prices could rise and then remain elevated.

Although the overall outlook on inflation has been encouraging in recent weeks, energy costs have been surging. With Saudi Arabia and Russia throttling supply during the summer, oil prices have shot up by nearly 30 percent since June. If a barrel of oil remains near the $100 mark for an extended period, preventing the economy from tipping over into either higher inflation or a recession could prove challenging.

Since energy is a key input into virtually every good, high energy costs can bleed into the prices of other consumer items. On the other hand, high energy costs can also reduce economic demand by eroding consumers’ purchasing power (if your gasoline bill goes up by 50 percent, your spending on discretionary items might fall by a similar figure). High oil prices therefore put the Federal Reserve in a bind. A sustained spike in headline inflation might make the central bank feel politically obligated to raise rates, even as doing so might exacerbate a decline in consumer buying power, thereby increasing the odds of a recession. Notably, soaring oil prices helped drive America’s recession in the mid-1970s and arguably contributed to downturns in both of the following decades as well.

It is possible that the Saudis and Russians will ramp production back up early next year. But as Bloomberg notes, even if they do, it will take a while to refill oil inventories, during which time the global energy economy will be vulnerable to shocks. For its part, the United States doesn’t have much bandwidth to ease the crisis as its Strategic Petroleum Reserve remains heavily depleted from last year’s releases.

2. Americans might suddenly start feeling the pain of the Fed’s rapid interest-rate hikes.

To this point, the Federal Reserve’s historically rapid interest-rate hikes have had far less impact on consumer spending and employment than either the policy’s champions or critics had predicted.

One interpretation of this development is that the economy is less sensitive to interest rates than many had previously believed. But another read is that it takes a while for the pain of higher rates to make itself felt.

In 2020 and 2021, many households and companies refinanced their debts at historically low interest rates. Securing low-cost capital during that period insulated consumers and businesses against the burden of rate hikes this past year. But as the months pass, more and more borrowers will be rolling over debts at much higher interest rates. Higher capital costs could in turn depress profits, leading companies to lay off employees. Households, meanwhile, might be forced to cut back on spending as their debt burdens rise. Already, credit-card delinquencies are rising.

3. Consumer spending could drop precipitously as households’ reserves are exhausted.

Interest rates aren’t the only headwind facing consumer spending in 2024. With the aid of stimulus checks, households built up extraordinarily high cash balances during the pandemic. And such savings helped consumers weather a sustained period of falling real wages. But they’re now poised to burn through those excessive savings by the end of this quarter, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

At the same time, the resumption of student-loan payments will cut the discretionary incomes of tens of millions of households. With wage growth slowing, gains in labor income might not be sufficient to counteract declining savings and rising debt obligations.

And demand could be further depressed by a decline in government spending. As Morgan Stanley notes, the CHIPS and Science Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act are heavily front-loaded in their investments. Therefore, the economic benefits of such fiscal spending might recede in 2024, even as many state and local governments are also tightening their belts. The less money that governments inject into the economy, the less makes its way onto households’ balance sheets.

None of this necessarily means that a recession is more likely than a soft landing from inflation (which is to say a circumstance in which price growth returns to 2 percent without any substantial increase in unemployment). But an election-year downturn remains plausible. Given that Biden is currently running neck and neck with Trump amid objectively solid economic conditions, this fact is disconcerting.