The sensation had, perhaps, dulled. In these six years since the convulsive revelations of Me Too, there have been counterrevolutions, something of a return to the old doubts and suspicions, enough collective shrugging to think the whole thing was over, or at least that the true monsters had been punished and the world could move on.

Then came New York’s Adult Survivors Act, which has this year made clear just how many shocking accounts of abuse and institutional complicity were still untold long after Me Too was declared dead. Passed in 2022, its year-long “lookback window” temporarily lifted the statute of limitations on filing civil suits for sexual abuse; it expired the day after this past Thanksgiving. The law was modeled after the Child Victims Act, a pre–Me Too proposal that had long languished thanks to powerful opposition by the likes of insurance companies and the Catholic Church, but which passed overwhelmingly in a Democratic-controlled legislature in 2019. A criminal look-back window for both laws was off the table for constitutional reasons.

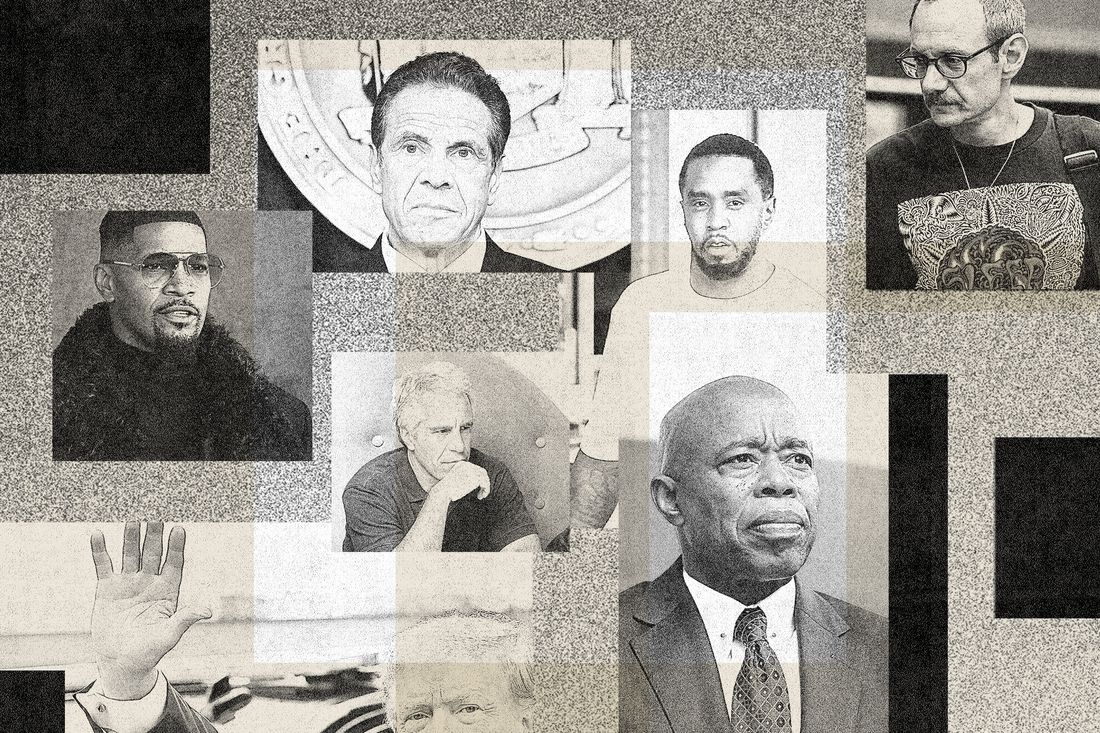

The year-long window brought suits against some known quantities, such as Donald Trump, already in court for defaming E. Jean Carroll after she said he raped her and quickly sued for the act itself. Jeffrey Epstein wasn’t alive to be sued, but his estate was, and Deutsche Bank and J.P. Morgan agreed to multimillion-dollar settlements after being sued under the act. Brittany Commisso — who filed a criminal complaint against her former boss, then-governor Andrew Cuomo, that led to no charges despite prosecutors calling her “cooperative and credible” — sued for the chance to see him in civil court.

But the days before the November deadline brought an avalanche of lawsuits that showed that there are still fresh (alleged) horrors to learn: Cassie Ventura’s gruesome account of abuse at the hands of Sean Combs, settled out of court within a day; the allegations from a woman that New York mayor Eric Adams sexually assaulted her in 1993. In 2022, State Senator Kevin Parker voted for the Adult Survivors Act. In November, a woman sued Parker under the law, saying he had raped her after a relief trip to Haiti in 2004. (They all deny the charges.) In the end, about 3,000 suits were filed. In a conversation that has been lightly edited for clarity, State Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal, who represents parts of western Manhattan, talks about what surprised him about the year of retroactivity and the chances of extending it.

What did it take to pass the Adult Survivors Act?

There was some belief before the Child Victims Act that statute of limitations were sacrosanct; that they couldn’t and shouldn’t be touched. So there was an educational curve that we had to overcome, and the Child Victims Act really proved that point.

Marci Hamilton, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, helped us write this bill. She’s been leading an organization called Child USA that has raised awareness around the unfairness that exists for sexual-abuse survivors and state statutes of limitation that have been extremely narrow and have prohibited a lot of cases to be filed and justice to be pursued. Not to mention the public-safety component — that’s something she talks about a lot, but I agree it’s important — that every time one of these cases is brought, it potentially alerts authorities and others who may want to take steps to consider whether an individual is still in contact with potential victims.

How much did the advocacy around Me Too matter to these two laws?

I would argue that the awareness around sexual abuse propelled it forward in the legislature.

In 2019, before the Adult Survivors Act passed, you said you thought that unlike the Child Victims Act, people would be more likely to bring cases against individual offenders and less institutions like the Catholic Church or the Boy Scouts. And of course there are these very famous people who are named in these suits. But it was really striking that it’s something like one in six of them involve Rikers-related allegations.

I didn’t anticipate hundreds of cases being filed against the Department of Corrections. I didn’t see that one coming. Nor did I realize that there’d be Robert Hadden and other physicians who have violated the trust of so many of their patients. So the institutional context, at least in the medical profession and in our corrections system, was surprising to me. I was gobsmacked by those revelations.

The public sometimes has trouble understanding civil lawsuits asking for money damages, or they see it cynically. In your view, what kind of justice is it to file a lawsuit like this? What does it offer a victim or a survivor to ask for money?

It’s an important point. And this is not about guilt; it’s about liability. But for the survivor, those can amount to the same thing in terms of having their story heard in a courtroom with a judge and a jury and a finding that would confirm their suffering. That’s what I understand to be the biggest breakthrough for many of these survivors, is to be heard for the first time on this issue. And that’s obviously a painful experience for them and why it takes a long time for individuals to process the reality of what happened to them. Again, another reason why we may want to make these windows permanent or extend them further.

I wonder if there are also just people who are not comfortable with criminal prosecution for their perpetrators.

It’s possible. A victim has to pay for an attorney to bring a civil suit. And if you do find an attorney, they generally are looking for deep pockets. So that’s a limiting factor in who can file these suits. Most sexual abuse, whether the victim is a child or an adult, that happens among family members. But if you’re suing your uncle, you’re probably not going to have the interest that you would if you’re suing an entertainer or a well-known politician. So it’s painful to consider the fact that the most likely setting for sexual abuse is in the family, but there’s very little opportunity for the average New Yorker to find a venue to have their claims served.

That’s a very good point, because I see that a lot of the lawsuits against institutions that you mentioned have a lot of plaintiffs. So that obviously makes it more worthwhile for these law firms. And it seems as though only a few law firms are specializing in bringing these kinds of claims.

It’s a cottage industry. I welcome it. But I think it points to the need for greater government support for civil legal services, for example, but currently there isn’t that type of funding to file these types of lawsuits.

What else surprised you? What else struck you?

Well, the notoriety of a number of those named in lawsuits was surprising. Colleagues, current and former, in Albany. The 45th president of the United States, among others. The flurry of cases at the end, I think, suggests the potential reality that some people didn’t file in time. It’s been hard to get the word out. Certainly a case against Diddy rose to the top of people’s social-media feed, but that was a late filing. And I do wonder if everyone who needed to heard about the opportunity in time.

Advocates are calling for an extension of the look-back window. Is that something you support?

I support, if not a permanent window, another temporary one. You have to ask the question, Who benefits from statutes of limitations? And we’ve seen that the courts have been able to sift through evidence. There haven’t been, to my knowledge, any frivolous cases that have been confirmed. And that would also apply to the child victims. Maryland has made a permanent window. Other jurisdictions are looking at that approach. I think it’s put a lot of powerful people and institutions on notice. I think maybe some breathed a heavy sigh of relief by November 25 when they weren’t the subject of a claim. But I don’t think they’re necessarily out of the woods, given what I see among advocates and having spoken to colleagues who are interested in revisiting it.