Ever since he was a boy, Bill Ackman dreamed of becoming a businessman. He sold ads for Let’s Go travel guides from his dorm room as an undergrad at Harvard and co-captained the business-school crew team, which had oars decorated with dollar signs. “Let’s face up to what Harvard Business School represents,” Ackman wrote in the school newspaper after the rowers were booed at the Head of the Charles. “We spend 90 percent of our studies at HBS pursuing the maximization of the dollar.”

But even as a college student, Ackman was also thinking about how the university worked — and the role it played in society. He majored in social studies and took a formative course on ethnicity and nationalism taught by Marty Peretz, who became a lifelong mentor. “He’s a bruiser,” Peretz told me recently when I asked what had impressed him about Ackman. “A bruiser and a brain do not very often go together.” Ackman’s senior thesis, submitted in 1988, looked at how admissions quotas to limit the Jewish student population in the 1920s echoed what some saw as the unfair treatment of Asian Americans in the ’80s. Ackman concluded that Harvard was admitting more students from other minority groups simply because “it has been pressured to do so.” He also critiqued the idea that the university was primarily a place for the transfer of knowledge. The real purpose of a university, in a capitalist society, was “to distribute privilege,” Ackman wrote. “The question, ‘Who should go to college?’ should perhaps more appropriately become ‘Who is going to manage society?’”

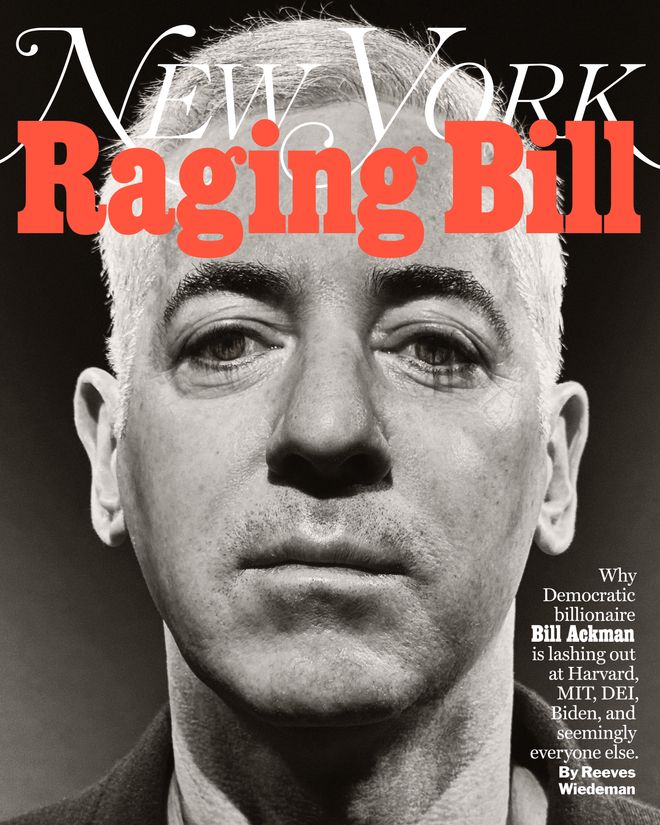

Cover Story

Ackman left Cambridge to join the managerial class — he started a hedge fund and became a billionaire — and didn’t spend too much time thinking about his alma mater. He gave a little money in the ’90s, earmarked for Holocaust studies. In 2014, he funded a center for behavioral economics with a professorship in his name and tossed $5 million to the crew team. His nephew enrolled at Harvard, as did his eldest daughter — which, Ackman told me recently, is where the trouble started.

“She became, like, an anti-capitalist. Like practically a Marxist,” Ackman said in January, leaning across a large conference-room table at the offices of his hedge fund, Pershing Square. “We’d talk about capitalism, and she would freak out at the table.” His daughter was in the social-studies department just like her father, and rowed crew, too, but she had chosen to write her thesis on “The Concept of Reification in Western Marxist Thought,” having come to very different conclusions than her father had about how the world should work. Ackman said it felt as though she “had been indoctrinated” into a cult. Father and daughter eventually made up — he bought her a copy of Das Kapital as a present for her graduation in 2020 — but in hindsight, Ackman saw it as an early warning. “That was an indicator, but I didn’t know if that was just my daughter or what,” he said. “I didn’t think, like, the biology department was involved.”

Ackman was talking to me several months deep into a war that had started with his objection to a controversial student letter about Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel, before blossoming into a much broader assault: on the state of higher education; the Democratic Party Establishment; diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives writ large; and — well, new targets seem to appear with each passing week. He was among the loudest voices pushing to oust Harvard’s first Black president, Claudine Gay, after concerns about her handling of campus divisions around the Israel-Hamas war snowballed into questions about plagiarism in her academic work. By January, Ackman’s second wife, the glamorous and slightly uncategorizable scientist-architect Neri Oxman, was being accused of plagiarism, too, and Ackman was promising to not only sue Business Insider, which published the allegations, but to use artificial intelligence to audit the work of other college professors as an act of spousal vengeance. The drama was playing out live on X, where Ackman has been posting daily to his 1.2 million followers, sometimes going on for thousands of words and with such a manic persistence — “I am posting while on the elliptical for better time management” — that the Financial Times published a quiz testing readers’ ability to tell the difference between Ackman’s tweeting and Patrick Bateman’s unhinged inner monologue from American Psycho. “I took the quiz,” Ackman told me. “And I got a perfect score.”

When we met, Ackman, who is 57, wore navy Allbirds and a Bremont watch that glowed whenever he pulled up the sleeves on his stone-colored quarter-zip. His hair started to gray when he was 9 years old, long before the New York Times identified him as the finance world’s “smart-alecky boy wonder” in 2011. We were on the ninth-floor headquarters of Pershing Square’s offices on 11th Avenue, in the part of Hell’s Kitchen dominated by car dealerships; there’s a Land Rover showroom on street level and a lab for Oxman’s stealth-mode start-up on the fourth floor. The day before we spoke, demonstrators from Al Sharpton’s National Action Network had gathered at the entrance of Pershing Square for its now-weekly protest of Ackman’s crusade against DEI initiatives.

While Ackman’s campaign had suddenly made him a bogeyman of the left, he has long been a Democrat, other than the time he registered as a Republican to vote in a primary for Mike Bloomberg. The Pershing Square lobby has a Ukrainian flag on the wall, and the bathrooms still have a reminder to sing “Happy Birthday” to yourself when washing your hands (Ackman was among the earliest to support COVID lockdowns and, later, vaccines). “I’m not some archconservative,” Ackman told me. “But now I’ve been accused of being racist, a white supremacist, and right-wing as a result of all this.” He said that “what left means today is not a party I want to be associated with,” and if that means he has suddenly found common cause with the worst sort of right-wing culture warriors, so be it. When a special-counsel report in early February found that Joe Biden was “an elderly man with a poor memory,” Ackman joined a chorus of gleeful conservatives in piling on the president, tweeting, “Biden is done. There is no chance he will run for another term.”

Ackman has never been shy about speaking his mind — the entry in his high-school yearbook includes the quote “A closed mouth gathers no foot” — but his sudden emergence as a political activist, after a career defined by shareholder activism, has taken even some of his friends and supporters by surprise. “I never thought of him as leading a movement,” Peretz told me. “And he doesn’t quite lead a movement, does he? I mean, he leads himself.”

Ackman believes that he does have an army behind him — that everything he has been talking about, especially when it comes to DEI, is “sort of what everyone has wanted to talk about but has been afraid to.” While we spoke, an assistant carried a pink file folder into the conference room that was stuffed with handwritten letters from supporters. (One was a “Certificate of Commemoration” made out to Bill Ackman for “cleaning out the swamp.”) Ackman didn’t see himself in Patrick Bateman, but he had spent a few days in January posting quotes from Gladiator and retweeting his newly formed legion of reply guys as they posted AI-generated images of Ackman as a Roman general. “Welcome to the posse,” Ackman wrote to one. “Let’s roll.” The movie, which Ackman told me is one of his favorites, certainly has themes he is eager to identify with: betrayal by the elites, the importance of winning the crowd, the perils of attacking a man’s family. Ackman took particular inspiration from Gladiator’s opening scene, which he posted on X. “You have the barbarians on the other side, and they chop someone’s head off and then the Romans go and kill the barbarians,” Ackman said. “I mean, Business Insider — they’re the barbarians.”

After her forced resignation from Harvard, Gay wrote an op-ed in the Times warning that “this was merely a single skirmish in a broader war to unravel public faith in pillars of American society,” imagining a future in which public-health agencies and news organizations fall victim to the kinds of attacks that toppled her. A week later, Elon Musk encouraged Ackman to sue Business Insider. Ackman seemed wholly at peace with the damage he has left in his wake, amplifying conservative jeers that Gay got her job only because she was Black and doing harm to larger causes he previously supported. He came to the conclusion that it was incumbent on him to sound the alarm about what was happening not only at Harvard but in the multiheaded hydra of institutions that make up the liberal elite Ackman has been a part of since his youth and that he now believed was indoctrinating his children, allowing antisemitism to spread, and coming for his wife. The elites, charged with managing society, had been overrun. It was time to take back control.

Aside from some of “the torch stuff” during the Trump years, Ackman says he didn’t think much about anti-semitism before last fall. The Harvard quotas were from the 1920s, and while the affluent Westchester suburb of Chappaqua where he grew up had covenants that kept Jews and Blacks out for years, they were outlawed by the 1960s, when the Ackmans moved to town. Ackman’s father, a successful New York commercial-mortgage broker, had continually encouraged him to devote more of his charitable giving to fighting antisemitism, right up until his death in 2022. But Ackman largely brushed off the suggestion. This past September, Ackman, who invested $10 million in Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter, defended Musk against accusations that X had become fertile ground for antisemitism. “Elon has basically opened up Twitter,” he said. “The downside to a very open format is there’s gonna be some hate speech.”

Then October 7 happened. What launched Ackman’s crusade was an open letter signed by more than 30 student groups at Harvard that began with the sentence “We, the undersigned student organizations, hold the Israeli regime entirely responsible for all unfolding violence.” Ackman was one among many Harvard alums, including former university president Larry Summers, who were offended by the insensitivity of releasing the statement hours after 1,200 people were killed in Israel. “The analogy is if the KKK kills a bunch of Black people and you had people saying the Black community is solely responsible,” Ackman argued. He pulled out his phone to find a text he had received in October from another finance-world executive asking if there was a way to get “the names of the students in the organizations that signed these resolutions, so I don’t accidentally hire heartless morons upon their graduation. Do you have any ideas how to publicly ask? As you know, I’m just a simple Yalie.”

Ackman took the call to X. “The names of the signatories should be made public so their views are publicly known,” he wrote. The next day, a right-wing group parked a truck in Harvard Square with a screen broadcasting the names of students affiliated with groups that had signed the letter. (Ackman said he had no involvement with the truck.) While Ackman’s position got plenty of support — Kenneth Griffin, another Harvard billionaire, described signing such a letter as “unforgivable” — others wondered about the value of calling out students for a hastily conceived open letter that had attempted to place the attack in a broader context. “I think Bill’s getting a bit carried away,” Summers said at the time. “Asking for lists of names, that’s the stuff of Joe McCarthy.”

Ackman didn’t mind the outrage. “It was kind of great,” he told me. As Harvard’s campus grew increasingly divided, Ackman says he reached out to two friends who were members of the Harvard Corporation board, which oversees the university: Tim Barakett, a New York financier who graduated a year before Ackman, and Tracy Palandjian, who also served on Pershing Square’s board. (“I don’t know if we’re friends anymore,” Ackman told me.) He pressed for a meeting with Gay and the board; when that went nowhere, he told Barakett and Palandjian that a group of ten or so alumni was organizing a public letter. He sent the board members news articles alleging a rise in antisemitism on campus as well as a satirical piece — “Harvard installs Jew detectors at all entrances” — from the Babylon Bee. “I’m like, ‘It’s becoming a joke,’” Ackman told me.

People on campus started to notice Ackman. “I didn’t even know who Bill Ackman was, but I’m on X — for my sins — and that’s where I became aware of him,” said Rabbi David Wolpe, a visiting scholar at Harvard whom Gay appointed to serve on an antisemitism advisory board. Another campus rabbi, Hirschy Zarchi, who runs Harvard’s Chabad chapter, saw Ackman as a crucial spokesperson. “When Bill started to speak out, it gave permission for other people to speak out,” Zarchi told me. “It shifted the conversation.” He invited Ackman to campus for a town hall, but even some of Ackman’s supporters were wary of his involvement. “People were widely unhappy with Ackman showing up,” a Jewish student at Harvard who shared Ackman’s concerns about antisemitism told me. “I remember talking to my friends about it being a mistake because he represents the doxing.”

On November 1, Ackman took a seat in front of a lecture hall on campus in a blue suit and sneakers. He got choked up as he told the crowd about his great-grandfather emigrating from Ukraine to America and thanked the organizers for procuring a box of Kleenex (“Harvard Business School — they know how to do logistics”). Ackman offered advice to the students — “I would stay off social media, even though I’m not a good example” — and encouraged them to remain optimistic. He said that he was in “a WhatsApp group with probably 50 billionaires” that was “very focused on Israel,” and he cited Jared Kushner as another Harvard graduate looking for ways to economically rebuild Gaza. As the students expressed frustration that the administration wasn’t responding as proactively as they wanted to reports of antisemitic activity on campus, Ackman compared Gay’s conduct to the way President Trump had enabled a range of deplorable demonstrations from his supporters. The group sent him off with a standing ovation.

Ackman left the event filled with indignation. “We should speak before I go nuclear,” he wrote to Palandjian and Barakett. Barakett helped set up a 45-minute phone call between Ackman and Penny Pritzker, the head of the Corporation board. “It was such a disappointing conversation that I sat down and wrote that letter,” Ackman said: a six-page, single-spaced missive in which he told Gay he had “lost confidence that you and the University will do what is required.” (A person close to Pritzker said the conversation had been equally disappointing for her and that Ackman had been “verbally abusive” on the call, which Ackman denies.)

Ackman seemed to relish his central role in the drama. When I asked why the group letter from ten alumni had never come together, he said, “Because I wrote one.” He posted his letter to Gay on X and, two days later, went on Squawk Box to continue pressing his case. He says he sent a clip of his appearance to Barakett and Palandjian and asked them to play it in the boardroom.

That night, Ackman and Oxman hosted a dinner at their Upper West Side apartment, a gathering of World Minds, an “invitation-only community” funded by the media conglomerate Axel Springer that is a kind of rotating series of Davos-lite dinner parties — the kind of places where VIPs discuss the world’s problems over cocktails (Oxman is a member of the group’s advisory board). The featured guests were two members of the World Minds network: David Petraeus, former CIA director and current partner at the private-equity firm KKR, and Avi Loeb, an Israeli astrophysicist at Harvard. The war in Gaza had been raging for a month, and Petraeus gave a dispiriting talk about the broader geopolitical fallout. Later in the evening, in a call for dialogue among different tribes, Paola Antonelli, a curator at MoMA, offered a thought. “Love the aliens!” she said.

Loeb took the idea and suggested looking for hope from above. “My personal belief is that the Messiah will arrive, not necessarily from Brooklyn, as some Orthodox Jews believe, but rather from outer space,” Loeb told the group. The extraterrestrial Messiah’s message, he said, would be to stop fighting over territory here “because there is much more real estate available throughout the universe.” Back on Earth, Loeb listened while Ackman said he was hopeful that Gay would respond to his letter. “I’m a theoretical physicist, so I get paid to make predictions, and I said to him, ‘I don’t think you will,’” Loeb told me. “The last thing Harvard would do is admit their mistakes.”

Ackman believes that our lives are often fated from birth. “I have a view that people become their names,” he told me. “Like, I’ve met people named Hamburger that own McDonald’s franchises.” We’d been talking for nearly an hour and a half when Ackman asked me what my name was, hoping to offer a diagnosis. After he seemed momentarily stumped by my surname, I offered him my first name, which he misheard as Reed. “Read … write,” he said, before turning back to himself. “So, my name is Ackman — it’s like Activist Man.”

For decades, Ackman’s activism was largely confined to the business world. After graduating from Harvard Business School in 1992, he co-founded a hedge fund called Gotham Partners with backing from a small group of investors, including his father and Peretz (who gave him $250,000). He came to specialize in shareholder-activist campaigns, in which an investor acquires a small but sizable stake in a company in order to force it to make changes. The strategy could produce huge successes, especially with some of the contrarian bets Ackman became known for, as well as embarrassing failures. Above all else, being a shareholder activist requires a fervent commitment to your own beliefs. Another hedge-funder once told Vanity Fair that Ackman personified an industry maxim: “Often wrong, never in doubt.”

In 2012, Ackman waged his most infamous activist battle: a merciless campaign against Herbalife, a multilevel-marketing company that hawks dietary supplements. Ackman argued that the company was a pyramid scheme and that federal regulators would shut it down. “This is the highest conviction I’ve ever had about any investment I’ve ever made,” Ackman said at the time. He had taken a sizable short position and promised that he was “going to the end of the earth” to prove himself right.

In certain respects, Ackman was vindicated — regulators made Herbalife pay a $200 million settlement and alter its business model — but he had overlooked an inherent risk that came with his personality: how much some people dislike him. His cockiness had become legendary in an industry that has never lacked for self-assurance, and after he placed his Herbalife short, Carl Icahn, another hedge-fund billionaire, took the opposite side of the bet, plowing money into the company’s stock seemingly out of spite. (Ackman had previously spent seven years suing Icahn over a few million dollars — petty cash for two titans.) At one point, while Ackman was making a live appearance on CNBC, Icahn called in to the show. “I’ve really sort of had it with this guy Ackman,” Icahn said. “I had dinner with him, and I gotta tell you, I couldn’t figure out if he was the most sanctimonious guy I ever met in my life or the most arrogant.” Ackman remained calm as Icahn attacked. “I went to a tough school in Queens, you know, and they used to beat up the little Jewish boys,” Icahn said. “He’s like one of the little Jewish boys crying that the world is taking advantage of him.” Ackman continued his attack on Herbalife but couldn’t bring the company down. When he finally bailed on the bet in 2018, he had lost $1 billion.

Ackman still bristles at mention of the Herbalife experience. (“I wasn’t whiny, and no one beat me up,” he said when I brought up the Icahn exchange.) It also led him to swear off bombastic activist campaigns. Pershing Square now largely invests in big, boring brands — Starbucks, Hilton, the holding company that owns Burger King and Popeyes — that meet a set of core principles enshrined on a kitschy stone tablet that sat behind him in the conference room where we met. Pershing’s most recent annual report expressed excitement about its investment in Chipotle on account of the chain’s successful introduction of chicken al pastor. The shift brought a calmer way of life for Ackman and considerable success for Pershing, buoyed by an incredible bet Ackman made in February 2020 predicting that the economy was about to be devastated by COVID. The trade turned $27 million into $2.6 billion in a matter of weeks.

Ackman’s campaign against Harvard was in many ways a return to his roots. “It’s the same thing,” he told me. “As an activist, we usually have only a small percentage of the stock — 5 percent or 10 percent — and we get a corporation to do something. How do you do that? You win by the power of the idea.” But others who worked with him saw something new — Activist Man unleashed. “This is different, and maybe even better, for Bill,” a longtime Ackman associate told me. In business, he often had to wait for an annual board meeting to exert real pressure, and any substantive comment he made about a company was vetted by lawyers. “With political speech, he has no filter,” the associate said. “You’re getting direct nectar from the source — you’re getting the royal jelly directly from the queen.”

Ackman says that his activist investing taught him the importance of doing your own research. Back in 2020, he told me, he “understood the good reason for a societal feeling of guilt in the days and weeks and months after George Floyd’s death — that we really gotta take a harder look at what’s wrong with society.” Ackman says his foundation has given away more than $600 million to largely progressive causes, from the Innocence Project to a fund for Dreamers at CUNY, and Pershing Square itself has a diversity-and-inclusion committee. Ackman told me he was eager to respond to a letter from several members of Congress asking for data about diversity at the company, boasting that Pershing’s eight-person investment team includes a Muslim Pakistani, an Iranian refugee, a Canadian Jew, a Hindu born in India, a Mexican American, an Italian Catholic from the South Bronx, and — diversity comes in many forms — a billionaire from Chappaqua. (Only one member of the team, the daughter of Chinese immigrants, is a woman.)

In short, he has long supported efforts to increase diversity. But last fall, Ackman said, he had several extensive conversations with two different Harvard faculty members — he declined to name them — who suggested that he look more closely at the university’s DEI programs. “A guy I’ve known since college, very senior, was the one who really helped me understand this stuff — the whole oppressor-slash-oppressed narrative,” said Ackman, who felt that Jews had been unfairly wedged into the former category. “I’d never even heard that before, and I’m supposed to be an aware person.” Someone else sent him the book America’s Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered Everything, by Christopher F. Rufo, the conservative activist who led the effort to stigmatize critical race theory before turning his sights on DEI. Then came the deluge. “I started following various people on Twitter,” Ackman told me. “I started getting the download.”

Ackman joined Twitter in 2017, when Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker recommended the platform over dinner at Peretz’s house. “I use Twitter as a source of information — I should say ‘X’ to be respectful to Mr. Musk,” Ackman told me. “You can just follow people who are experts, or present as experts, in various things.” Ackman credits his big COVID bet to insights about the virus circulating on Twitter before they were covered by the press. (“I’ve comfortably covered the cost of my blue check,” he said last year.) Now, Twitter was helping him piece together a theory about what had happened at Harvard. By December of last year, he had come to believe, like many of the conservative activists he was now following, that the situation with his daughter had not been a one-off and that DEI initiatives and adjacent ideologies were responsible for a swath of ills facing the university: that DEI was in fact the “root cause” of the antisemitism at Harvard; that its predominance was squelching the academic freedom of anyone — namely conservatives — who wished to question facets of its ideologies; and that, when hiring Gay, Harvard had declined to consider “non-DEI” candidates.

On December 5, Ackman was sitting in his barber’s chair watching Gay and the presidents of MIT and Penn answer questions from Congress. When all three appeared unwilling to condemn calls for the genocide of Jews, falling back on a defense of free speech, he called his director of communications and asked him to cut a clip of the exchange. “He emails it to me while I’m sitting there getting my haircut, and I write that tweet and send it out,” Ackman told me. “And it changed the course of history.”

That was a characteristically Ackmanian assessment of his own significance, but the clip did help the moment go viral. (It has been viewed 107 million times.) Ackman sent another letter to Gay, this time calling for her resignation, but the Corporation stood by her. His machinations weren’t working, and he gave up trying to operate behind the scenes. “I wasn’t really doing anything except whatever I was doing on Twitter,” he told me. A week after the hearing, several journalists published allegations that Gay had committed plagiarism in her academic work. Ackman knew a pressure point when he saw one, and he posted on X about the accusations more than a dozen times in the weeks that followed. “After they refused to let her go because of failures of leadership — let’s put it this way,” Ackman said to me. “I wasn’t unhappy if she had to go for this.”

When Gay finally resigned, on January 2, Ackman was in the Dominican Republic with Oxman and their daughter. It was the penultimate night of his vacation, but Ackman couldn’t resist taking a victory lap and spent nine hours, from 6 p.m. to 3 a.m., writing up his 4,000-word reaction in Microsoft Word and then pasting it into a tweet.

Following the Herbalife debacle, Ackman emphasized a core principle to help Pershing Square judge potential investments: What’s the expected return on brain damage? In other words, the potential reward needs to outweigh whatever headaches might emerge along the way. When I asked Ackman about his current campaign, he said that the benefits were “enormous” and worth the risk. “The only brain damage was some shrapnel that hit my wife,” he said.

Ackman met Neri Oxman in 2017. They were both separated from their spouses — Ackman has three daughters with his first wife — and were introduced by Marty Peretz. Oxman was at the time a professor at MIT, where she ran a design lab. She has exhibited her unusual work — sculptures made from shrimp shells, masks that mimic the shape of human breath — everywhere from MoMA to the Centre Pompidou. She gained worldwide notoriety in 2018 when tabloids reported that Brad Pitt had been visiting her lab, suggesting the two were an item. Ackman takes every opportunity, in interviews and public appearances, to tell anyone who will listen that his wife is among the most beautiful and intelligent women on the planet. He described one of her recent podcast appearances as “breathtaking.”

Ackman said being married to Oxman, who is Israeli, gave him a “visceral connectivity” to the October 7 attack, and that she had been his “quiet partner” throughout the fall. While Ackman tweeted about his visit to Cambridge, Oxman privately attended a lunch the same month hosted by the MIT Israel Alliance. “It was partially group therapy and partially just that stressed-out students need free food,” Talia Khan, the group’s president, told me, adding that many MIT students knew Ackman as “that guy who is Neri’s husband.” Oxman had largely shied away from making public comments. “She kept debating whether she wanted to post,” Ackman said. “She did one thing and got a bunch of negative stuff that just wasn’t for her. I said, ‘Sweetheart, you know what? Let me be the tip of the spear on this thing.’”

The shrapnel from Ackman’s attacks landed two days after Gay’s resignation, when Business Insider published a story alleging that Oxman, like Gay, had committed plagiarism in her dissertation: Multiple paragraphs from a paper by Oxman appeared verbatim in work by other authors. “I thought the obvious, which is that they were coming after me by going after my wife,” Ackman said. After the story was published, Oxman posted a lengthy tweet in which she admitted to neglecting to properly quote the original authors. A day later, Business Insider followed up with another story highlighting sections of Oxman’s dissertation that were taken from Wikipedia without citation, as well as uncredited passages from two other papers Oxman had published. This time, Ackman tweeted that he would be investigating the work of every professor at MIT for plagiarism — and, for good measure, the work of Business Insider’s reporters.

Ackman didn’t see anything wrong with jumping to his wife’s defense after having weaponized the allegations of plagiarism against Gay. “I don’t think I was being hypocritical at all,” he said. Ackman did run his own Harvard thesis through a plagiarism detector and was relieved when it came back clean. “I was shivering in my boots,” Ackman told me. “The irony would’ve been something.”

Instead, Ackman spent the weekend trying to pressure Business Insider to retract the stories and detailing his effort to do so on X. He called a “director” at Business Insider, who promised to look into the issue, agreeing that the definition of plagiarism had become so broad as to be meaningless. (While Ackman didn’t name the director, employees at Business Insider recognized his writing style — “If you ever get sick of managing money, you will be in great demand as a writer. I know from experience that it is harder than it looks!” — as belonging to Henry Blodget, the site’s founder and chairman, who is fond of using exclamation points.) Ackman continued pressing his case up the corporate ladder, talking to a board member from Axel Springer, which owns Business Insider, and texting executives at KKR, which owns Axel Springer. “We are the number one trending with 38.6k post and the princess of Wales is number 2 at 2,998,” Ackman wrote to Blodget. In a post on X, Ackman said that rectifying the situation would require only seven simple steps, including Axel Springer taking action to “depublish” the stories about Oxman and then having its CEO, Mathias Döpfner, fly from Germany to New York immediately to sit down with Henry Kravis of KKR and adopt a “settlement fund” to “compensate all those who have been victimized” by Business Insider, with the proceeds of any settlement for Oxman going to her company “so she can accelerate the incredible work she does.” After a few days went by, with no end to the tweeting in sight, an Axel Springer spokesperson told a reporter at Puck that “most people underestimated the way that Bill Ackman is completely losing it.”

Ackman kept posting. He claimed the story had been planted, possibly by someone from MIT, and accused a Business Insider editor of being “a known anti-Zionist” with an agenda. The Gladiator memes started rolling out. Ackman tried to exonerate Oxman by pointing out that the university’s plagiarism policy didn’t explicitly object to taking content from Wikipedia and by asking if anyone besides his wife had even been accused of plagiarizing definitions from Wikipedia before. (There is, in fact, a Wikipedia page dedicated to people who have been caught plagiarizing Wikipedia.) Ackman estimated that he had spent “110 hours or so” battling the case on his wife’s behalf and called one of several long posts he wrote in an attempt to exonerate Oxman “the best and most important thing I have ever written,” tweeting that “I am extremely fast writer, and I am powered by a profound love that is infinite.”

Oxman, for her part, wasn’t sure what to make of her husband’s chivalrous tweeting, which had drawn even more attention to the allegations. (Through Ackman’s spokesperson, she declined to comment for this story.) Ackman wrote on X that the pressure from the Business Insider stories “could have literally killed her” and that he had seen others commit suicide in similar circumstances. “She was in a pretty dark place,” Ackman told me, adding that he tried to nudge her toward finding a silver lining: “I’m like, ‘Look, you didn’t do anything wrong; we’ll get this fixed,’ and ‘Actually, the more negative press, the -better. Once we turn this around, it’ll be good for your company.’” He wasn’t sure the pitch had landed — “There were times when she said, ‘Please don’t tweet anymore’” — but he defended himself by pointing to memes online suggesting he had become a hero to wives everywhere. “There’s a meme going around that apparently I’m causing a lot of marriages to have trouble,” Ackman said. “Like this one where a husband emails his wife, ‘Honey, I did the dishes.’ And she’s like, ‘Big fucking deal. Did you see what Ackman’s doing for his wife?’”

Ackman has long suffered from main-character syndrome. As his fight against Harvard expanded to include a galaxy of grudges, he began referring to himself as the situation’s protagonist. (This made Oxman “the wife of the protagonist.”) While we talked in his office, Ackman told me a story, apropos of very little, about a weeklong trip he took to Japan in the early 1990s during which he stayed with a family whose patriarch worked in the video-game industry. Years later, Ackman found out about a Japanese video game called Go! Go! Ackman! The game, to quote Wikipedia, follows “a demon child named Ackman who harvests souls for the Great Demon King.” The real Ackman’s spokesperson held up an iPad with an image from the game for me to see — the demon child had prematurely gray hair. “I think that’s me,” Ackman said. “I never got royalties.”

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Ackman joined a Twitter Spaces conversation with Elon Musk and Dean Phillips, the Minnesota representative running a long-shot campaign against Joe Biden for the Democratic nomination. Ackman had endorsed Phillips, and he told the 20,000 listeners, including the accounts for Marjorie Taylor Greene and @EndWokeness, that he was “ashamed” of today’s Democratic Party. He has predicted that Trump will win if Biden is the Democratic candidate. Before settling on Phillips, Ackman had looked for alternatives in Harvard graduate Vivek Ramaswamy, Harvard graduate Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and Harvard graduate Jamie Dimon, whom he had encouraged to make a run. Would Ackman, another Harvard graduate, ever consider running himself? Some of his friends think he might. “He’s going through a period of growth — a period of expansion — because it turns out this political activism is quite fun, and I believe the adulation he feels will push him to do a lot more of it,” the longtime Ackman associate told me. “I wouldn’t be surprised if we see him running for office. And if you ask what office, you don’t know Bill Ackman.” Ackman himself said in December that “if the country wanted me at some point, I would be open to it.”

For much of January, he had focused his energy on a smaller election, backing four candidates running for Harvard’s Board of Overseers in the hope of pressing the university on free speech, reforming DEI, and addressing financial mismanagement of the endowment. On the fourth Tuesday in January, he joined a Zoom in support of the candidates that was being hosted by the Harvard Business School Club of Pittsburgh. At one point, Ackman’s 4-year-old daughter walked on-camera, where he was sitting in front of an imposing black Louise Nevelson sculpture that hung on the wall behind him. “Our goal is to make Harvard a school she wants to go to in 14 years,” Ackman said.

But despite all the supposed fervor for change at the university, Ackman’s candidates fell short of the 3,000 signatures needed to get on the ballot. (The candidates blamed complications with Harvard’s online-voting system, which Ackman described as “election interference.”) He told me he remains undeterred: He is close to signing a contract with an AI company to conduct his plagiarism review and still plans to file a lawsuit against Business Insider. A few days before we met, he had invited Dave Portnoy, the founder of Barstool Sports, who unsuccessfully sued Business Insider for defamation last year, to visit him at Pershing Square. “I have a historical record of everything now,” Ackman said, pulling his phone out of his pocket to show me an old text. “It’s good for discovery.” He said he plans to pursue his various campaigns “to the end of the earth.”

The last time Ackman publicly vowed to do that, against Herbalife, he lost his investors $1 billion. And even some of his supporters at Harvard wondered whether his online vitriol was creating a proxy war outside of campus that made actual dialogue more difficult. “I think the alternative of being silent is not a good thing,” Ackman told me. Last week, he also announced that Pershing Square would begin wooing retail investors to a new fund it intends to list on the New York Stock Exchange, which meant the 400,000 new followers Ackman has picked up on X since October might be a boon for business after all.

It has been disorienting to see concerns about Hamas’ attack and the war in Gaza, and its unceasing death toll, subsumed in the U.S. by a war for the soul of the Ivy League and questions about the definition of plagiarism. But Ackman believes that his campaign is critical for the future of America and that the masses are with him. He said strangers have continually come up to praise him for his work: in the Dominican Republic; at an Orthodox wedding in New Rochelle; at hotels, where people leave thank-you notes with the concierge. “I can’t walk around New York City, or anywhere, without people coming up to me,” he said. “I was in a restaurant two weekends ago — the whole restaurant gave me a standing ovation.”

I asked where the restaurant was. Ackman smiled. “This incredibly diverse community called the Hamptons,” he said.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Axel Springer owns World Minds. Axel Springer is an investor. It also incorrectly stated when a photo of Bill Ackman was taken at Harvard.

Related

- How Bill Ackman’s $25 Billion IPO Plan Went Bust (at Least for Now)

- Everyone Bill Ackman Is Fighting

- What Really Happened Between Joe Biden and Bill Ackman