This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Clarence Thomas,” says Ginni Thomas in a 2018 installment of her long-running Daily Caller interview series on the subject of leadership, “you’re the best man walking the face of the earth.”

He chuckles. They sit a few feet apart in a small room near a clock, a bookshelf full of file folders, a plant in a wicker basket.

“It’s an honor to interview you.”

“Well, I’m really stressed out about this interview,” he says, not smiling, then smiling, then laughing. Halfway through their time together, Clarence Thomas is talking about coming from a place where many of the adults around him were illiterate. He’s talking about the deep pleasure he finds in old books, “like Christmas every day,” the sense of gratitude for this knowledge denied his aunt, mother, grandfather.

“Now I know you think I’m a little different,” he says. “And I am. But … you get to read Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson — many people kind of roll their eyes — ”

Clarence, perhaps reading the lack of interest in Ginni’s eyes, starts laughing.

“But just think of all the people,” he says, motioning forward with his hand in a Clintonian gesture of explanation, “who were around him. Whether it was Edmund Burke or Adam Smith.” He laughs again. “I mean, wouldn’t you want to read Boswell’s Life of Samuel” — he can hardly get the words out now, he’s laughing so hard — “Johnson?”

Ginni laughs quietly.

“I’ll put it on my list, Justice,” she says with a little flick of the wrist and coy look into the distance.

“I’ll lend you my copy,” he says with a straight face.

“As long as you underline it for me.”

He loses it.

“Okay,” she says, ready to move on with her list of questions.

“What about,” he says, leaning in, very serious now, “Wealth of Nations?”

“Just — ” she says.

And he loses it again, a high-pitched laugh that tilts him forward in his chair.

“I have a life to live,” she says, sighing.

“Okay,” she says. “All right.”

“Oh God,” he says, “you make me laugh.”

Ginni has brought questions. She’s trying to get back on track. There’s more to mine on the subject of leadership.

“Um,” she asks, “if someone asks for your advice when they’re getting married, what would you suggest?”

“I keep a sign on my desk,” he says: “Don’t make fun of your wife’s choices, you were one of ’em.”

He’s laughing again.

“Thank you. I really appreciate that. And that’s so true.”

“Okay. What — ”

“Plus I love my wife. My wife cracks me up … You and I are very different. You don’t read The Life of Samuel Johnson, for example.”

And they’re laughing again.

“Exactly,” she says.

“Oh God,” he says. “I love you.”

There is a certain rapport that cannot be manufactured. “They go on morning runs,” reports a 1991 piece in the Washington Post. “They take after-dinner walks. Neighbors say you can see them in the evening talking, walking up the hill. Hand in hand.” Thirty years later, Virginia Thomas, pining for the overthrow of the federal government in texts to the president’s chief of staff, refers, heartwarmingly, to Clarence Thomas as “my best friend.” (“That’s what I call him, and he is my best friend,” she later told the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol.) In the cramped corridors of a roving RV, they summer together. They take, together, lavish trips funded by an activist billionaire and fail, together, to report the gift. Bonnie and Clyde were performing intimacy; every line crossed was its own profession of love. Refusing to recuse oneself and then objecting, alone among nine justices, to the revelation of potentially incriminating documents regarding a coup in which a spouse is implicated is many things, and one of those things is romantic.

“Every year it gets better,” Ginni told a gathering of Turning Point USA–oriented youths in 2016. “He put me on a pedestal in a way I didn’t know was possible.” Clarence had recently gifted her a Pandora charm bracelet. “It has like everything I love,” she said, “all these love things and knots and ropes and things about our faith and things about our home and things about the country. But my favorite is there’s a little pixie, like I’m kind of a pixie to him, kind of a troublemaker.”

A pixie. A troublemaker. It is impossible, once you fully imagine this bracelet bestowed upon the former Virginia Lamp on the 28th anniversary of her marriage to Clarence Thomas, this pixie-and-presumably-American-flag-bedecked trinket, to see it as anything but crucial to understanding the current chaotic state of the American project. Here is a piece of jewelry in which symbols for love and battle are literally intertwined. Here is a story about the way legitimate racial grievance and determined white ignorance can reinforce one another, tending toward an extremism capable, in this case, of discrediting an entire branch of government. No one can unlock the mysteries of the human heart, but the external record is clear: Clarence and Ginni Thomas have, for decades, sustained the happiest marriage in the American Republic, gleeful in the face of condemnation, thrilling to the revelry of wanton corruption, untroubled by the burdens of biological children or adherence to legal statute. Here is how they do it.

1.

Things About Home

My husband’s childhood was so unlike mine,” Ginni Thomas once said. “I know when I first went down to Pin Point I said, ‘Clarence, I can’t understand a word that they just said’ … I just try to listen and smile.” Numerous attempts have been made to diminish the lonely hardship into which Clarence Thomas was born — he was “middle class,” one will read; biographers cannot find corroboration on various slights he claims to have suffered — and yet the objective circumstances suggest a material and emotional deprivation that renders all of this at best irrelevant. He emerged from that childhood not a conventional conservative in any sense, but something closer to what Stephen Smith, Thomas’s first Black clerk and the author of “Clarence X?,” calls Black nationalist.

“There is nothing you can do to get past Black skin,” Thomas once told Juan Williams. “I don’t care how educated you are, how good you are at what you do — you’ll never have the same contacts or opportunities, you’ll never be seen as equal to whites.” His is a fundamentally fatalistic vision of white liberals, whose every attempt to “help” is pure vanity, a more dangerous, because more dishonest, extension of the white supremacy they profess to deplore. His views on school busing are instructive: “I wouldn’t have gone into South Boston. It would have been taking my life in my hands for me to do so. Why, then, were innocent children being made to do what a grown man feared?” This is not a question earnestly posed, because Thomas has in countless speeches articulated the motives of white liberals disrupting Black life: They act to assuage white guilt, to improve the aesthetics of the ruling class, to stoke the delicate self-conception of those who would never willingly cede power, all of it in service to a supremacist status quo. He prefers, he has said, the directness of southern racism to the subtlety of northern condescension.

The details are by now familiar: Thomas, abandoned by his father, raised in isolated coastal Georgia, where he was teased by lighter-skinned Black children for his particularly dark skin. The one-room, one-lightbulb cottage; the local dialect, Geechee, for which Clarence was also teased.

Each episode of Clarence’s young life would showcase a distinct American horror. His little brother accidentally burned down the cottage, and the boys moved to Savannah. “Urban squalor,” he called these living conditions, “hell.” At night, his mother and brother shared a bed; he slept, cold and hungry, on a chair. Unable to keep them warm and fed, Leola Williams begged her father to take them in. “The damn vacation is over,” he told the boys, though the boys did not know what vacation he was talking about. “He meant to control every aspect of our lives,” writes Thomas in My Grandfather’s Son, a book in which he describes said Grandfather as both a looming “dark behemoth” subjecting them to vicious punishment for the transgression of arbitrary rules and “the greatest man I had ever known” in the space of a page. Daddy, as they called him, filled the boys’ every hour with work and refused them work gloves when their hands blistered. “He never praised us,” Thomas writes, “just as he never hugged us … In his presence there was no play, no fun, and little laughter.”

Clarence was living in his grandfather’s house the year his future wife was born. Virginia Lamp grew up in a lakeside home the Omaha World-Herald once called “a resort residence” and Virginia’s mother described as “away from all the rush of city life,” which is to say in a 142-home development her developer husband had established 30 minutes outside Omaha, built around two ersatz lakes he had dredged himself. The carpeting, we learn from the World-Herald’s strangely advertorial account of the home’s interior, was chosen specifically to “cope with sand that might be brought in from the beach,” and while the drive might seem a burden, the family found it salutary to be far removed from the apparent stress of central Omaha. Entertaining is easy, Marge Lamp, Ginni’s mother, told the World-Herald in 1969, when one has both a sailboat and a motorboat available for guests.

Ginni, the youngest of four, attended Westside High School, an extremely white institution in a smaller district separate from Omaha’s larger school system. Her childhood was, to an astonishing degree, structured to protect her from the realities her future husband had endured, and yet here also loomed some unseen enemy, an invisible threat to the existence of easy entertaining. “Positive information is the best defense against ridicule of our flag, our Christian heritage, our free enterprise system and our form of government,” Marge Lamp wrote in a 1969 letter to the editor, leaving the flag ridiculers unnamed.

At age 12 Ginni boarded a chartered plane for Washington, D.C., having been selected as a page for the GOP Women’s Conference, where she would sport a sash and a top hat; partisan costuming would continue to be a theme throughout her life. Her childhood was social where Clarence’s had been isolated, a succession of parades and rallies and fundraisers, the sense that the world could, though determined voluntarism, be changed. Ginni’s mother supported Phyllis Schlafly’s crusade against the Equal Rights Amendment, and hosted at her home, there on the sandproof carpet, like-minded nationally known speakers, such as Frederick Schwarz of the Christian Anti-Communism Crusade. Marge Lamp, or as she put it in her campaign literature, “Mrs. Donald G. Lamp,” ran for state legislature under the theme of “common sense” and told the paper she’d commute to Lincoln and be back home at night, such that her husband would not miss many meals. She was, according to friend and former congressman Hal Daub, a positive, active, affable, civic-minded presence in Omaha, one-half of a marriage of equals. Her best campaigners, she said, were her children. She lost, but she had passed on something in the attempt.

“That was my first real campaign,” Ginni told a reporter in 1974. She was a high-school student canvassing for Republicans in the age of Watergate, which, she assured the reporter, “was just Nixon and his people, not the Republican Party.” Why campaign when you’re too young to vote? “Because the party needs us,” she said, sloshing through the rain to deliver more talking points. Ginni was a compulsive joiner. As a “warrior woman,” she donned a shield and cheered on the football team. Daub, a centrist Republican, would later employ her in D.C. She stood out in his office as social, eager, and unusually knowledgeable — “a wonk.”

In the spring of 1986, Clarence was a 37-year-old divorced single father and one of D.C.’s most eligible bachelors according to Jet magazine, which we can be fairly certain Ginni did not read. He was the head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a rise from poverty that a traditional conservative would describe as a rags-to-riches individualist American triumph, but this is neither Clarence Thomas’s experience nor the story he chooses to tell.

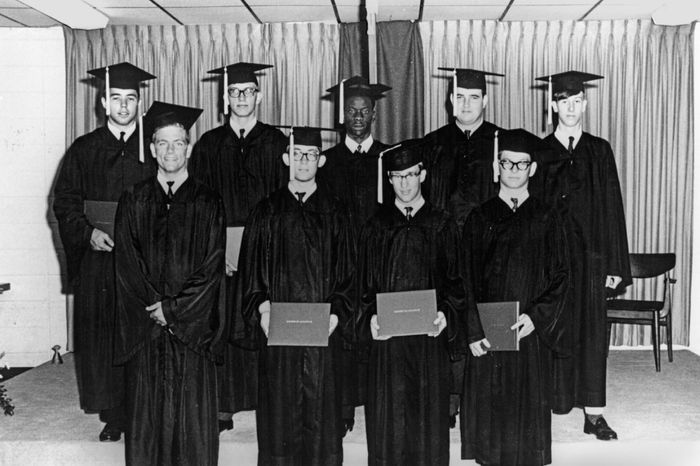

There had been, after the brief and defining comfort of his Black Catholic elementary school, a tour of white institutions where Clarence was made to endure a succession of racist humiliations. He was one of only two Black children in his high-school seminary, which is to say constantly surrounded by white adolescent boys. “Smile so we can see you, Clarence,” he recalls one saying in the dark. He dropped out of his college seminary after he heard a classmate celebrating the death of Martin Luther King Jr. As an undergraduate at Holy Cross, he listened to records of Malcolm X speeches, helped found a Black Student Union, and nearly dropped out in protest of racially motivated mistreatment. He was never so invested in student life at Yale Law, where the distance between himself and his classmates appeared the difference between Pin Point and Greenwich. “I felt the difference in my bones,” he writes. “I was among the elite, and I knew that no amount of striving would make me one of them.” What other Yale Law student, gearing up for a summer home, was “sick with worry” about the “frightening prospect” of driving through the South in an unreliable old car past a Klan-sponsored billboard? Who else had to endure the strange looks of white mechanics inspecting the failing car, a “bad night’s sleep” in a strange motel when no one could fix it, and rescue, finally, from his brother?

As the head of the EEOC, burdened with debt, Thomas was a man conspicuously lacking generational wealth. He was still broke. American Express cut him off for failure to pay his bills. He could not access a credit card, and so when he did official business, incredibly, his secretary had to book him only in hotels that took cash. His apartment was full of cockroaches. He was overcome with loneliness, “lower than a snake’s belly,” and, according to his friend Armstrong Williams, liable to “bore women to death” on dates.

It was not on a date that he met 29-year-old Virginia Lamp but at an intimate roundtable on affirmative action, or, as Ginni recently put it, on the subject of “how long America needs race-preference policies to get over slavery.” Midge Decter (or “Mrs. Norman Podhoretz”) introduced Thomas to Ginni, who was then a labor lobbyist for the Chamber of Commerce. The two of them shared a cab back to the airport.

“I have some Black female friends I’d really like to put together with you,” Ginni said. Clarence laughed and said he wasn’t interested. The next time he saw her, she was soaking wet, having trudged through the rain to attend a D.C. event intended to introduce EEOC chairman Clarence Thomas to “the business community.”

They shared a professional, polite lunch on K Street; he never considered dating her, he wrote later, because he had “more than enough problems” and didn’t need to add dating a white woman to the list. Yet someone must have been interested in more, because a few weeks later, they took in an early-afternoon showing of Short Circuit, which is not the kind of thing one does with just another member of the business community. Short Circuit involves a winsome military robot who gains sentience, flees its Army pursuers, and wins freedom from its government minders by building a decoy of itself. Clarence laughed the whole way through, and Ginni laughed, just as she would decades later, at the spectacle of him laughing. “I left that dinner smiling like I’d never smiled,” Ginni said of their post–Short Circuit meal. “I was in love with this guy.”

There was an unsettledness about Ginni, projects started and dropped. She enrolled at Mt. Vernon College in D.C. and transferred to the University of Nebraska to be closer to her boyfriend, a premed student enrolled at Creighton. She then transferred to Creighton, her third undergraduate institution, presumably to be closer still, and became, naturally, Nebraska’s College Republican chair. Her parents announced her engagement to a med student, though the two never married. She worried she would never find a husband who would support her ambition. She went to law school and dreamed of representing Nebraska in Congress.

She and Clarence walked along Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, where people stared, and the couple talked about the people staring. She seemed to him uncynical, unspoiled, a person who believed in things. “She was a gift from God that I had prayed for,” Clarence said. “And then I was iffy, because I started questioning God’s package. You know, like what are you doing? You pray for God to send you someone, he sends you someone, and you say, ‘Oh, but she’s white’ or ‘She’s younger.’ He’s sent you someone. What are you talking about?”

Ginni was, according to Clarence, “willing to fight anybody, including friends and family, who objected to the match.” (“I didn’t know what to think,” was Marge Lamp’s reaction to her daughter dating a Black man.) Less than a year after the early showing of Short Circuit, they were married. Four years after that, George H.W. Bush announced his choice for nomination to the Supreme Court. “It’s going,” Ginni said, “to be fun.”

2.

Love Things

Strange Justice, a 1994 book by Jane Mayer and Jill Abramson, is astonishingly well sourced on the subject of Clarence Thomas’s relationship to “freak of nature” pornography. Here is a fellow Yale Law student describing “one of the crudest people I have ever met … profane, scatological and graphic,” given, according to Pulitzer Prize winner and Holy Cross classmate Edward P. Jones,* to using language that “would have reduced other people to tears.” An acquaintance from Yale remembers him carrying porn in the back pocket of his overalls and offering detailed descriptions of X-rated movies he had seen in downtown New Haven. Here we have the proprietor of Graffiti, a video store then near Dupont Circle, describing the kind of movies to which Thomas was drawn, at a time when adult-video connoisseurs were regularly engaging with characters like Long Dong Silver, whose 18-inch apparently prosthetic penis has since been recast as an early, heartening example of body positivity. Here a woman describes visiting Clarence in 1982 and encountering, on nearly every wall of the apartment of the chairman of the agency tasked with setting guidelines on workplace sexual harassment, posters of naked women. Thus it was that when inside the Caucus Room in the Russell Senate Office Building before the all-white, all-male Senate Judiciary Committee, Anita Hill described a man picking up a can of soda and asking “Who has put pubic hair on my Coke?” she sounded, to many in middle America, deranged, and to Clarence Thomas’s intimates, something else altogether. “I didn’t know what to think until I heard the Coke can story,” Gordon Davis, a friend of Thomas’s from Holy Cross, told Mayer and Abramson. “When I heard that, I knew he’d say stuff like that.” Confirms Edward P. Jones: “The Coke can thing did it for me.”

One person for whom the Coke-can thing did not appear to resonate was Virginia Thomas, who took these proceedings to be evidence of a presence she’d been hearing about all her life: a vast and vulgar left-wing conspiracy. The hearings had begun normally; Clarence Thomas was questioned as to his opinions and insisted that those opinions were utterly irrelevant to his unbiased application of legal precedent, and politicians on both sides pretended to believe him. He had “no agenda” on Roe v. Wade; he had an “open mind” about abortion; it would “totally undermine and compromise” his capacity as a judge to sit on any cases he had “prejudged.” He was simply an umpire, an objective arbiter of the straight truth, but a humble foot soldier of settled law as it had been defined prior to his time. News of Anita Hill’s accusations was delivered via FBI agents at Thomas’s kitchen table. Senate Judiciary Committee leader Joseph Biden called Thomas to discuss the hearings over which he would preside, and Clarence turned the receiver toward Ginni so she could hear. As Clarence tells it:

“As he reassured me of his goodwill, she grabbed a spoon from the silverware drawer, opened her mouth wide, stuck out her tongue as far as she could, and pretended to gag herself.”

This was an account of events in 1991 in an autobiography published in 2007, when Clarence Thomas was a sitting justice on the Supreme Court. That he cares to share this detail at such cinematic length (“gagged herself with a spoon” would have been more economical but less visual) suggests immense pride in his wife. This is the Ginni he loves, the one engaged by conflict, loyal and funny and true.

There had been not long before a time when Ginni’s intensity was a problem. “She went through this pattern where every guy she was dating was her guru,” said someone familiar with both Thomases. But there had also been actual gurus. Lifespring was a group some people called a “human potential organization” and other people called a cult. (“Are our people enthusiastic, intense and emotional? Yes,” the group’s vice-president said in response to this accusation.) Ginni had recently failed the bar exam. There were “trainings” in Rosslyn and Capitol Hill; in one, participants were made to remove their clothes, listen to “The Stripper,” and insult one another’s bodies. A guy you call in this kind of situation spent eight hours at Hamburger Hamlet in Georgetown deprogramming her. When she left the cult, she became deeply involved in a group focused on anti-cultism.

Ginni did not doubt her husband when a young woman accused him of describing rape scenes at work. In fact, reports Clarence, she “loved me more than ever.” Weren’t these accusations just more evidence that she had landed the ideal man, an object of crazy-making desire? “In my heart,” she said later, “I always believed she was probably someone in love with my husband and never got what she wanted.”

By all accounts, at this point, Clarence Thomas simply fell apart. “I lay across the bed and curled up in a fetal position,” he writes. “He was,” Ginni said later, “debilitated beyond anything I’d ever seen in my life.” “I have never had an experience like that,” former senator John Danforth later said. “Ever. Still haven’t. Because he was a broken man. He was just broken.” It was “spiritual warfare,” Virginia said, “good versus evil.”

It is hard to see how Clarence Thomas would have extricated himself from the fetal position without Ginni, who closed the blinds and put on Christian music and invited couples over to pray and called a neighbor to come over and give Clarence a haircut, which she did. He got up at one in the morning the night before the hearing and looked over his papers, suggestions on how to respond, and was, according to Ginni, “really confused.” She cleared the table for him. She turned on his computer. He wrote his speech on a notepad. She typed it up.

As they walked down the hallway to the Caucus Room, women standing against the walls clapped for him. They were from Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum, there to bear him up.

“Who are they?” Clarence asked.

“They’re angels,” Ginni said.

She watched the proceedings in rage, “the wrath of anger coming out of my eyes.” Why wasn’t the conversation about his heroism? Where was the celebration for obstacles he had overcome? “My name has been harmed,” he said. “My integrity has been harmed. My character has been harmed. My family has been harmed. My friends have been harmed. There is nothing this committee, this body, or this country can do to give me my good name back. Nothing.”

When the vote was called, according to Virginia’s account, Clarence was in the shower; Clarence says he was in the bath. Both say Virginia ran up to tell him he had become a justice. He “just shrugged,” according to her. According to him, his response was “Whoop-dee damn-doo.”

For almost seven years after the hearings, Thomas stayed silent during oral arguments, a silence that he sometimes explained as an aversion to “hyperactive” grandstanding (“We look like the Family Feud”) and sometimes to his childhood speaking Geechee, but that looked, to many people, like disengagement: Whoop-dee-damn-doo. He went to work, day to day, a Supreme Court justice who still owed college loans. For a man not given to lazy, reflexive patriotism, there was no great narrative moment of breaking through into a world denied him.

There had been a day when Clarence returned to his grandfather’s house with his own small son, Jamal, and left him there for a while. When he returned, he found “five or six open boxes of cereal, all of them presweetened brands.” When he had been a child, living with his disciplinarian grandfather, “the idea of opening more than one box at a time was unthinkable.” He asked why Jamal had been allowed to open so many boxes. Jamal had wanted the prizes in the cereal, his grandfather said, to Clarence’s pained and enduring astonishment, and so together they opened all of them. Why, Clarence asked, had this extravagance been tolerated? “Jamal,” his grandfather said, “is not my responsibility.”

This is an odd moment to share for an author who perceives himself as writing hagiography, but it is of a piece with the rest of the work, which is an account, across time, of loneliness, persistent racism, and grievances both justified and otherwise. The house where his ancestors were enslaved, he notes acidly, became a bed-and-breakfast billed as “a perfect honeymoon hideaway.” Thomas’s loyalty, repeatedly expressed, is not to the grandfather who denied him affection, or the country that abandoned him to poverty, but to the woman he “needed … more than anyone,” the woman who did not doubt him when doubt was merited, the woman who handed him a towel as he emerged exhausted from the bath, or perhaps the shower, a Supreme Court justice. She was “as dear and close a human being as I could have ever imagined having in my life.” They had been through a “fiery trial” and emerged “one being — an amalgam.”

3.

Things About Our Country

It wasn’t normal for the wife of a Supreme Court justice to give a full, intensely personal, and aggrieved account of the confirmation process and her husband’s attendant breakdown to People magazine, complete with posed pictures of them in their apartment — here casually reading a Bible together on the couch, here drinking coffee in the kitchen, here holding hands amid a bunch of binders on the floor — but from the very beginning Ginni and Clarence Thomas would appear to have no particular interest in decorum. In 1994, Clarence Thomas, successor of Thurgood Marshall on a Court steeped in “formality, courtesy, and dignity,” according to its Historical Society, presided over and hosted Rush Limbaugh’s third wedding, to a former aerobics instructor he met on CompuServe, at the Thomases’ home in Fairfax Station. Thomas had told the nation he couldn’t get his reputation back; he evidently did not care to try.

He stopped reading the newspaper. Their new home was invisible from the street. Clarence did not want more children, and Ginni had to accommodate this choice. It was her idea that they take in Clarence’s grandnephew, whose father was in prison; actually, she would have taken in all three siblings had their mother allowed it. They did not enter the broader social life of D.C. available to Supreme Court justices; they never would. The hearings confirmed something Clarence had long suspected. Southern racists were rattlesnakes. At least you heard them coming. “You know,” Clarence said, “where they stand.” New England liberals were water moccasins; just as deadly, and silent until they struck. He preferred people who didn’t smile through their hatred.

And yet Ginni’s new life as political spouse entailed precisely this, smiling as she met people for whom she felt only revulsion. “Wow,” she told The Wall Street Journal after she met Hillary Clinton, “now I have to, in my role, be respectful and cordial and courteous.” She seemed to have given up on the idea of being a representative for Nebraska. “I’m kind of stuck here,” she told the Journal, but there was lots one could do to further the cause in D.C. One could, on behalf of two House Republicans, send out a memo to House committees asking for “examples of dishonesty or ethical lapses in the Clinton administration,” a memo so objectionable in its stark partisanship that Democrats blew it up and posted it on an easel. During a hearing on a Clinton ethics controversy, Virginia Democrat Jim Moran openly objected to the presence of “Mrs. Clarence Thomas in that bright-blue dress.” Later that day, in an elevator, Ginni showed Moran a recently published book called Everything Men Know About Women. The pages of the book are blank. “This is about you,” she said.

Another man might have been embarrassed. Clarence called his wife at work and sang verses of “Devil With a Blue Dress On.” “Troublemaker” was what she called herself, a puckish spin on her decadeslong habit of creating the appearance of corruption. “Did the Missus Go Too Far?” read a typical headline in the Chicago Tribune. The missus did not go too far, she later said, because she was in the “political lane” and he in the “legal lane.” “I kind of zone out when it comes to legal issues,” she told the January 6 committee, perhaps the most relatable thing she has ever said. They simply would not talk about it.

They wouldn’t talk about it, specifically, in their used 40-foot Prevost motor coach, purchased in 1999 and taken to two dozen states in these two decades. The motor coach in which they did not discuss work was their favorite subject of conversation. (“Anybody ever tell you you look like Clarence Thomas?” he was asked at a Flying J.) This was the public identity they would allow, and it was not inaccurate: a couple who adored the company of one another making camp in RV parks in Michigan as relief from the stress of Washington. That the Thomases’ appreciation for middle-class travel is useful PR does not make it untrue, but as with all PR, something goes unsaid. They did not, neither in myriad public fora nor in legally required paperwork, mention various travels by yacht and private jet.

Harlan Crow, the Republican activist and billionaire son of a man whose company Forbes once called “the largest landlord in the United States,” says that he and Clarence Thomas share an interest in the virtue of “humility.” He and Clarence are good friends — even better friends than Harlan is with George W. Bush, he says — which explains the jet, and the yacht, and the $19,000 Bible once owned by Frederick Douglass, and the 1,800 pounds of bronze cast in the shape of Clarence’s favorite teacher and placed at a cemetery in New Jersey. Harlan Crow bought Thomas’s mother’s house, installed a gate and fixed the roof, and allowed her to continue living there. Clarence sent his adopted grandnephew to private school, and Crow paid roughly $100,000 in tuition; the president of a group of RV enthusiasts paid for $5,000 more. There was $150,000 to rename a wing of the Savannah library, another $105,000 to have him commemorated at Yale, millions on a museum in Pin Point. Ginni Thomas started a consulting firm with $550,000, $500,000 of which had been Harlan’s. In a Washington Examiner story celebrating Clarence’s Everyman RV trips, Clarence is pictured beside his motor home, wearing what reporters at ProPublica discovered to be a custom polo shirt Harlan Crow gifted guests on luxury vacations. Twenty times he failed to report Ginni’s income.

Harlan Crow is an early donor to Club for Growth, on the board of the American Enterprise Institute, married to someone on the board of the Manhattan Institute, all organizations that provide comforting intellectual justification for the class into which he had been born. It is Crow’s contention that he and his “quite close friend,” really his “brother,” share a “worldview,” which is extremely unlikely given that from the bench, Clarence Thomas continued to center Black experience. As Corey Robin points out in his extraordinary book The Enigma of Clarence Thomas, Thomas’s position was typically that white racism is immutable and white plans to improve Black life poisonous.

In 2003, eight justices agreed that a Virginia law treating cross burning as evidence of an “intent to intimidate” was in violation of the First Amendment. Thomas alone argued that cross burning was equivalent to a physical threat and not constitutionally protected; though the implications might be unclear to “outsiders,” by which Thomas surely meant his white fellow justices, such an act was always in the American context an act of racial terror. In a 1992 case, the court ruled against white defendants, accused of assaulting Black victims, who wanted to strike potential jurors due to race; Thomas alone pointed out that Black defendants might want to exclude their own jurors. The other justices who continue to be skeptical of affirmative action focus on students who are not admitted to their preferred schools, whereas Thomas singles out the experience of the worthy Black student who is admitted but “tarred as undeserving” by his peers.

Thomas quotes W.E.B. Du Bois and Frederick Douglass, he echoes arguments one might encounter in Black Power, he draws frequently on his own painful childhood, and yet he comes, almost all of the time, to conclusions amenable to Harlan Crow. In an opinion on affirmative action and elsewhere, Thomas quotes Douglass: “The American people have always been anxious to know what they shall do with us … I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us.” It would be madness to suggest that Clarence was wrong to see hypocrisy, condescension, and white supremacy running through the progressive project, and while these may not have been the concerns of his friends in Washington, he found in Republicans people with the same basic program: to take, when confronted with a neighbor’s deprivation, no political action at all.

“Do nothing with us,” Douglass had said. But then, Clarence did not do nothing. He sided overwhelmingly with the carceral state. Thomas cared less than any of his fellow justices about the constraints of precedent. He sided with states actively managing the map to destroy Black voting blocs. He did not in fact share Crow’s worldview, but he had melded a mix of Black nationalism and originalism sufficient to build a decoy.

“I think it’s very hard,” Harlan Crow once said, “to reconstruct how did you become what you are.”

There was something in Ginni and Clarence that reinforced and refined a shared extremism, something beyond their shared intolerance for ambiguity. There was an interlocking set of beliefs, a fatalism born of the lived experience of racism and the entire heavily manned edifice of white ignorance. If white liberals only made anything worse, if they would sacrifice the safety of children sent into South Boston in service of their own pathetic vanity, they might as well live inside their own self-affirming stories. They were most dangerous, after all, when they tried to help. They were most supportive, those angels lining the hallway, when you left their myths intact.

On the day George H.W. Bush nominated him, Clarence Thomas gave a brief speech of acceptance. “Only in America,” he said, though those weren’t his words. They had been added, just before, by his wife.

4.

Windmills

It’s so exciting to be with you guys!” Ginni Thomas told the Turning Point USA teens in 2016. “Gosh, I’m so excited. Life is filled with inspiring people, have you found that in your life? And look at how you dress! Oh my gosh!”

Ginni Thomas often seems, in her public appearances, a little lost, veering in the span of 20 minutes between limp applause lines (“Where are my tall people? I love you tall people”), anecdotes of questionable origin (“The marines should not be wearing high heels”), and suspect controversies she has done nothing to set up (“150 homosexuals who didn’t want Jerry Boykin to teach anymore”). And yet there is a true north — the enemy — that always brings her home. “Be Happy,” says Ginni Thomas’s public Facebook page. “It Drives the Haters Crazy!” Once, Ginni says with pride, she was gifted a platter that read MAY ALL THE BRIDGES I BURN LIGHT THE WAY. In October 2018, Ginni Thomas was publicly complaining about a sign at her vet’s office that said SPREAD KINDNESS, interpreting it, probably correctly, as an attack on her way of life.

There was a way Republicans spoke prior to the tea party, and a way after, the latter being more suited to Ginni’s impulses. She spoke at tea-party rallies; her favorite rhetorical move involved recognizing you, the activist, the “troublemaker,” the only one who could be counted on to engage her list of “action items.” She had thrown herself in with Trump, regularly haranguing the man to hire people unemployable even by his administration’s standards. And as with Trump, there were certain fixations. “I would love you to consider an apology sometime and some full explanation of why you did what you did with my husband,” began the message left at a bracing 7:31 a.m. on Anita Hill’s voice-mail box, 19 years after the hearings. “So give it some thought and certainly pray about this and come to understand why you did what you did … Okay, have a good day.” Twelve years after that, Ginni was still hoping Hill would one day ask “for forgiveness.” She figured it was bound to happen. “Sooner or later,” she said optimistically, “lies catch up with you.”

There is considerable ambiguity about what various participants in the invasion of the Capitol on January 6 were doing. There is no ambiguity about what Ginni Thomas was doing. She was trying to overthrow the government. Biden had been elected on November 3. On November 5, Ginni seemed to think everything had been taken care of. The “Biden crime family & ballot fraud co-conspirators,” she wrote in a text to the president’s chief of staff, “are being arrested & detained … & will be living in barges off GITMO to face military tribunals for sedition.” On November 9, she sent dozens of Arizona lawmakers emails asking them to choose their own electors (that choice being “yours and yours alone”) rather than let Biden take the state he had won. “Help This Great President stand firm, Mark!!!,” she wrote to Meadows the next day. “You are the leader, with him.” November 19: “The intense pressures you and our President are now experiencing are more intense than Anything Experienced (but I only felt a fraction of it in 1991).”

Here she had been obsessing this whole time, and here now, three decades after the hearings, ten years after the voice-mail, the very old man who presided over the hearings had come back to thwart her. Of course it was connected. Virginia Thomas speaks the language of QAnon, but her texts to Meadows lack the coherence of even a sophisticated QAnon adherent; they are, according to the hosts of the podcast QAnonymous, redolent of “the classic QAnon boomer” whom younger, more-with-it followers of Q would kick off boards for theories “too stupid and melted.”

On January 6, she posted a George Orwell quote to social media. The quote was fake. She was a Facebook-addled 63-year-old woman posting at 3:33 a.m., 3:46 (“I get up early with my dogs,” she told the committee), whose sources of information included Glenn Beck and other more obscure because more insane right-wing conspiracy theorists. She was a woman who identified happiness itself as an act of antagonism against “haters,” a self-proclaimed bridge burner disgusted with both Mike Pence and “elites,” a category that evidently did not include the wife of the longest-serving Supreme Court justice or the president’s chief of staff to whom she happened to be talking. She was a hype-woman being hyped up by her friends (“There are no rules in war,” Connie Hair, then Louie Gohmert’s chief of staff, reportedly texted her) and in turn hyping others. She was picking up “vibes,” she told the January 6 committee, vibes being sufficient basis on which to overturn an election.

“And then the one other thing,” Ginni Thomas told the Turning Point USA women, concluding her description of the charm bracelet. “A windmill.”

“We both tilt at windmills,” Clarence had told her, an allusion to Don Quixote with precisely one meaning: to attack imaginary enemies.

“Oh,” said Ginni. “Well as long as we both do it.”

As long as we both do it. Over the course of his career, Thomas has recused himself for cases involving Jamal’s college and workplace. He has never, despite much criticism, recused himself regarding anything involving Ginni. In January 2021, the Supreme Court released a four-page ruling denying the Trump administration’s request to prevent Congress from obtaining various documents related to January 6. The ruling included a single public dissent: Justice Thomas would grant the application. It remains extraordinary that Thomas would neither recuse himself, nor, alone among nine justices, deny the assertion of executive privilege.

There is no obvious strategic benefit toward making a spectacle of one’s lack of respect for judicial procedure. This is not useful to the Federalist Society, or to Harlan Crow, or to the many institutions Harlan Crow supports. It is an expression of love to Ginni, or an expression of disdain for the rest of us, or both.

“What’s the best part of being a justice?” she asked him in their interview.

“First of all,” he said, “it would be impossible without you … Um, it’s sort of like” — and here he is searching for the words, his eyes darting back and forth — “it’s sort of like, How do you run with one leg?”

Clarence Thomas has served for more than 31 years, longer than any of his fellow justices. Eight times, then, he has watched hearings in which his future colleagues swear fealty to objective jurisprudence rather than personal prejudice. “We don’t turn a matter over to a judge because we want his view about what the best idea is, what the best solution is,” John Roberts said in 2005. “I don’t judge on the basis of ideology,” Sonia Sotomayor said in 2009. Across law schools and among centrist opinion writers, this particular mythos survived the spectacle of the Brett Kavanaugh hearings (“A good judge must be an umpire, a neutral and impartial arbiter”) and through the procedural improprieties of Amy Coney Barrett’s rushed confirmation, wherein she described her job as “going where the law leads.”

It took a lot, is what I am saying, to sweep away this fantasy, to drive the Court’s reputation to its historic low. It took a reckless extremism, the open rebellion of a man showing you his used motor home in his custom yacht polo. It took the marriage of a Black man’s not unjustified fatalism with the boundless white impulse to build walls against unpleasant knowledge; what the late philosopher Charles Mills called “the management of memory.” It took the marriage of a man who needed adulation as shield against self-doubt and a woman who needed a guru to shield her from ambiguity. It entailed the tribal pride of a little girl in a patriotic sash and the agony of a little boy who just wanted to open a second fucking box of cereal.

If there is anything that holds together Clarence Thomas’s belief system, it is a not unsympathetic preference for clarity. Anyone who has experienced discrimination knows what it is to prefer the transparency of open hostility to the obfuscations of condescension and sanctimony, the rattlesnake to the water moccasin. Self-satisfied liberals can confuse their own interests for yours. Affirmative action is messy. Precedent clouds the apparent clarity of the Constitution. Sometimes you just want the subtext to be made text. It is in this spirit that we can appreciate the Thomases’ insistence on revealing the true nature of the nation’s most mythologized judicial institution. The Supreme Court is a political body composed of political actors. In five years’ time, Clarence Thomas will be the longest-serving justice in American history. Harlan will continue to print up custom polos. Ginni will still be waiting for Anita Hill’s apology. And far fewer of us will pretend the Court is constrained by anything but the wild, emotive whims of imperfect people. It’s a gift, at long last, from them to you.

*Correction: This story has been updated to more accurately reflect Edward P. Jones’s relationship to Clarence Thomas.