This article is a collaboration between the Columbia Daily Spectator and New York Magazine.

On April 30, armed police officers swarmed the Columbia University campus for the second time in two weeks, shutting down a student occupation of Hamilton Hall and clearing what was left of the Gaza Solidarity Encampment. Students had first seized part of the South Lawn, then the attention of the entire Columbia community, and then the national political narrative, as imitation protests in support of Palestine erupted at colleges across America. By refusing to leave unless Columbia committed to divest from Israel and cut ties with Tel Aviv University, among other demands, the students were acting in the shadow of 1968, when protesters dramatically took over buildings, including Hamilton, to resist the Vietnam War and the university’s racial politics. Those events established Columbia’s reputation as a hotbed of dissent where social and political change takes root before spreading to the rest of the country — often at great cost to the institution. As the school itself notes about ’68 on its website, “It took decades for the University to recover.”

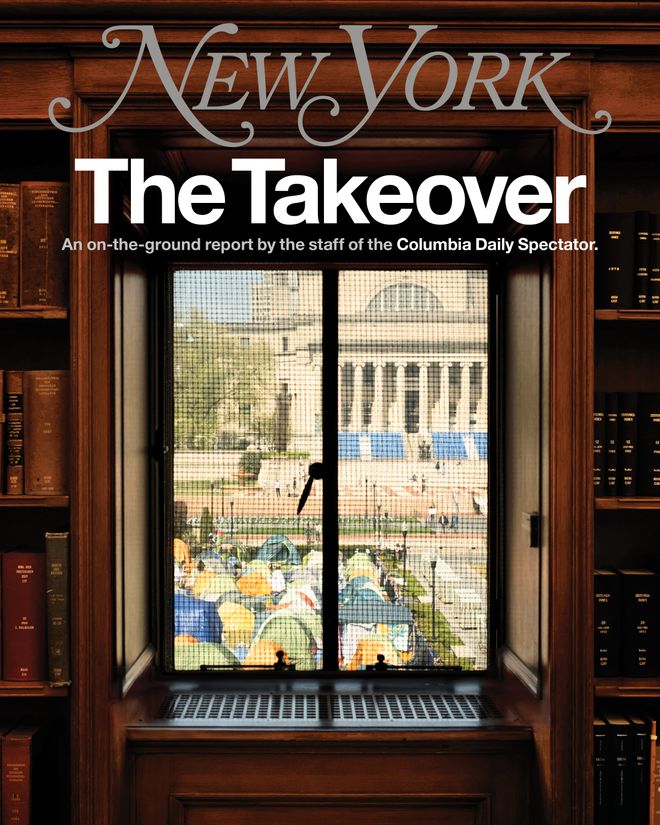

Cover Story

The encampment and the takeover of Hamilton represented a dramatic escalation of months of activism on campus. Since the October 7 attack on Israel and its subsequent war in Gaza, which has killed more than 34,000 Palestinians, the school has been the site of intense protests and counterprotests with bitter debates on campus over antisemitism and Islamophobia, genocide, and free speech. Overseeing it all was a new president, Minouche Shafik, whose inauguration had come just three days before 10/7 and who had scarcely begun to acquaint herself with the Columbia community when the campus was thrown into crisis. With national political figures and billionaires agitating for the removal of other Ivy League presidents, Shafik was charged with resolving standoffs among groups with vastly divergent interests: deep-pocketed donors used to getting their way, faculty with the security of tenure, and students who believe Columbia is betraying its legacy as an engine for progress. As the encampment impasse played out, it became clearer than ever that people were living in two different Columbias. As pro-Palestinian protesters built a community of hope and solidarity around their support for Gaza, many pro-Israel students reported feeling unwelcome and organized their own counterprotests on and around campus. Some of the latter group packed their bags and left, while many of the former were hauled off to jail and suspended.

The staff of the Columbia Daily Spectator, the nearly 150-year-old undergraduate newspaper, has been covering every minute of this story. Recently, New York Magazine asked us to create this report, leveraging our intimate knowledge of the university and its people to tell the story from the inside. Our reporters, writers, editors, and photographers polled more than 700 Columbians to better understand what happened, took more than 100 portraits of members of the community, and compiled this oral history of the two weeks that forever changed our university. —Isabella Ramírez, editor-in-chief, Columbia Daily Spectator

The First Encampment

Mid-April at Columbia usually represents the homestretch of the academic year as students finish their classes, cram for finals, and take study breaks on the lawns. Meanwhile, the staff prepares the grounds for Commencement. On the morning of Wednesday, April 17, Shafik was in Washington, D.C., scheduled to address Congress about antisemitism on campus. Hours earlier, in the dead of night, pro-Palestinian students began executing plans to occupy the school’s South Lawn.

Laura, a senior: It’s so hard to be here and to know that the tuition I pay is going to fund the genocide in Gaza. I’d been doing marches and protests all year in solidarity. But there was never a moment where I felt hopeful. Like, Joe Biden’s not going to care. And then — hearing that there was this escalation planned — it was like, Okay, we could be in a situation where we suddenly have negotiating power.

The planning was super-confidential. If you wanted to let someone in on it, you had to swear them to secrecy, one-on-one. I went to my professor’s office, and I was like, “Put your phone on airplane mode. Disconnect from Wi-Fi. This is what’s happening.”

Liam,* a junior: For me, joining was a bit of an impulsive decision. I was like, I just need to do it. I take out $50,000 in student loans every single year, and it sucks. I have to work 20 hours a week to pay off the interest. I hate sitting here knowing I’m working my ass off only so my money can go to supporting genocide. It boiled down to my integrity — we are the students of this school, we are their funding.

K., a senior: I had learned so much about the precedent of organizing at Columbia and understanding that we have this massive history of protests and that there are all these eyes on us. I have so much privilege being here. I’m from a first-gen, low-income background. So I knew that if there was ever going to be an escalation, it was something I wanted to be a part of. I consulted a lot of my friends about it, and at first a lot of us were questioning whether this would be a fully planned, well-thought-out action, which in hindsight is ridiculous. It was incredibly well planned. And it made sense that they had to withhold certain information for safety and security.

Laura: I finished my thesis on Tuesday and then I threw up because I was so nervous. I spent the day emotionally preparing. I had some friends who were going in with me, so that night we met at my apartment, packed our bags, and went to campus around 1 a.m.

K.: At first, all we knew was that we were occupying some part of Columbia. Even on Tuesday morning, there was no set location we knew about. I just assumed, Oh, for history’s sake, let’s occupy Hamilton, great, let’s camp out in the hallway. We’re gonna have a slumber party. I had no idea it was going to be an actual camp.

Columbia’s policies forbid political demonstrations. Students gathered at various points around campus with their gear, trying not to arouse suspicion, and waited until it was time to move to the South Lawn in groups they called platoons. The campus gates at West 116th Street on Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue were wide open.

K.: We were all sitting in a circle on the lawn wearing black. And we’re just like, “There’s no way Public Safety’s not going to come up to us and ask, ‘What are you doing?’ ” I don’t believe you can bring all these supplies onto the main lawn without getting stopped by security. My friend and I were joking, “What’s our cover story? Maybe we’re the Barnard Outdoor Adventure Club.”

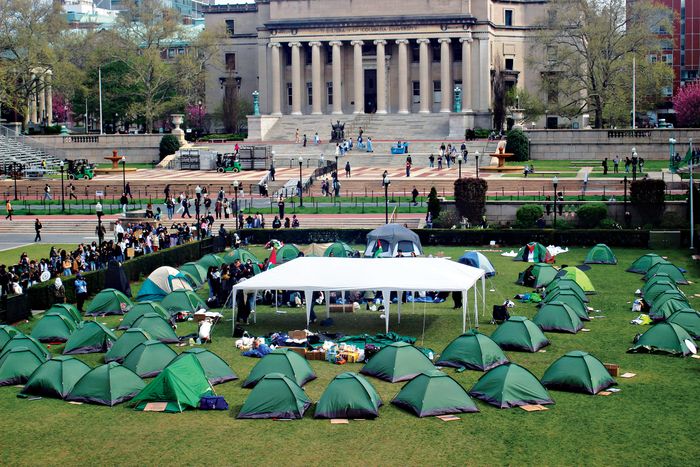

Laura: It was so smooth and well coordinated. We immediately started pitching tents, and within 20 minutes, it felt like there were 40. It was really unbelievable.

K.: At some point, they started assembling the first big white tarp. It was really cute because it’s just a bunch of college kids trying to pitch a big-ass wedding tent.

Steven,* a junior: The organizers started to put together community standards for the camp and a governing structure, in terms of like, “We’re meeting twice a day at these times.” It was clear they knew how essential that was for the camp to continue. We took a vote on Wednesday night on whether to continue the encampment. And it was unanimous.

K.: We racked up so many food donations it was ridiculous. We started organizing all the food stuff because it was slowly coming in a bunch of carts: Costco hummus, Honey Nut Cheerios, fruit, granola bars, Dunkin’ Donuts coffee, soy milk. I was like, “At least they have alternative milk.” And then they said we had a camping toilet. I’ve seen those, and this was not a camping toilet. It wasn’t even a bucket. It was like a bucket with no bottom, and it had a little lip thing and these little black trash bags that you put on there. You would do your thing, and there were poo gels to make it smell better. And then you would close up the bag and throw it in the bigger bag of everyone’s shit.

Steven: I missed a lecture on Wednesday about literature and cultures of struggle in South Africa. I was outside of my tent, and I heard my name. So I went to the fence and two students from the lecture that I’ve never talked to called me over and they were just offering to, like, bring me food or whatever I needed. I obviously asked about class, and they said, “You didn’t miss anything.”

In Washington, Shafik began testifying before the House Committee on Education and the Workforce at about 10:30 a.m. The hearing’s title: “Columbia in Crisis.” Two other Ivy League presidents, Harvard University’s Claudine Gay and the University of Pennsylvania’s Liz Magill, had appeared months earlier and flubbed a question about whether calls for genocide against Jewish people were against their universities’ policies. Both had to resign. Determined to avoid their fate, Shafik spoke hawkishly, detailing disciplinary actions she had taken against students and sharply criticizing members of her faculty.

Stacy,* a professor: The terms of the questioning were just completely false. The question of whether or not Columbia is willing to protect its students against antisemitism has very little to do with whether students who are concerned about genocidal military tactics should be able to speak about that publicly. Those are two separate issues.

Adam Tooze, a professor: I realized, Oh dear. This is how she is going to cope with this? What is her response going to be? It turns out to be a technocratic hard line.

The students’ occupation of the South Lawn overshadowed Shafik’s testimony and became the center of attention on campus — as did the organization behind it, a coalition of more than 100 student groups known as Columbia University Apartheid Divest, or CUAD. While students who opposed the war in Gaza were galvanized, many pro-Israel students continued to bristle at the protesters’ use of slogans like “From the river to the sea” and “Globalize the intifada.”

Henry Sears, a senior: I had a lot of complex feelings around the encampment. I support their right to free speech. However, some of the speech we were hearing out of there was really horrible.

Rachel Freilich, a freshman: About that time, when I would walk around campus, I would tuck in my dog-tag necklace, which says BRING THEM HOME. I wouldn’t really walk around with a Magen David — a Star of David — necklace, either. I didn’t want to get harassed. I didn’t want to get hurt. And I don’t want my professors to profile me because I’m a Zionist. It felt like I had to hide an integral part of who I am.

Parker De Dekér, a freshman: As President Shafik was testifying about the implications of antisemitism, ironically, antisemitism was rapidly increasing at a rate I had never seen before on our campus. I don’t mean the protesters sitting on the lawns. Them sitting there and exercising their rights to free speech and advocating for peace in the Middle East is not antisemitism. What is antisemitism, though, is the numerous experiences I’ve been faced with. Wednesday evening, I was walking from my dorm to go to Chabad, a space for Jewish students at Columbia, and someone yells, “You fucking Jew, you keep on testifying, you fucking Jew.” I had clearly not been in Washington, D.C., that day testifying. I was not involved in anything political. I was simply a Jewish student wearing my yarmulke.

The First Arrests

The more than 100 individuals occupying the South Lawn understood there would likely be significant consequences from both the university and the police. On April 18, Shafik suspended all of the students and authorized the NYPD to enter Columbia’s private property and clear them out. Early that afternoon, dozens of officers, many wearing riot gear, began their sweep. Hundreds of onlookers watched the largest mass arrests at Columbia since 1968.

Laura: I’m a senior; I’m supposed to graduate. I’m also a low-income student. A lot was on the line. My parents had been sending all these messages: “Please leave. You can’t afford to be there.” I’m really close to my family, so it was heartbreaking: “There’s other students there who have so much money, and that’s not you.” And “I’ve worked so hard at so many jobs for you to go to this school, and now you’re throwing it all away.” And “This is not going to matter. You being there or you being outside doesn’t make a difference.” But I asked myself, What am I willing to give up? If people in Gaza can keep giving up everything, it’s not a big deal to be arrested for a few hours.

K.: We had been briefed on what to do if we got swept by the police. The plan was to form two concentric circles: people of color on the inside, white people on the outside. We were informed that it’s harder for cops to arrest you if you’re sitting. So the plan was, once we knew cops were coming, to sit in your circle.

Laura: It was really emotional to be sitting in the circle with all these people — some of them my friends and some I barely knew. But we’re all holding hands. The person next to me and I were holding hands really tight.

K.: The cops had that big-ass annoying speaker blaring, “If you do not get up, you will be arrested.”

Steven: I was taken with another person who was crying a lot. And as we were walking out, our arresting officer was like, “Oh, it’s just summonses,” which I thought was so weird because it was his attempt to comfort us, right? It’s almost this admission that you have some awareness that what you’re doing is wrong.

K.: Our arresting officer was trying to make small talk. She was like, “Come on, guys. You can talk to me. I’m also just a person.” Then she goes, “But you guys know it was your president who told us to arrest you?”

The arrests shocked nearly everyone at the university and intensified national scrutiny of Shafik’s handling of the protests. Now under suspension, the arrested students found themselves alienated from campus. Some were placed under a strange kind of house arrest: They could remain in their dorm rooms but could lose access to housing if they left. Students at Barnard, who are subject to a different disciplinary process, were evicted from college housing and lost their access to campus dining. (Within days, Barnard reached agreements with most students to end their suspensions and allow them back on campus.)

Henry: The arrests were difficult to watch. Even though these were people who I very much disagreed with on many things, it was hard to see them, my fellow students, carried off campus by the NYPD.

Elizabeth Ananat, a professor: The students were left homeless in New York City. I never thought that I would be part of an organization that causes people to be on the street in the middle of the night. It was such an unnecessary cruelty and a betrayal of everything.

Soph Askanase, a junior: Barnard loves to tout itself as a progressive institution that builds student activists, leaders of the future. They love to talk about the incredible organizer voices that have come from the university in the past, yet this is how they’re treating the organizers on this campus now.

The Pro-Israel Protests

Shafik’s decision to call in the police was widely understood to have backfired, and pro-Palestine students at colleges from California to Florida began to organize campus occupations that would follow Columbia’s lead. Meanwhile, in Morningside Heights, some who considered themselves pro-Israel were now sympathetic to the arrested students — while many others felt reassured by the university enforcing its existing policies. Jewish students reported numerous instances of antisemitism both inside and outside the campus gates, and pro-Israel students organized demonstrations of their own. One protest, at Butler Library, had been arranged prior to the encampment; another took place at the Sundial, a popular meeting place at the center of campus. The biggest, the United for Israel March, happened outside the gates and was organized by conservative media figures. Multiple students reported instances of racist and Islamophobic harassment from protesters.

Chloe Katz, a junior: One day at noon, we stood in front of Butler Library. We had authorization. We put duct tape over our mouths to represent the women who are being silenced in the media and on campus when they express what happened to them or people they know — the horrific sexual violence that occurred. We linked arms and had signs saying RAPE IS NOT RESISTANCE and HAMAS WEAPONIZES SEXUAL ASSAULTS. We were near the encampment, and soon after we began, they began their own protest. They were chanting things like “Glory to our martyrs” and “Globalize the intifada.”

Rachel: We went to the Sundial protest on Saturday night, and we were playing Jewish songs. We replayed this song “One Day” probably 20 times, just a song of peace. And as we were singing, people were just chanting at us and screaming slurs. In the moment, I didn’t think that I was in danger — I was just surrounded by so many people and so proud to be a Jewish person on campus. But when I got back to my room, I sort of broke down. I was just like, Wow, I was really in danger.

Chloe: When I saw that people were organizing a counterprotest, I immediately wanted to join. But my father said, “Please don’t go, I don’t think it’s safe.” And unfortunately, he was 100 percent correct. What I saw from the videos is my friends expressing their opinions, singing peaceful songs, holding up Israeli and American flags — and they had water thrown on them. There was an attempt to burn an Israeli flag. One of my friends was surrounded.

Eve Spear, a senior: I saw a video of a student holding a sign that read AL-QASAM’S NEXT TARGETS, pointing at Jewish students — my friends. When I got there, one individual was leaning forward, taunting my friend to his face, and I started videoing because I thought my friend was going to get punched. You need proof — it would be hard enough to say that this happened. They were screaming at us: “You fucking inbreds,” “Uncultured ass bitches,” and “All you do is colonize.”

When we walked off campus, a new person screamed at us, “Go back to Poland!” I was physically shaking. We had one student who is six-five, and he made sure we all crossed the road, but neither Public Safety nor the NYPD ensured our safety. We all had to make sure one another got home safely. I live in the dorms and we have campus security there and usually I don’t lock my door. That was the first time I was like, I need to lock my door. I was worried: What if people are following us? Saturday night was antisemitism in its most blatant form.

Lily,* staff: I consider myself Jewish. When I’ve been on campus, I have felt uncomfortable with the things some pro-Israel protesters are saying, but I have not felt unsafe. What I keep seeing is the conflation of not being comfortable with being unsafe, and I think it’s kind of a cop-out for the university to say this is about antisemitism. My opinions on the college really changed when pro-Palestine protesters were sprayed with a chemical. If it had been the Jewish or pro-Zionist students that were sprayed, we would be in a very different timeline.

The Second Encampment

The South Lawn has two grassy fields, and at the first encampment, protesters had occupied one of them. Immediately after their arrests, as Columbia staff were dismantling their tents, hundreds of other students crossed a fence onto the other patch in a show of solidarity.

Laura: It was autonomous and spontaneous. There was no organizing. They just jumped.

Sueda Polat, a graduate student: The university’s response galvanized people in a way that was surprising even to me as an organizer. I remember running through the crowd trying to find friends, a megaphone. I’m trying to corral people into doing something that they previously didn’t know they would be doing. We jumped the fence and it felt like we were crossing a line that we couldn’t come back from.

Liam: When I was sitting in the van going down to 1 Police Plaza, I’d been thinking, Man, we fucked up. We’ve been arrested. It’s over. Then coming back and getting on campus and seeing that it had been reinstated — it was almost a feeling of incredulity. People really want to do this again? We literally just got hauled off — aren’t you risking the same thing? And obviously, the answer was unanimously “yes.”

Jared, a graduate student: They arrested a hundred people, and a thousand more sprang up in their place. People were sending food from all over the world. They donated on Venmo. Alumni showed up with supplies and blankets. An organization brought a bunch of meals to Earl Hall, and I was running back and forth. It took like three trips to bring everything in.

The second encampment would remain for days to come. The situation was something of a standoff: Shafik seemed to indicate that she would not call for the police again, and while the protesters engaged in negotiations with her administration, the university made no major concessions. Campus life went on: Members of the faculty held teach-ins on the lawn, a weekend for admitted high-schoolers came and went, and Jewish students celebrated Passover. Meanwhile, Columbia became a magnet for high-profile politicians, including Representatives Ilhan Omar (whose daughter Isra Hirsi had been arrested and suspended), Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Virginia Foxx. The Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, was booed while giving a speech on campus condemning the protests and telling students to “go back to class.”

Elizabeth: To watch Mike Johnson describe students as overprivileged when so many of our students are first-gen or low income and are doing things at great risk to themselves — to have that treated as if they are coddled was offensive and infuriating.

Aharon Dardik, a sophomore: The Friday night prayers, Kabbalat Shabbat, in the encampment were beautiful. There was a real sense of community and resilience — and attempts to fuse the love and joy of Shabbat with being in the encampment even in the face of oppressive forces.

Jillian, an undergraduate: We had dabka lessons, which is a Palestinian dance. We had the People’s Library for Liberated Learning. There were books in there we could check out. A main takeaway for me was applying the learning I’ve done in my own classes, where we have talked about transnational movements against imperialism, capitalism, colonization. There was a really strong understanding that all of these struggles were intertwined.

Sueda: It’s important to realize how grounded we are in Palestine. I see Palestinian journalists who are my peers, the same age as I am, who have had their universities destroyed, demolished by the occupation forces, send us tweets saying they’re proud of us — when we’re in a relatively safe area, nothing in comparison to the genocide they’re facing. It reminded us that we can’t stop.

Jude Webre, a lecturer: National media outlets have already written the narrative of what’s going on, and they’re not interested in understanding the position of the protesters on the inside. So they report more on what’s happening outside the gates, which is a different thing. In my mind, the problem isn’t the young people on the inside; it’s the adults on the outside who really escalated the situation because of their own preconceived notions of what’s going on.

Jared: I made the decision to skip my family’s Passover and go to the Passover Seder in the encampment because I kept seeing stupid-ass people online talking about how this movement was antisemitic. To me, it embodied the spirit of Passover, which is the liberation of oppressed people.

The claim that “outside agitators” were fomenting unrest, made by Eric Adams and others, fueled anxiety among many pro-Israel Jewish students. On April 21, a campus rabbi wrote to nearly 300 Jewish students telling them to leave campus for their own safety. The university also announced that students could attend classes virtually in order to avoid campus and “deescalate the rancor.” Columbia administrators barred a prominent student protester, Khymani James, from campus after strikingly violent remarks he had made on social media — including “Be grateful that I’m not just going out and murdering Zionists” — resurfaced and went viral.

Shiri Gil, a junior: At this point, I’m not saying I’m Jewish, I’m not saying I’m Israeli. I’m barely on campus because I feel threatened. My friend was called a Nazi and physically pushed off the lawn where the encampment is — a space where everyone can be, a public place for everyone.

Parker: If you are a Jew who has any level of support for Israel, then you’re not welcome in progressive circles. In the lobby of my dorm, I ran into a Jewish student who was leaving. He was flustered and frantic and had a whole bunch of things that he needed help with. And as we’re trying to get his stuff out of the Lerner Hall turnstile to get out to Broadway, where his father is picking him up, people are beginning to stare at us and getting visibly upset. And they say, “We are so happy that you Zionists are finally leaving campus.” And another student goes, “You wouldn’t have to leave if you weren’t a supporter of genocide.”

One morning, I was walking out from the Amsterdam gate to an Uber, and this individual on the street yells at me and says, “Keep on walking, kike.” The hardest thing about it — I don’t think he was a student. He looked like a fully grown adult. I really do appreciate that there are members within CUAD who are advocating for students not to have to go through this, who say this doesn’t represent their movement. That’s important to me. The saddest thing is our university isn’t standing up for its Jewish students.

Rachel: I left campus Sunday afternoon. I just couldn’t be there anymore. I didn’t feel safe. I had seen videos of people sneaking into campus through the gates. We didn’t know what was coming into campus — we didn’t know what was in their bags, we didn’t know who these people were. And people were already getting violent outside the gates, screaming “Yeah, Hamas” and “Burn Tel Aviv to the ground.” A lot of family members have told me that I should transfer. But realistically, I’m not going anywhere. It’s very important to stand our ground and show them they can’t force Zionist Jewish students out of their campus.

Ege Y., a lecturer: I am a Muslim faculty member, and I’ve definitely not felt welcome as a Muslim. Provocateurs have approached faculty as we linked arms to protect our students from harassment. They called us supporters of terrorism. I also know colleagues who have been doxed and who’ve been threatened by their own students.

Rebecca Kobrin, a professor: There’s this narrative that it’s all anti-Israel and no antisemitism. And there’s this other narrative that it’s all antisemitism and none of it is about Israel. And I believe that we just have not modeled listening to each other.

Henry: I think it’s important to highlight that while Jewish students definitely feel less safe on campus, it’s not just us. There have also been actions against Muslim or pro-Palestinian or Palestinian students. We’re all having to deal with this horrible campus environment.

At the General Studies Gala, I saw a bunch of students who had their keffiyehs ripped off and were called “terrorists,” “sluts,” and “whores.”

The Takeover of Hamilton Hall

In negotiations with the protesters, Columbia floated modest changes to its policies, including greater transparency on investments, and offered to fund health and education efforts in Gaza, among other proposals. But the students wanted nothing short of full divestment from Israel. On April 29, Shafik announced that the talks had failed and gave the students a deadline to disperse — or else face consequences more serious than before. Members of CUAD voted to stay put.

Sueda: The process of negotiations — no matter how much the university claims it was in good faith, it was not. We were also being surveilled by the university. We were told that the rooms we were caucusing in were bugged as well as the room we were negotiating in. On several occasions, we were followed. It felt like we were in a movie.

With the deadline expiring at 2 p.m., hundreds picketed around the South Lawn, chanting, “It is right to rebel. Columbia, go to hell.” With no apparent move by the university to clear the camps, things were relatively calm until just before midnight. In the early hours of April 30, a new encampment formed on the lawn in front of Lewisohn Hall with at least a dozen tents; students climbed Alma Mater, the iconic statue at the center of campus, to wrap her neck with a keffiyeh; and there was more picketing. Suddenly, dozens of the picketers broke from their line and charged toward Hamilton Hall.

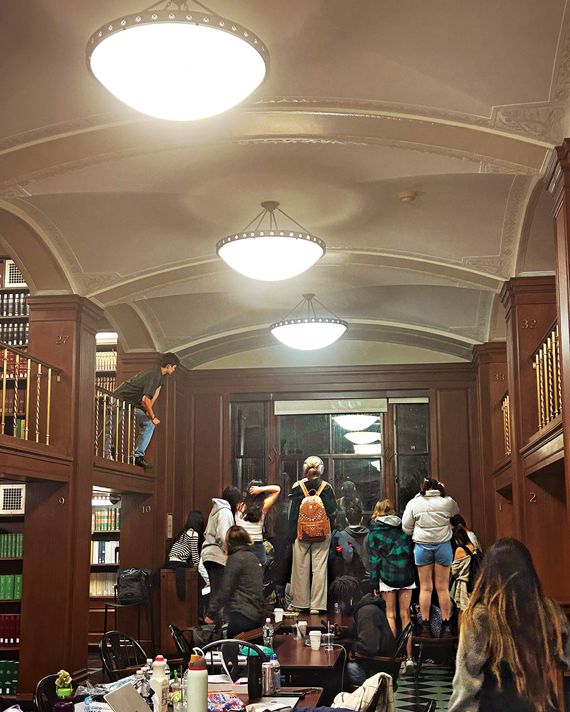

After breaching the building, the protesters sprinted up the stairs, lugging wooden tables and chairs from classrooms to block the doors from the inside. They taped black trash bags over security cameras, shuttered the blinds, plastered windows with newspapers, and chained the doors shut through shattered panes of glass. From a balcony, protesters hung a banner renaming the building “Hind’s Hall,” after Hind Rajab, a 6-year-old Palestinian girl whose death became a symbol of Israel’s destruction of Gaza. Outside Hamilton, other protesters formed a human chain while erupting in chants and songs.

Carla Mende, a graduate student: I was out there filming it with a documentary team. We had a hunch something was going to happen. We were positioned all over campus like, Oh my God, they’re moving here. They’re moving there. What are they doing? And at some point, the picket started, and then they started going to Hamilton. It was all very quick. They immediately started picketing in front of the building, linking arms, putting out trash cans and picnic tables, all of that. The banners went up. And then a building was occupied on our campus. It didn’t feel like real life.

Alex Kent, a freelance photographer: As soon as they reached the doors of Hamilton, they just went straight in. There was a lone security guard who’s by the door who was really taken aback. People behind me came out with barricades. It was 15 or 20 minutes before both the doors were shut down. It was very intentional and purposeful, and even what was damaged, like the windows, was all out of functionality. The protesters just wanted the Facilities workers out. It almost was like they were pleading with them, like, “Please, we need you to leave. You don’t get paid enough to deal with this.”

Administrators put the campus on lockdown. By 8:30 p.m., hundreds of officers in riot gear, some wielding batons and tactical equipment, marched down West 114th Street and encircled the campus. Columbia issued an emergency message to students to “shelter in place.”

S.M., a junior: I could sense the atmosphere of fear and anticipation from looking at everyone. Protesters were whispering to each other like, “Are they actually going to come?” It was all these people willing to sacrifice themselves and use their physical bodies as barriers. And that’s exactly what they ended up doing.

Kent: Around eight o’clock is when the police started surrounding. They started prepping the outside perimeter. And it was that eerie silence before the storm where everyone’s waiting for the police to enter.

At Shafik’s request, hundreds of police stormed campus. One group of officers surrounded and entered the second encampment, searching tents for protesters. Another line of officers used a mechanized ladder to enter Hamilton Hall via a second-floor window facing Amsterdam Avenue, while others flooded toward the building’s main entrance. Protesters linked arms in front of Hamilton as police approached with raised riot shields. As the human barricade gave way to arrests, protesters reported numerous incidents of police brutality. In six minutes, cops used power tools to breach a barrier made of bike locks and metal picnic tables before entering with guns drawn. One shot into an office, apparently by accident.

Cameron, a sophomore: The police came in droves. Students ran and fled from them, screaming. The police forced everyone — all bystanders, including myself, other students, press, media, medics, and legal observers — into nearby buildings. We saw the police push one individual down the stairs. We saw them violently arrest students. I was barricaded inside John Jay Hall.

Carla: I was just watching streams and streams and streams of cops come in. I would say that it was about 500 cops; it was insane. They were flooding in with body shields and heavy machinery, like giant hammers — other stuff that I don’t really know what it even was. It looked scary, honestly.

Gillian Goodman, a graduate student: It’s clear that their directive was to clear out the area of onlookers, including people clearly marked as medics and basically all press, within the span of about 15 minutes. When we really realized we were going to be barred from campus, people started trying to stand their ground more. At that point, the police behind me pressed their baton into my back and pushed me out with it.

Sueda: We were engaged in verbal combat with the NYPD. I was telling them, “This is our campus, and you’re not keeping us safe; you’re endangering us.” And one officer had the nerve to say, “We’re here to keep you safe.” Moments later, they threw our friends down the stairs. I have images of our friends bleeding. I’ve talked to friends who couldn’t breathe, who were body slammed, people who were unconscious. That’s keeping us safe?

S.M.: We were all pushed into John Jay and then they ended up barricading the doors with their batons. There were a lot of students asking the officers, “Oh, could I please go home? How long are you going to keep us here?” And through the locked doors, they’re like, “Oh, you guys are gonna stay here a while.” The bathroom was shut down for maintenance, so we didn’t have a bathroom for three hours.

Gillian: There could have been a much higher level of violence. I think we’re lucky that nobody was hurt in a way that they can’t come back from.

Kent: They were pushing protesters up against the gate and arresting them. They moved everybody all the way back to the Sundial, and I was able to photograph the NYPD sweeping the tent area; they used flashlights to make sure there was nobody still hiding. At this point, they moved most of the media so far back that the only way to see what was happening was through a very long lens. And I saw them pull out protesters from Hamilton Hall.

Gillian: The protesters were entirely peaceful; they didn’t move, they didn’t initiate any kind of violence or intimidation with the police. They didn’t pick up a stone and throw it. They literally did not move, and they sang until the police came.

Tooze: It was a moment of horror when I went up to the barriers — the physical force of the NYPD, the menace and the threat that was there. It was a horrible ending, which had, I think, a certain necessity to it. It’s hard to see how this was going to go another way, as much as I regret it and as much as I would have hoped and dreamed that the administration would see reason and move to a more imaginative, different position.

Webre: People were not shaken by the takeover of Hamilton Hall. They were shaken by the police presence on campus. It was a huge overreaction. And honestly, the first time was bad enough, but the police in the first instance were quite professional and the whole thing was handled as well as it could have been. The action at Hamilton Hall was so over-the-top. Shafik has continually chosen escalation, and that’s a huge failure of leadership.

Jillian: The violence student protesters experienced at the hands of the police is connected to the violence Israel is carrying out. We know that police are sent from the United States to be trained in Israel by IDF soldiers, and we know that they share military tactics and weapons and technologies. This is not to say that what protesters experienced here is at all comparable to what people in Gaza are experiencing right now. But we understood that it was all connected.

In the aftermath of the sweep, under Shafik’s direction, the campus remained sealed off to most students and faculty and heavily fortified by police. A day after the mayhem, as a strange quietness and emptiness filled the university, Shafik was seen emerging from the broken doors of Hamilton, escorted by guards.

J.,* an administrator: This whole experience, the last six, seven months, it’s going to stay with me for the rest of my career, if not the rest of my life. Frankly, it’s going to be one of those moments where people ask, whether it’s five or ten or however many years from now, “Where were you when …?” And we’re all going to have to have an answer.

* Some respondents asked to be identified by their first initial to protect their identity. Others are using pseudonyms, which have been marked with an asterisk.

Photographs by Gabriella Gregor Splaver, Stella Ragas, Asha Ahn, Heather Chen, Gaby Diaz, Judy Goldstein, Sydney Lee, Grace Li, Yvin Shin, and Heidi Small.