This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

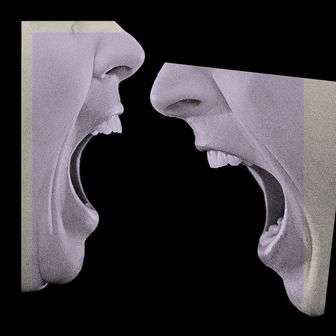

At workplaces and in restaurants, on university campuses and in playgrounds, over Instagram and along lampposts, the war in Gaza has shifted something in the psyche of New York. Family members are confronting the vast distance between one another’s sense of justice. Friend-group chats that were once warm and boisterous are turning bitter and quiet. Some of our largest cultural institutions have been riven by accusations of intolerance and censorship. At the office, co-workers leave meetings frustrated and unheard, and high-profile statements of support for Palestinian rights have led to swift dismissals. Swastikas have been found graffitied on buildings. ¶ More than 11,000 Palestinians and 1,200 Israelis have been killed since October 7. This horror has been refracted, here, into vigils and protests and moving gestures of support — as well as acrimonious arguments over who is to be feared and who is in danger. There is a pervasive sense that everyone is hurting, aggrieved, and misunderstood and no longer pretending to share a common reality.

Table of Contents

• 92NY Digs In

• Witnessing Gaza Through My Instagram Feed

• The Posters and Me

• The Public Defender Labeled a Poster Defamer

• The Fracturing of the Intellectual Left

• How Palfest Found a Home

• In Hollywood, They’re Posting With Caution

• Artists and Collectors Turn on Each Other

• Four Jewish Creative Professionals at Odds With Their Colleagues

• Teenagers Looking for Answers

• Two Rabbis Who See Hatred in Anti-Zionism

• Intimate Betrayals: Ten Confessions of Hard Feelings

• Hearst Clamps Down

• Who Gets to Protest at Columbia?

• The Student Fight Trickles Up to Faculty

• My Jewish Mom Anxiety Just Keeps Growing

• The Political Strategist Attacked for Wearing a Keffiyeh

• Four Israeli Veterans, Watching the War from Afar

• After October 7, My Orthodox Family Became Unrecognizable

• Two Palestinian Friends, So Many Losses

Cover Story

92NY Digs In

A venerable institution splits with much of the cultural elite.

By Simon van Zuylen-Wood

Eleven days after 92NY disinvited from its stage the Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen for signing a controversial open letter critical of Israel, the Y’s CEO, Seth Pinsky, meets me for breakfast at Nice Matin, the Upper West Side brasserie on the ground floor of the Lucerne Hotel, not far from where he lives. We are joined by Rabbi David Ingber, who heads the Y’s Bronfman Center for Jewish Life, and Jonathan Rosen, co-founder of the top-shelf PR shop BerlinRosen, whose role here very much falls under the firm’s “crisis management” tab. We are still three days away from the circulation of a follow-up open letter decrying the Y’s reaction to the original open letter, which would be signed by prominent authors Tony Kushner, Leslie Jamison, and John Banville, but the Y is already in chaos following staff resignations and the dissolution of its vaunted literary program.

Pinsky, 52, who made his reputation as an ultracapable technocrat in the Bloomberg administration, has a mild, thoughtful demeanor. But the Y under his watch has been getting pilloried, and he seems eager to publicly reply to the critics for the first time. “I just want to start by saying that this has been excruciating,” he says. “This is much harder than anything I’ve faced ever before. I was in government right after September 11. But there were very few people in New York who were pro–Al Qaeda. We were all in together in terms of rebuilding. During COVID, there were very few people who were pro-pandemic. We were all in that together.”

Leaving unsaid who in the current moment represents Al Qaeda or the pandemic, Pinsky’s point is that, regarding the Israel-Hamas war, New Yorkers are conspicuously at one another’s throats. If a thousand Ukrainian flags bloomed across the city in response to the Russian invasion in 2022, this conflict has been characterized by dueling protests and posters and people tearing them down. The ideological combat broke out in especially acute fashion at 92NY, a secular temple of arts and letters that also happens to be an explicitly Zionist community organization with deep ties to Israel — a microcosm of a city that in important respects remains politically and culturally Jewish. “For most of our history, the 92nd Street Y has been able to be a liberal institution and a Jewish institution,” Pinsky says. “Those core values were not in tension.” Now, it seems, they are.

Ingber’s and Rosen’s very presence at this breakfast — strategic or not — underscores the point. Ingber is the founding rabbi of the inclusive synagogue Romemu; he keeps the Israeli and U.S. flags up in his temple in a practice he calls “raising our flawed flags.” Rosen was an architect of Bill de Blasio’s 2013 mayoral campaign and belongs to Congregation Beth Elohim, the progressive Park Slope synagogue led by Rabbi Rachel Timoner, who last month wrote a New York Times op-ed about the abandonment Jews felt watching the justifications and outright celebrations by some on the left of the Hamas attack on October 7. Like Timoner and many of the Y’s patrons, Rosen and Ingber are liberal Zionists critical of Benjamin Netanyahu and now find themselves alienated from their erstwhile allies. “The same people who are feeling so hurt by this moment and so scared,” says Rosen, “have also spent, like, the last year marching in front of the Israeli Embassy protesting judicial reform and calling Bibi a fascist.”

Lest anyone think Pinsky is going to apologize or placate, he’s actually here to aggressively defend the Y’s position. Which suggests the schism over the Gaza conflict, especially within elite institutions in New York already riven by competing ideological factions and financial pressures, will not be a passing disturbance but an enduring fault line.

Witnessing Gaza Through My Instagram Feed

By Zaina Arafat

Bisan Owda, or wizard_bisan1, as her 2 million followers know her, was a filmmaker before the assault on Gaza began. In a video from October 12, she offers footage of her prewar office. It looks like a typical millennial media workspace: camcorders, whiteboards, couches, a fluffy cat napping across a desk. She has discovered the office was bombed. “I know it’s not a suitable time to talk about places and homes because people are losing their lives,” she says in the video, her eyes welling. ‘‘People are being killed.” Even within Gaza, there’s a hierarchy of suffering.

Owda, 25, describes herself as a hakawatieh in her bio. A storyteller. Now, she is suddenly a journalist. In Gaza, the line between civilian and journalist seems irrelevant as neither is safe. In each of her videos, her long dark hair is pulled back, a mess of curls atop her head or behind her in a pouf of a ponytail. She wears braces, an assortment of loose-fitting T-shirts, and denim button-downs. Her live reports vary in tone. In a recent video, she calmly explains what Gaza even is, geographically speaking. That same day, she fights back tears as she describes the lack of food and water. “We are dying because of hunger,” she says, shivering. Some of her videos are in Arabic, but most are in English. That way, from Gaza she can reach the previously unreachable — that is, the West. Every morning, I check my feed in the hopes of finding something from Bisan. My stomach tightens with each scroll until she appears. “I’m still alive,” she usually begins.

Alongside Owda on Instagram are 22-year-old Plestia Alaqad and 24-year-old Motaz Azaiza, both journalists livestreaming the war. In a video from October 9, Alaqad shows us the view from her neighbor’s balcony. “There is no view,” she says, panning across hazy silhouettes of buildings through the dust. Her shoulder-length hair often blows in the wind created by explosions that you can hear in the background. In Azaiza’s videos, he acknowledges the shame of filming his fellow Gazans during their most devastating moments. In a particularly haunting video, a little boy sits shaking in what appears to be a hospital, though no doctors are present. The camera pans to a boy next to him with a bandaged head and burn marks up and down his arms. The scene plays over and over in my mind.

The Posters and Me

By Mark Harris

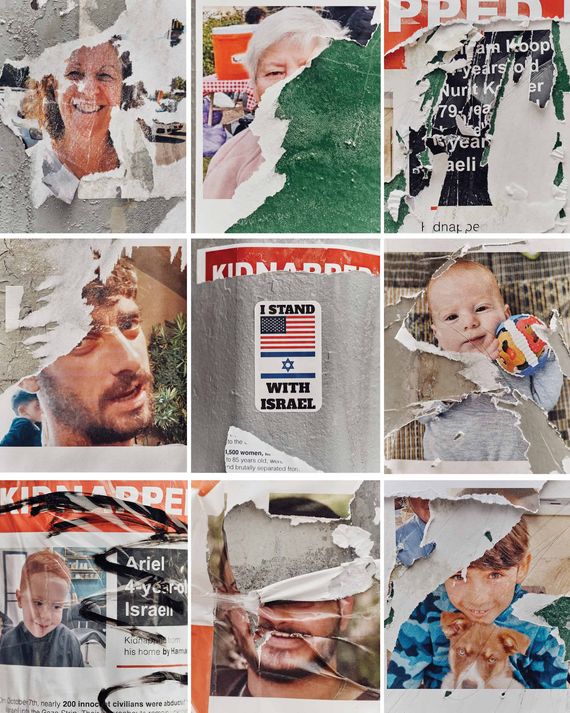

I saw someone ripping down one of those KIDNAPPED posters the other day. I live in a neighborhood where there are a lot of those posters. I have no idea whether the person ripping them down is Jewish, Muslim, Israeli, Palestinian, or none of the above. Honestly, their vibe was none of the above; their vibe was “college.” Their expression was blank and even and stony, the face people put on when someone asks them for money on the street and they are not going to make eye contact or break stride but they still want to manifest the plausible deniability of cruel intention that adds up to a performance of civility. This person was on a mission; part of the mission was that they were not going to engage about the mission. I wondered what the mission was. I don’t know. I flinched when I saw the tearing-down. It felt aggressive, though I am as sure as I am sure of anything that this person did not think of themselves as aggressive and would have taken offense at the word. The next day, the posters were back up, now entirely covered in clear tape; if someone wanted to get rid of them, they would have to use a box cutter.

Soon after that, they were box-cuttered down.

Soon after that, they were up again in new places.

This angry, silent, futile proxy war being fought by mostly anonymous combatants, lamppost by lamppost, feels like a perfect realization of the mistrust and noncommunication that has seized much of this city since October 7 — a city shared by huge numbers of Muslims and Jews, though the visibility of the two groups is certainly not equal.

The Public Defender Labeled a Poster Defamer

By Esther Wang

On the evening of November 2, a few dozen people gathered around the traffic circle at the southwest end of Prospect Park for a candlelight vigil. They were there to honor the thousands of Palestinians who had been killed by Israeli air strikes since the start of the war between Israel and Hamas.

Victoria Ruiz, a public defender with New York County Defender Services, was standing with two of her colleagues, listening to one of the vigil organizers reading off a list of the dead, when a handful of people arrived. “What about Hamas?” some yelled. According to one of the organizers, one man walked up to the altar he had made for Hala Abu Sa’da, a 13-year-old killed in Gaza, spit at it, and challenged those present to fight him. The counterprotesters began taping up posters featuring the photos of Israeli hostages of Hamas. Ruiz had seen similar posters all around the city, the ones that read KIDNAPPED with a call to bring the hostages home. The posters had never really bothered her — she wanted the hostages to be released too, just like she wanted the bombing to stop. But as she looked more closely at these posters, she read a more provocative message typed and handwritten onto them justifying the murder of Palestinians. She was suddenly overcome with emotion. How dare people come to a vigil for the dead with this, she thought.

Ruiz began ripping down one of the posters — and in the midst of doing so, she realized she was being filmed by one of the counterprotesters. As they filmed, they called out, “Why are you taking down pictures of missing children?” Immediately, Ruiz felt alarmed. Did she just get baited?

A few nights later, Ruiz and her partner were relaxing at the home of a friend after attending another pro-Palestine rally, this time in Washington, D.C., when she began receiving a flurry of phone calls from strangers and comments on her Instagram posts calling her a “Hamas terrorist” and telling her to “go back to Gaza.” She quickly discovered why: Minutes earlier, the group StopAntisemitism had posted a 17-second video clip3 of her tearing down the posters at the vigil and identifying her by name. “It is absolutely unacceptable for someone with such bias and hate to serve in your office,” the post read, tagging the account of NYCDS.

When Ruiz saw the video, her stomach dropped. “I was just, like, Damn it, now I’m in this weird crossfire,” she recalled. “It made me really scared because I was like, If they were able to pick me out of that vigil, then whoever is doing this must have all my information.” She also began worrying what it would mean for her job.

The Fracturing of the Intellectual Left

By Ryu Spaeth

Joshua Leifer, a graduate student at Yale, is a soft-spoken leftist whose thoughts unspool in long, eloquent paragraphs. In this respect, he is like his peers in the small bowl of soup that is the world of leftist magazines, a group of writers and editors who know one another, sit together on editorial boards, and attend the same issue-launch parties. But it is their differences that have been most pronounced ever since Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel, their gentle voices belying the vehemence of their disagreements. “A segment of the left’s moral compass seems to have broken,” Leifer told me over the phone from New Haven.

The argument playing out in a handful of New York–based journals — most notably n+1, Dissent, and Jewish Currents — may seem like the intramural squabbling of underpaid scribblers on the margins. As Mark Krotov, the co-editor and publisher of n+1, told me as we entered the magazine’s airy office loft in Greenpoint, “We like to joke that we are never more relevant than when the world is being convulsed by historic events.” But in truth, this debate has shaped the rhetoric and agenda of the broader left, which in the past ten years has become an influential bulwark composed of an array of groups and figures including self-described communists, the Democratic Socialists of America, and popular Democratic Party officials like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. This debate has also revealed fissures that remain raw and open and, some fear, may be long-lasting. “I believe the Jewish left will never be the same,” said Celeste Marcus, managing editor of the journal Liberties.

The initial point of contention was how to respond to the events of October 7, which the New York Times, among others, described as the single worst attack on the Jewish people since the Holocaust. In a widely read essay in Dissent, Leifer denounced members of the left who celebrated the attack or refused to sanction it, including an n+1 contributor who had scorned the “smarmy moralizing about civilian deaths.” This prompted an impassioned rebuttal, also in Dissent, by Gabriel Winant, a professor at the University of Chicago, who said the focus on Jewish victimhood fed into “a machine for the conversion of grief into power” and further oppression of the Palestinians. The argument has since grown to encompass a constellation of questions surrounding the leftist project: whether it is too extreme to appeal to people to its right, whether it has exposed latent Stalinist tendencies, and whether it can even keep its own movement together.

The crisis has perhaps been most acutely felt at Jewish Currents, a magazine that brings together in its pages the aspirations of the Jewish left and the Palestinian liberation movement. Editor-in-chief Arielle Angel, who wrote a plaintive essay that strove desperately to bridge the divides between these two groups, sees this as an “existential moment” for their alliance, which has to reach people outside the coalition who may be willing political partners. “What we are watching is a full reactionary moment among many Jews, even some left-wing Jews, because they feel there was no space on the left for their grief,” she said, “which I think is a fair assessment.”

How Palfest Found a Home

Shortly before October 7, the Palestine Festival of Literature had planned a small, unpublicized private fundraiser in New York. It was slated to be held at McNally Jackson at Rockefeller Center on November 1 featuring speakers such as authors Ta-Nehisi Coates and Rashid Khalidi. About a week before the event, the festival’s organizers decided to change course. “With everything happening in Gaza, we felt this urgently needed to turn into a big public event,” said Yasmin El-Rifae, one of the main organizers. “But We Must Speak,” PalFest’s first public event in New York, quickly began to take form, involving all challenges typical of last-minute preparation. Invitations were sent to poets and speakers; publicity and advertisement was arranged. To accommodate a larger audience, the organizers would have to move the festival from McNally to a bigger location.

Before they had a chance to communicate that to the bookstore, they were told they could no longer hold their event there. Tishman Speyer, the real-estate company that owns Rockefeller Center, rescinded its approval for the use of the store’s space, against the wishes of Sarah McNally, who owns the McNally Jackson bookstores. “She was outraged,” El-Rifae said. Then the other venue rejections started coming in. “What we found was a landscape where many venues were just no-go zones to start with,” El-Rifae said. The organizers asked Riverside Church in Morningside Heights for use of its main sanctuary space. “They would not let us use it for anything remotely sensitive,” she continued. “Places of worship like churches, a lot of their board members were just turning down our ask.” Two uptown Manhattan churches, whose names El-Rifae chose not to disclose, also declined to host PalFest with neither citing specific reasons for the rejection. PalFest eventually reached out to Jewish Voice for Peace, the organization known for progressive organizing, asking for help. “They understand they can offer a layer of protection because it is harder to call them antisemitic,” El-Rifae explained. The organization’s rabbinical council wrote letters on behalf of PalFest to multiple churches, asking they open up their spaces.

Two days before the event, PalFest secured a space at James Memorial Chapel, across the street from the Riverside Church, with the help of Michelle Alexander, who is a student at Union Theological Seminary, where the chapel is housed. (Riverside gave the festival organizers access to its assembly hall in the basement of the church as an overflow room, where attendees watched a livestream.) El-Rifae says there was a “historical power” in holding the event at the chapel. It’s the location from which Martin Luther King Jr. had originally planned to give his speech about breaking the silence around Vietnam in 1967. In the end, the crowd was so large King moved across the street to Riverside Church, where he delivered his speech from the sanctuary room. “So there’s a sort of sad irony that we were denied use of it.” El-Rifae added.

— Najwa Jamal

In Hollywood, They’re Posting With Caution

As told to Rebecca Alter

A Middle Eastern Actor

I have played Palestinians, Israelis, Iraqis, Afghans — every version of that you can imagine. I once played a Palestinian character, and someone asked me if I “related to my character,” who was a freedom fighter. My job is to relate to the character I’m playing, so I replied, “I don’t believe in violence. I’m a pacifist. But I do relate to my character because he has gone through trauma and he’s trying his best outside of the violence. I can understand and empathize with his POV.” And the conversation erupted into me being called a Nazi. I get emotional about it because I grew up in a house of immigrants that cared for everyone in our town, especially our Jewish neighbors. I was like, Oh, fuck! People are thinking this is antisemitism and not anticolonialism.

I do feel there’s pressure on me as a MENA actor in Hollywood. I’m selective about how I post online. When the attack happened, I immediately put out posts with regard to how fucking disgusting Hamas is, because it is. And immediately, the Middle Eastern community, which is not a monolith, jumped on me. Like, “What about Palestinians? I see your true colors.” When I post things that focus on innocent children and good people in Gaza who are just trying to survive, people comment, “What about the Israelis who were kidnapped?”

What happened to Maha Dakhil, the CAA agent who lost her leadership role for calling the war a “genocide,” scared the shit out of us. I’m very careful not to use words like genocide, occupation, colonialism, open-air prisons — despite believing they do accurately describe what’s happening in Gaza. Those put a target on your back. I also don’t use the word unprovoked. A lot of people say October 7 was “unprovoked.” Well, it’s a massive chicken-and-egg situation, this back-and-forth. Also, I didn’t know the word cease-fire would be such a problem! I would hope we don’t want wars!

A Jewish Showrunner

I find it hard to articulate a singular conversation in Hollywood right now. But in the immediate wake of the initial attacks, all people who identified as Jewish came together and were like, “How are you doing?” “How are you feeling?” And “I’m scared.”

The picket lines would have been a natural place to process all of this. But the writers’ strike ended right before the attacks happened. Online discourse happened so quickly. The equivocating was instantaneous. Everyone was trying to find comparisons. What if First Nations people came into your backyard and started massacring you because you’re living on stolen land? These are not accurate comparisons. When we talk about war, and the things you are allowed to do and not allowed to do, I thought we had agreed ethically and morally that you’re not allowed to kidnap someone. And it turns out no such agreement was in place.

I used to post on Instagram a lot. It’s the only social media I use. And then I was like, I have an Instagram problem. I’m looking at this too much, and nobody cares what I think. So my posting became sporadic. After the attack, I was seeing what was happening on Instagram and to the Amy Schumers of the world. And then there’s all of these incredible activists I follow, particularly inside First Nations communities, the Latin community, mostly the Black community. Although some of the things they’re saying are upsetting to me, they’re also landing and making me think. They made me go, Do I have this fucking wrong? Or is this antisemitic? I was in a broad state of confusion.

Artists and Collectors Turn on Each Other

The Artforum letter was just the start.

By Rachel Corbett

On October 19, Artforum’s website published “An Open Letter From the Art Community to Cultural Organizations,” calling for Palestinian liberation and “an end to the killing and harming of all civilians, an immediate ceasefire, the passage of humanitarian aid into Gaza.” The letter did not originate with Artforum’s editors. It had been circulating as a Google form, where it had already been signed by more than 4,000 people, including Judith Butler and Fred Moten and, as David Velasco, the magazine’s editor of almost six years, put it, more artists who had made the cover of Artforum “than I’d ever seen in one space”: Barbara Kruger, Kara Walker, Nicole Eisenman, Nan Goldin. “This was the first moment where it felt like there was consensus, where you had thousands of people signing something saying, ‘We can agree on this’ — people who would normally find it impossible to agree on anything. So I thought, This is the beginning of a coalition,” he said. While the letter made a point to “reject violence against all civilians, regardless of their identity,” it did not mention Hamas or the murder of more than 1,200 Israelis on October 7. Velasco signed it himself.

By the next morning, the publishers were getting calls. Marianne Boesky, whose gallery’s ad happened to appear amid the petition on the website, reached out immediately, saying, “I need you to remove my name and my gallery’s brand from supporting this statement.” Gallerist Dominique Lévy also called to complain about the petition, which she described as “one-sided and biased and disrespectful to the core.” It flouted “the rules,” as Boesky put it, “that you must condemn Hamas before you can support any Palestinian base from being killed.” Many collectors and other dealers were also upset, and a week after publishing the letter, Velasco was fired.

There’s “a long-standing tension,” artist Hannah Black said, whereby “artists are far more likely to be aligned with revolutionary positions than collectors and trustees.” In the past decade, arts workers have increasingly made activist demands, ousting board members, organizing labor unions, “occupying” and “decolonizing” museums. The art ownership and leadership class — which tends to be older and whiter and wealthy — has grown increasingly irritated, if mostly behind closed doors. Nobody wanted to say the wrong thing, so they mostly listened, or pretended to, and didn’t engage. “Political correctness is like a religion here,” the dealer Amalia Dayan recently told Haaretz. “You have to be cautious all of the time.” Now, these resentments have spilled out into the open.

“This Palestine-Israel thing strips the Band-Aid off that toxicity. This is actually how fucking ugly it really is” in the art world, said the collector Stefan Simchowitz. And he sees that it’s becoming personal for many: “They’re now wondering, ‘Do I like the curators at the institutions? Do I like the educators? Do I in fact even like the fucking artists I’ve dedicated my life to supporting?’ It creates a real existential crisis for the art world.”

On both sides are those who would prefer the other be seen and not heard. Plenty of artists would love collectors to stay in their lane, giving money and not advice, and many collectors would rather artists “stick to art.”

Four Jewish Creative Professionals at Odds With Their Colleagues

Ella, 30, is an Israeli artist who has lived in Manhattan for ten years; Adam, 28, is a curator and graduate student in Manhattan; Sam, 34, is an art director in Brooklyn; and Natalie, 25, is a clothing designer in Queens who was born in Israel and has close family still living there.

Ella: With this war and violent attack, people right away started justifying why we were being killed. And then a little bit after that, they stopped justifying it — they started denying that it even happened. Right now, in the creative industries — the world of design and art and cinema — that’s the general opinion. Those are the prominent voices.

Natalie: I don’t know how I’m supposed to feel when I’m mindlessly scrolling through Instagram, and I have to see my boss like a post that shows car graffiti that says “Fuck Israel.” Am I supposed to work under these people that are posting this stuff? And then I have to walk to work looking at these torn-down posters. It’s very isolating.

Sam: I work for a high-profile company, and a lot of my co-workers are just idiots. I really love them. Or loved them. But I try to not engage. I would love to scream at the top of my lungs, but for what? It’s too deep in our industry.

Natalie: I’m the only one from that region in the office. I have co-workers who are like, “You need to take care of yourself. You need to not think about it. You need to not talk about it online or fight with people online.” But when I go home, I just spiral. I’m not going to stay silent.

Adam: I had this conversation with my dad last week, where I was like, “Oh, this is why Jewish parents want everyone to be a doctor or a lawyer.” It’s tough to be a part of the entertainment business right now. Any person who’s creative feels this sort of obvious push. It’s hard to just push Jews out. It’s better to just push Zionists out, you know what I mean? There’s a conditional love for Jews only if they’re anti-Zionist. It’s very ingrained, this feeling, like I’ve got to hop on that train or I’m gonna miss out on work opportunities.

Ella: I do feel that I’m losing opportunities. I see how many emails and requests I get. This is a time of the year that I’m usually working a lot. I’m holding maybe two jobs, but usually before the holidays, there’s a lot more—it’s one of the busiest times of the year. And also, in terms of galleries and interest in my art being displayed.

Adam: There’s a lot of rhetoric about BDS, this whole divest and boycott thing toward any Zionist institution. It’s quickly seeping into not wanting to hire or work with people who are deemed Zionist, and if you are Israeli, it’s very easy to —

Ella: No, but it doesn’t matter what your opinions are. I have friends who are peace activists and work in peace building, but they’re Israeli, so their business is being threatened right now. In New York. At this point, I think I’m going to have to find a new profession. I think we’re going to be deplatformed and alienated. Sometimes I think I’m spoiled to think What galleries can I be in? Someday I can go back to school. I can have another job to protect myself. I don’t know if I’ll continue living in New York.

— As told to Julia Edelstein

Teenagers Looking for Answers: Scenes From Four New York High Schools

By Anya Kamenetz

A Flag-Football Team Caught in a Protest

MESA Charter High School’s flag-football team was getting nervous. In the weeks after Hamas’ attack on Israel, team members at the school in Bushwick were warned not to go to Hasidic Williamsburg. “We didn’t know what the response was going to be in that neighborhood,” says Aisaac, a 16-year-old junior with an air of unflagging sincerity. “I was warned to steer clear out of my own safety.” Then, on October 28, the team had another game, this one in Downtown Brooklyn. A large pro-Palestinian-rights march passed their playing field on the way to cross the Brooklyn Bridge.

“The whole street was filled,” explains Aisaac’s teammate Genaury, a senior with curly hair and glasses. The team stayed put, watching, until well after dark. “My coach was asking me, ‘Where are you going?’ He didn’t want me walking out into that crowd. God forbid something happens. At the end of the protest, a bunch of cop cars and vans were following. I felt shocked. It was completely random to me.”

MESA shares a low-slung concrete building with two other small schools in Bushwick. It’s tight-knit and working class; 97 percent of students are people of color, and they often have to work and take care of younger siblings along with all the regular high-school stuff. “I’ve got football, National Honor Society, community service,” says Aisaac. “By the time I get home, I’m just ready to collapse, but I still have to do work.” What they do understand of the conflict is filtered through their phones. Jordi, a senior with lime-green hair who’s the team’s wide receiver, recalls seeing “a post that showed the stats of little kids and babies dying. It’s so sad and devastating. They didn’t cause anything, little babies and kids.”

There hadn’t been much discussion about the war in classrooms or among friends or even at home. Aisaac raised it to his teacher in the current-events section of his U.S.-history class: “I brought in an article and I asked for a little more context behind it. She spoke about how she thought it was a negative thing that was happening. She thought it was terrible to see all these deaths.” He was left with a lot of unanswered questions. “It made me want to understand it even more. I’m getting bits and pieces. I’m just somebody watching this happen.”

Two Rabbis Who See Hatred in Anti-Zionism

Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch, the senior rabbi at the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue, a Reform congregation on the Upper West Side: It goes without saying it’s not antisemitic to criticize the Israeli government. What is problematic is to deny the right of Israel to exist. And all associated, adjacent, and related slogans to that effect are, in almost every case, antisemitic in either intention or in nature. “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” Everybody knows what that means. That’s not aspirational. Just go and ask the people who are chanting what that means — it means the destruction of the Jewish state because Israel was a colonizer and doesn’t have a right to exist. That is, in almost every case, antisemitic. This stance is antisemitic on two levels. One, because Israel is central to Jewish identity worldwide. And secondly, what would you do with those people, the 7 million Jews in Israel? Where would they go? We know what would happen to them if Israel’s enemies had the power to deal with them as they wanted. That’s what happened on October 7.

Rabbi Rachel Ain, the senior rabbi of Sutton Place Synagogue, a Conservative synagogue in midtown: For those who say, “Well, there are Jews who are anti-Zionist”: I think that in Jewish life, there are boundaries. And Zionism, for me, feels like a boundary. In mainstream Jewish denominations and federations, Zionism and Judaism go hand in hand. And while there might be people who struggle with how Zionism should be enacted, Zionism is a core value that makes up the totality of what it means to be Jewish.

Rabbi Hirsch: I agree with you, and I would add that if you do some research into the composition of an organization like Jewish Voice for Peace, you’ll see that they’re not all Jewish and they’re certainly not a voice for peace. And that’s because there is no peace in an anti-Zionist solution, which means the dismantling of the Jewish state. And, of course, that’s not going to happen, so there’s no basis for discussion with them.

Rabbi Ain: My synagogue is a community that cares about American values beyond the Jewish community. And we don’t see our Zionism as a rejection of those other values. What’s so deeply disappointing is the line that seems to have been drawn when it comes to Israel and the Jewish people. We are the ones who have gone to the West Bank and to Ramallah and who have spoken about the importance of Palestinians having sovereignty and the need for security and self-determination. And I still believe in that, but it can’t be at the expense of the Jewish state and Jewish lives either.

Rabbi Hirsch: Zionism is a liberation movement. It was established by liberals and is committed to liberal principles. That doesn’t mean we don’t have disturbing trends within the Zionist movement. But the idea that an ancient, persecuted people have a legitimate right to self-determination, like all the other peoples of the world have, is a liberal idea. What we are seeing now in some quarters of the liberal world — again, not in the corners that are criticizing this or that Israeli policy but among those who proclaim in the name of liberalism that Israel has no right to exist, it’s colonial, it’s repressive, it’s apartheid, it’s racist — those corners represent a fundamentally illiberal worldview. They’re not representing liberalism.

— As told to Julia Edelstein

Intimate Betrayals: Ten Confessions of Hard Feelings

As told to Bindu Bansinath and Anya Kamenetz

Worried for Her Daughter

I’m a Jew living in New York with a daughter at a liberal-arts college outside the city. She has a friend in school she’s known for three years. Before the conflict, he and I had a great relationship. He used to visit our home.

My daughter and I don’t think what the Netanyahu government is doing is okay, but after the October 7 attacks, I was shocked by what her friend was posting on social media, insinuating that what happened was Israeli propaganda. The general sentiment of it was Israel deserved it.

After seeing the posts, I called him. We had a conversation, during which he showed little compassion for the victims. He told me there were no babies beheaded; he’d seen a video of a Hamas attacker being interviewed and told me, “I see a brown person being interrogated and oppressed.” I explained to him there are brown Jews. It’s hard when people find it impossible to even say, “It’s horrible what happened,” or they’re saying it didn’t happen. I brought up to him that Hamas had raped women. He said, “Maybe there was rape.” I was dumbfounded. These are liberal-arts students who are supposed to be supporting women’s rights and minority rights.

When I brought up my offense at what he said, he basically made me feel like an old lady who doesn’t know what the hell I’m talking about, that I don’t understand propaganda, that I don’t understand how I’m being brainwashed. We ended the phone call on a cordial note but had a last text exchange that was quite terse, where he again stated no babies were beheaded. Nothing will ever be the same again.

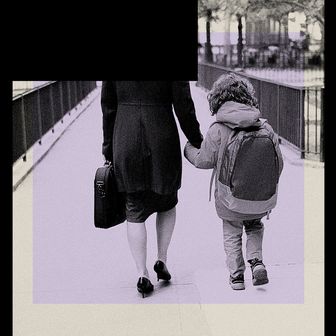

I’d reached out to him because I was scared for my daughter. These are kids she goes to school with. She tries to tell me everything’s fine, but she’s been coming home on the weekends. I don’t know how she found out about our phone call, but she was mortified when she did. She said I’d crossed a boundary and that I could not discuss this with her friend. I told her I was sorry.

Armed With Hair Spray

I am a Palestinian with family in the West Bank. They’re scared. They don’t leave the house. I’ve lived in the U.S. for 37 years. I’m one of very few Palestinians and women who wear a hijab in my place of work. People whom I work with on a daily basis now barely look at me. It has felt like I cannot speak, and if I do, I have to be very careful what I say and whom I say it to. The leadership at my work has publicly villainized the protesters. They’ve said anyone who goes to a protest is celebrating the deaths of Israelis.

There are some colleagues whom I worry about if I have to go to a meeting or be on any calls with them and they try to corner me and say, “Hey, do you support what happened on October 7? Do you support Hamas?” I remember what it was like after 9/11, when I was constantly having to prove myself. I had to be more American than anyone else. Even something as simple as posting “Free Gaza” is seen as hate. You have to stand with Israel or you’re a terrorist. Either we have to bite our tongues and not mourn the people who are dying in our families, or we have to criticize our own people for being killed in order for Americans and New Yorkers not to attack us. People are so scared to mourn. I will not put on headphones when I’m going home. I have to be super-vigilant. I started carrying a mini hair spray in my purse because pepper spray is illegal in New York. Hair spray allows us to get away from a situation that can potentially put us in danger.

Hearst Clamps Down

On November 6, employees of Hearst Magazines opened a companywide email to find an unwelcome surprise: a sweeping new social-media policy that would apply to all staffmembers’ personal and professional accounts. “If a post wouldn’t make it into our publications — whether because of language, tone, accuracy, its position on a public or political issue, or its likelihood to inflame or engender controversy — it should not be posted on social media, whether on a Hearst account or a personal one,” the policy warns. What type of content that could refer to seemed confusing to employees — especially so at Hearst Magazines, which often publishes voice-y pieces on subjects like “sideways oral” and King Charles’s nieces and nephews alongside political content that might “engender controversy.” The policy adds that managers could tell employees to delete content they find “objectionable” and that even liking posts by others could be a violation. As if that weren’t enough, it urges people to report on each other for perceived infractions. Hearst sent the policy via DocuSign and asked employees to sign it.

“We did not know it was coming,” one editorial employee said. When she read it, her jaw “went to the floor.” It “felt far-reaching and simultaneously extremely patronizing” and not “grounded in how real people use the internet.” Without knowing Hearst’s position on every issue, how could anyone even know how to adhere to the policy?

Many think they know why Hearst introduced the policy right now. On October 10, Harper’s Bazaar editor-in-chief Samira Nasr posted an Instagram Story calling Israel’s decision to cut water and power to Gaza “the most inhuman thing I’ve seen in my life.” The New York Post wrote it up the following day, quoting an anonymous Hearst employee who said, “Really? That’s the most inhumane she’s seen? So, murder, rape and beheading is not?” Nasr later publicly apologized, but her comments seemed to touch a nerve at Hearst. A day after her initial comments, corporate leaders disclosed holdings in Israel and announced that Hearst would donate $100,000 each to three organizations, including the American Friends of Magen David Adom and the UJA Federation’s Israel Emergency Fund.

The policy doesn’t mention Nasr by name, and Hearst Magazines has not given an explanation for it. “I think it’s pretty clear it’s an attempt to stifle any sort of political commentary, specifically about the war in Gaza right now,” said a union member, who, like most, spoke anonymously, fearing for their jobs. The timing troubles some employees, as does Hearst’s treatment of the top editor. When Hearst Magazines announced that Nasr would take the helm at Harper’s Bazaar three years ago, her hiring looked like the start of an inclusive new era. Nasr, who had been the executive fashion editor at Vanity Fair before coming to Harper’s Bazaar, is the first woman of color to lead the magazine. When she announced her new role on Instagram, she introduced herself as “the proud daughter of a Lebanese father and Trinidadian mother” with an “expansive” worldview. Hearst itself celebrated Nasr’s “important voice” in a press release. “It’s not lost on a lot of us that this is happening to Harper’s Bazaar’s first editor-in-chief of color, who has previously spoken openly about having Muslim family members,” one Harper’s Bazaar employee said.

No one I spoke to intends to sign the policy. Employees said that Hearst hasn’t pressured them into signing either — at least not yet. The Writers Guild of America, East, which represents editorial staff at Hearst Magazines, has filed an unfair-labor-practice suit over it, citing the company’s failure to bargain. The company may have realized it’s on shaky legal territory with the union. But disgruntlement over the policy extends beyond the union. It will, of course, affect everyone. “I have yet to hear anyone, union member, nonunion member, managers, EICs, who like this policy,” said Zach Lennon-Simon, a shop steward for the union. “It’s pretty impressive.”

— Sarah Jones

Who Gets to Protest at Columbia?

What led the university to suspend pro-Palestinian student groups.

By James D. Walsh

After standing through a three-hour protest on Columbia University’s quad, Mohsen Mahdawi and a few other students grabbed salads and soggy pizza slices from the dining hall and collapsed onto couches in a quiet, glass-walled room inside the student center. “I originally tried to reserve this room as a place for Palestinian students to mourn, but the school delayed and delayed,” said Mahdawi, co-president of the Palestinian Students Union. “Finally, they gave it to us for a few hours tonight.”

The protest on November 9 was the latest in a string of actions organized by student groups since early October, and, as far as campus protests go, it had been boilerplate. A few hundred students gathered on the Low Library steps, staged a die-in, showed off an art installation, and read demands through a bullhorn. Mahdawi watched from the periphery. At 33, he is conspicuously older than almost all of his undergrad peers. He was born in the West Bank and spent most of his childhood in the Far’a refugee camp, where, at age 10, he says he saw an Israeli soldier shoot and kill his best friend. A few years later, a soldier shot Mahdawi through the leg, leaving a scar.

Halfway through the rally, a passerby unaffiliated with any Palestinian organization made a scene, shouting an antisemitic, racist rant. Mahdawi confronted the man even before campus security arrived, then took the bullhorn to condemn him. “Shame on him! Shame on him!” Still, hours later as he sat in the student center, the interaction vexed Mahdawi. He worried the outburst would reinforce the perception that protesting Israel’s military campaign was antisemitic. “I wanted to say, ‘This guy does not belong to us. This guy is confused. We condemn this,’” he said, his voice tired and raspy, “‘and we reassure you that we are against anybody who is antisemitic.’”

Mahdawi’s condemnation did little to mollify campus administrators. The next day, Gerald Rosberg, a senior vice-president at the university, suspended Students for Justice in Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace, the organizations that staged the protest, for the remainder of the semester. Columbia isn’t alone — Brandeis no longer recognizes SJP, and George Washington has suspended it. Ron DeSantis has ordered all of Florida’s public universities to disband their chapters, though that effort may be hindered by a First Amendment lawsuit.

In a statement, Rosberg said the protest had been an “unauthorized event” that had “included threatening rhetoric and intimidation.” Mahdawi texted me an hour later: “Brother, campus is on fire.”

The Student Fight Trickles Up to Faculty

From the steps of the Low Library at Columbia, a group of faculty members and graduate students huddled together, banging pots against the wind. They were protesting the school’s suspension of Students for Justice in Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace, two groups that held pro-Palestine demonstrations that the school claims were “unauthorized” and promoted “threatening rhetoric.” The faculty passed around a megaphone. “We are here to tell the students,” said Premilla Nadasen, a small, gray-haired history professor at Barnard, “they can suspend an organization, but they cannot suspend a movement.”

In the past few years, two factions of Columbia faculty have cemented their stances on Israel and Palestine, trading open letters for and against investing in companies in Israel and the building of a research center in Tel Aviv. Within each, a core group of around a hundred remain consistent, locked in an eternal bureaucratic feedback loop. But after October 7, students’ fervor has, in some ways, trickled up. It pushed “a lot of people into a corner they had not been in before,” says Bruce Robbins, a professor of comparative literature. Faculty members who had previously felt reluctant to express personal political views on campus now see no other option. After the backlash to a Students for Justice in Palestine letter professing “full solidarity with Palestinian resistance,” more than 170 faculty members signed a letter defending the students attempts to “recontextualize” the October 7 attack. More than 400 signed another one “horrified” at the first.

Tension had already been building among some faculty members. The day after the attack, Joseph Massad, an Arab-studies professor, published an article in the Palestinian outlet Electronic Intifada calling the attacks a “stunning victory of the Palestinian resistance over the Israeli military” and, in particular, stating that the sight of Hamas breaking through Israeli borders was “awesome.” One Israeli faculty member who describes himself as a “progressive liberal leftist” and agrees with a lot of what Massad has written, took issue with the article. He had signed an open letter objecting to the suspension of SJP and JVP but wanted to talk to Massad about the half-life of his words. “The word ‘awesome’ has been said over the last month in Columbia more times than it ever was,” he says. “I wanted to not confront him about his opinion, but I wanted to show him the results of his choice to not retract his words.” He consulted senior colleagues about how to address it directly with Massad, and they advised him not to. “They’re not silencing me because it’s not my field of research or anything like that,” he says. “It doesn’t harm any academic work. But they just think it won’t help if I, as an Israeli, go to him, as a Palestinian, and talk about that.” On most topics related to the Israel-Hamas war, the Israeli faculty member feels stuck. “With a lot of Israelis, I’m considered pro-Hamas just because I support human lives in Gaza,” he says. “And within my department, I’m the Israeli. So when we debate how to phrase open letters or internal letters, if I don’t speak up, no one will speak on the Israeli side.” I ask if that’s ever uncomfortable. “Yes,” he says. “But being uncomfortable is fine.”

While some entire departments received internal emails advising them not to talk about the conflict in the classroom at all, others are historically vocal. One former professor who taught Middle Eastern studies within the History department says he felt he was perceived to be “insufficiently committed to the Palestinian cause” after repeatedly refusing to sign open letters throughout the years relating to divestment and academic programs in the region because he felt cutting off relations with scholars in Israel was a “very bad idea.” It was not a perspective many of his colleagues appreciated. “I get the sense both personally and professionally,” he says, “that a number of faculty in the Middle East field were happy to see me go.”

Mahmood Mamdani, another professor in Middle Eastern studies, says maintaining friendships with other tenured professors over the years has meant knowing when not to talk about it. His neighbor is Jewish historian Michael Stanislawski. “We would often meet and discuss, but we knew what was delicate and therefore to stay away from it,” he says. In the early aughts, after a pro-Israel group made a documentary alleging that Massad and a number of other faculty members had unfairly targeted Israeli students in the classroom, Mamdani and Stanislawski ran into one another on the subway. “I remember beginning to talk about it,” Mamdani says. “And Michael looked at me and just put up his hand like a STOP sign. I realized this was forbidden territory.”

At the protest, Mamdani spoke candidly. He believes violence is a necessary part of resistance, and he isn’t afraid to say it. The crowd grew hushed when he spoke of the value of force in fighting an oppressor. “Agree to disagree,” yelled a voice behind me as he spoke. “Respectfully,” they added, quieter this time. “Respectfully agree to disagree.”

— Paula Aceves

My Jewish Mom Anxiety Just Keeps Growing

By Bess Kalb

A group of my progressive Jewish friends and I have met every weekend since October 7 to talk and light Shabbat candles, which is something I rarely did before, unless my grandmother is reading this, in which case I do it every week. We talk about how we hold two endless griefs; it’s our attempt to feel less isolated in a duality so many Jews are feeling. We’re shattered by the 7th, and we’re horrified by Netanyahu’s response. It feels like a shiva for our own sanity.

Since the 7th, I sense a constant drumbeat of anxiety, which for a Jewish mother is nothing new. A few weeks ago the synagogue where my son goes to preschool was vandalized with graffiti. I stood with a good friend as we watched the custodians power-wash it into the gutter. “At least it wasn’t a swastika!” I joked. She laughed and said, “Is that where we are?”

She and I talked about pulling our kids from the school and decided against it. I don’t think I’d sleep any better knowing I’d raised a kid to retreat from his identity, even if for no other reason than he’d get to rightfully tell his therapist his mother was hysterical. This is a lesson faced by all Jews, throughout history. Take the mezuzah off your door and be safe or keep it up and teach your children to be proud of who they are, as they advocate for the safety of all kids, and understand that retaliatory brutality is antithetical to everything we hold sacred as Jews.

The Political Strategist Attacked for Wearing a Keffiyeh

Ashish Prashar: My son’s favorite playground rotates, but for the past month, it has been Edmonds Playground in Fort Greene. He loves it because he gets to run around — he’s 18 months old and really energetic. We go every day. Last Tuesday morning, I was wearing my keffiyeh when we went. Before we left, my son ran into the basketball court because he saw a kid playing there. This kid must have been 7, maybe 8, and he was shooting hoops from the free-throw line. And my baby runs up to him. The kid saw him and started talking to him. It was really cute. Babies love big kids. They’re kind of in awe of them.

Then this woman walked over to me from a bench on the opposite side of the court. She said, “Do you support Hamas? Do you know they’re terrorists?” I was like, “Okay, I’m not gonna have this conversation.” I’m here playing with my son, and I sense this is someone who doesn’t want to have a rational conversation. Then she said, “You and your son are terrorists. Get away from my child.” I was like, “Okay, look, your son was playing with mine.” She got the other boy — I later found out she was his nanny — to move to the other end of the court and told me to get out of the park.

I was like, “I’m not leaving.” She said, “You don’t belong here.” She’s screaming it: “I’m Jewish American, and you don’t belong here!” As a person of color, when they add “American,” I know what that means — it doesn’t mean just the playground. She screamed it a couple more times and got quite in my face about it. She said, “All Arab people are dogs. And do you know your people burn babies in ovens? I hope someone burns your child in an oven.” My son is always running around like crazy, but when she was shouting, he was not moving. He felt something was wrong.

I slowly moved as far away as possible from her, making sure my son was behind me. She was still shouting, so I got my camera out. I started taking a video. Then she stormed over and threw her cell phone at me and my son, followed by her hot tea, which clipped my shoulder. It was a full tea, it was heavy, and I knew it was hot because some of it splattered on me. She hit my phone, told me not to record her. I kept recording.

There were a few other people in the park. One guy came over and stood by the court fence and asked if I was okay. And he stayed there. I think that’s the only reason she didn’t attack me further. He kindly walked me and my son to my front door, which is a few blocks away from the park. The first day we went back, people from our community came with us. I know that’s not going to continue all the time, but people have focused a lot of their energy on making sure we are okay. I’ve had thousands of messages from people saying, “Sorry this happened.” That’s really what New York is.

I know why she attacked me. She attacked me for both the color of my skin and the keffiyeh I wear. And just a side note — I’m not Arab. I worked for Tony Blair when he was Middle East peace envoy. I worked on economic projects in Ramallah to help the West Bank economy. The scarf was gifted to me by a Palestinian woman because we did work with her local business. That was in 2011, and you’ll have seen it around my neck basically every year since then. There are pictures of me that go way back — the 2012 Olympics, the birth of my baby. He has even slept in the scarf; it was a kind of baby blanket for him. I also wear it because I want liberation for Palestinians. I will always wear it.

— As told to Sangeeta Singh-Kurtz

Four Israeli Veterans, Watching the War from Afar

By Nia Prater

When the war between Israel and Hamas began, four Israelis veterans living in the city were forced to watch from the sidelines. While they haven’t been called up from the reserves, they are doing what they can: raising funds Stateside, talking to their comrades, and reaching out to each other. This is how they’ve experienced the past two months 5,000 miles from home.

After October 7, My Orthodox Family Became Unrecognizable

By R.B.

The other day, my mother called me “Hitler.” Someone who wanted all Jews to lie down and die, who thought all Jews were parasites. The war, she said, was because of people like me — self-hating Jews like me. I had commented that killing 4,000 children in a month was a tragedy, and that was the response — immediate, reflexive. That I, who have kept even the smallest and most obscure fast days and holidays, who have kept kosher all my life, crave Jewish death.

I am an Orthodox Jew in an Orthodox family in a heavily Orthodox neighborhood of New York City, and there are constant events — vigils, Shabbat dinners with empty seats at tables for the hostages, rallies in support of Israel — which my family members attend. There are upcoming missions to Israel, neighbors and friends flying there to give what help they can to relatives who are displaced or have spouses on the front lines. There is genuine suffering and a protective shell of anger around it — anger that so many people deign to have opinions on the slaughter in Gaza and a conviction that any opposition to it comes solely from antisemitism. There is antisemitism everywhere, which makes it worse. The paranoia is palpable in my community: It seems to come from some ancestral well of fear, the very fear that brought us to these shores in the first place. More of a confirmation of priors, of the hostility of the world, than some new revelation.

Family members are experiencing what I can only term an attenuated form of nervous collapse. Crying in the middle of the day, not sleeping. Dwelling on dark fantasies that combine the past and the present. I had grandparents who survived the Holocaust, just barely, and I have multiple relatives in Israel, some deployed, some left to tend to their homes and families alone. Everyone is a haunted mess, and jingoism appears to be the defense mechanism of choice. The war is the subject of every conversation. Any other topic feels extraneous, even small happy things. I attend Shabbat meals in a cloud of grim silence. It is painful to watch people around me whom I have known for their inquiring minds and strong sense of morality become uncritical flag-wavers, watch them dismiss massacres as disinformation, watch them advocate more and more violence. They treat cease-fire as a dirty word. It is like suddenly being surrounded by génocidaires, seeing familiar and beloved faces melt into Greek-theater masks of rage.

The family chat on WhatsApp is always buzzing. Everyone is in multiple WhatsApp groups: groups for Jewish women, groups in support of Israel, groups for volunteers. I get endless forwards to condemn such-and-such official, to laud Eric Adams, to call for the ouster of still another official, to condemn universities and student groups. There are tweets, IDF fundraisers, critique or praise of public statements, ceaseless petitions. The phones are always going off. More photos. Photos of mutilated children, videos of slaughter. Who could withstand such an onslaught and not be changed?

Two Palestinian Friends, So Many Losses

Noor Elkhaldi, independent creator, 34: It’s not often I’d meet people from Gaza. Moe understands things I’m experiencing in a way that doesn’t require explaining. My parents each have one parent from Gaza. My mom has hundreds of relatives there. She sent me a list of all our family members who have died. Dr. Hammam, the doctor who gave an interview stating he wouldn’t leave his patients at Al-Shifa hospital before he was killed, is my uncle’s brother-in-law. My cousin Dema got married at the end of July — her husband and his family were killed in an air strike. They didn’t even get a chance.

Moe Dabbagh, brand-marketing manager, 32: Both my parents were born and raised there. I lived there as a kid. On my mom’s side, 49 members of our extended family were killed — her cousins she grew up with, their children, their wives. I feel like the least I can do is try to educate people here. That’s been hard — doing it in a way that’s easy for people to digest, that isn’t shaming them for not knowing, while also trying to manage through grief.

N.E.: For years, I tried to make things easy for people. I’m tired of that shit. During this recent aggression, I haven’t had to cut off anyone close to me. One friend said she doesn’t believe social media can make a difference, to which I was like, “Well, that’s both of our jobs.” We know that’s not true. I’ve had non-Palestinian friends educate themselves to the point where I’m like, “Wow, you’re like a historian now.” It is a relief to see.

M.D.: I’ve been trying to be patient about hitting the UNFOLLOW button on a lot of people. A friend’s husband who served in the IDF has been posting a lot of unhinged propaganda about Pallywood — this idea that images of Palestinian suffering are fake. To see adults share this content, which has been debunked … it’s just so irresponsible.

N.E.: I’ve been doxed a few times. When I hear people talk about being scared, I’m so desensitized to it, it’s not even notable. The doxing was done by Israeli lifestyle influencers — they reached out to my agency and tried to get me dropped. But how can I complain? At the end of the day, I have every luxury a human could have: I’m sleeping at night, and I’m not scared. I have electricity. I have water. To even publicly grieve the loss in my family feels selfish. How could I, in good faith, feel bad for myself?

— As told to Danya Issawi

Additional reporting by Paula Aceves, Gili Benita, Chas Danner, Dean Majd, Hana Mendel, and Jacob Moscovitch.