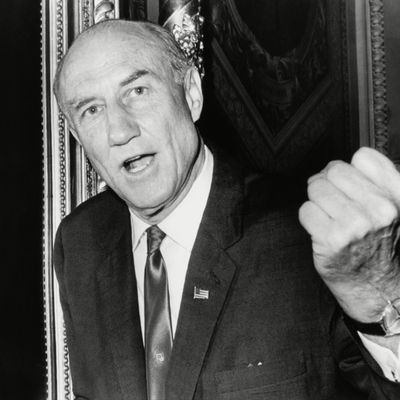

Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell is palpably desperate to preserve the Senate’s legislative filibuster. Last week, he warned that a majority-rule Senate would permit such horrors as the enactment of his own party’s platform. On Tuesday, he returned to the Senate to denounce what he called “a new, coordinated, and very obvious campaign to get liberals repeating the claim that the Senate rules are a relic of racism and bigotry.”

In response to this “coordinated and very obvious campaign” to associate the filibuster with racism, several Republicans are insisting just the opposite. National Review’s Dan McLaughlin and Senator Ben Sasse are echoing McConnell’s talking points. (Your side: engaging in a nefarious coordinated campaign. My side: a bunch of people who happen to agree with each other, saying the same thing at the same time.)

McConnell’s primary argument is that if Democrats actually believed the filibuster is historically associated with racism, they should have allowed Republican bills to pass with just 50 votes. “If our Democratic colleagues really believe what they are saying,” he asks, “did they themselves use a racist tool?” McLaughlin argues, “Democrats such as Warren have happily deployed the filibuster to block new laws themselves hundreds of times in recent years.” “Was the filibuster really a tool of Jim Crow when it was used against Tim Scott last year?,” asks Sasse. “If somebody wants to come to the floor and repent of their racism for having used the filibuster last year, please do.”

Obviously, there is a huge difference between wanting to change the rules and refusing to follow the rules as constituted. Baseball managers may wish to abolish the designated-hitter rule, but pointing out that they continue to use a designated hitter rather than sending their pitchers to the plate hardly invalidates their argument. The objection to the filibuster is not that people who use it are immoral but that the rule itself is bad for the country.

McConnell’s allies likewise insist that the filibuster wasn’t created specifically for racist purposes but is merely one tool that was used to protect white supremacy. McLaughlin argues, “Of course, the Senate filibuster has been used to protect segregation and slavery. Lots of the tools of American democracy were used at one point or another to protect segregation and slavery: popular elections, the presidency, the House of Representatives, the courts, free speech, the Constitution, the administrative state, and — perhaps more than any other American institution — the Democratic Party.”

This completely misunderstands the link between racism and the filibuster. The Founders rejected a supermajority requirement in either chamber of Congress, but the filibuster emerged by accident later in the 19th century. At first, it required unanimous consent; the threshold was later reduced to 67 votes and then to 60. But by custom, it was used rarely and almost always for the purpose of blocking civil-rights bills.

This is not merely coincidental. A routine supermajority requirement would have been completely intolerable. Only because it was reserved for bills protecting black people did the majority tolerate its periodic use. The filibuster exception to the general practice of majority rule was a product of an implicit understanding that the white North would grant the white South a veto on matters of white supremacy.

Opponents of even the most massive pieces of New Deal and Great Society legislation did not dare use the filibuster to thwart them. That was the norm. It survived because northern whites believed that social unity and national peace required special deference to the white South.

As Adam Jentleson, a former Senate aide and author of Kill Switch, points out, southern Democrats specifically defended the filibuster on the grounds that it would be reserved exclusively to block civil-rights laws:

When Barack Obama called the filibuster a “Jim Crow relic,” that is the history he meant: a supermajority hurdle that was once permitted only because it would be wielded to suppress black Southerners had evolved into a tool against all kinds of legislation. To be sure, the Senate has carved out several exceptions; budget bills and court appointments can now be passed with a majority.

This means McConnell can accomplish most of what he wants with a majority — tax cuts, judges, and defunding social programs — while his opponents need a supermajority. It took 60 votes to create Obamacare, but the law would have been defunded with just 50.

McConnell and his party have very rational reasons to keep the legislative filibuster in place; those reasons are not racist. But the filibuster is a Jim Crow relic because, if it were not for racism, it would have disappeared generations ago.