There’s a moment that inevitably comes after your insurance company has denied a claim. You’ve read your member handbook and pored over your policy, bills, and explanations of benefits. You’ve asked your primary-care doctor to send a letter to your insurance company. You’ve meticulously tracked and stuck to your appeal deadlines, sent out rafts of documents to various P.O. boxes, and dialed the 800 number on the back of your insurance card half a dozen times. And then you check the mail. Where you find yet another denial. Ah, you think, I’m going to lose my mind.

Tens of millions of health-insurance claims are denied in the U.S. each year for all sorts of reasons. Sometimes patients get services during the course of an appointment that aren’t covered on their plan — they go in for a skin check and end up getting a mole removed. Sometimes they fail to get preapproval for a procedure because they didn’t know they had to get preapproval, a long and complicated process in and of itself. Sometimes the insurance company just makes a mistake — someone in a billing department submitted a claim incorrectly, say, with the wrong codes. A lot of people choose not to appeal at all; they can’t figure out how or it’s just too maddening. But for those who do, it’s almost universally an exercise in frustration. Because there are so many different types of health insurance — public and private, employer-sponsored and not, fully funded and self-funded — there’s no standard appeal process, which means patients are left to work out how to do it on their own. And it’s really challenging to get a helpful person on the phone to aid you in sorting through the mess. Major insurers are huge diffuse bureaucracies that employ thousands of claims specialists scattered around the country and, in some cases, the world. “Every time you call, you get another person,” says health-insurance advocate Adria Gross. “Or you get someone who answers the phone in the Philippines.” Unfortunately, it’s actually worth it to try. By some estimates, says Patricia Kelmar, senior director of health-care campaigns for the nonprofit U.S. PIRG, up to 50 percent of patients win their cases. Last year, class-action suits were filed against UnitedHealthcare, Cigna, and Humana for using AI programs and algorithms that allegedly automatically batched claims and wrongfully denied or decreased patients’ care. The very act of initiating an appeal can trigger a chain reaction, flagging a patient’s file so that it’s pulled out of a pile of denials for a second look. “By starting the process, there’s a greater likelihood that a human being is going to look at that claim and make a determination,” says Kelmar.

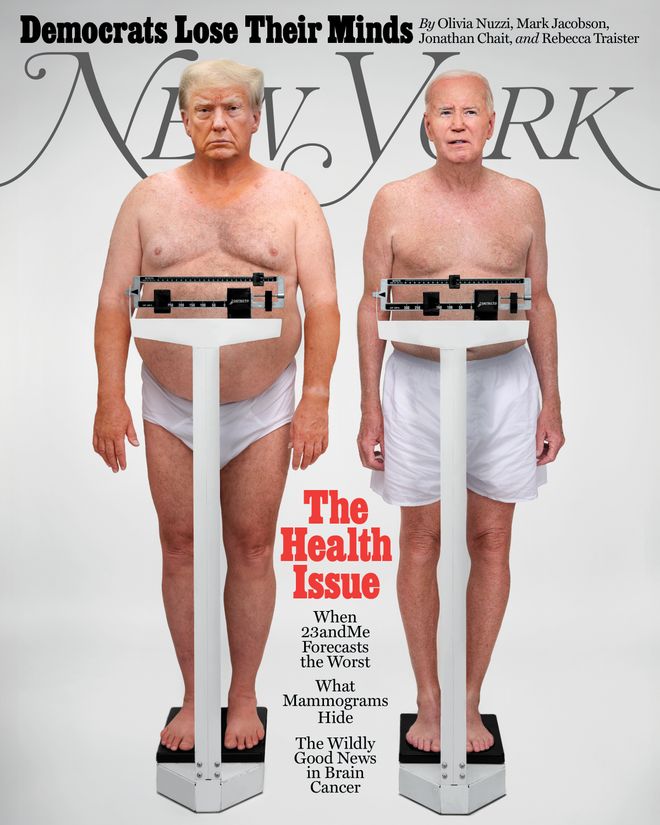

In This Issue

If this all gives the impression that insurance companies overcomplicate the appeals process on purpose to make more money — well, some people think they do. Insurers get to keep the money they don’t pay out on claims, says industry whistleblower Wendell Potter, who left his post as Cigna’s communications VP in 2008. “These companies know that a percentage of people simply will not appeal, often because people don’t think it’s worth the time and effort or just because it is a chore,” Potter says. Even postponing paying claims can benefit an insurance company. When you’re looking at millions upon millions of disputed claims in various stages of adjudication, says Ron Howrigon, a fellow former Cigna executive who started a health-care-consulting firm 20 years ago, “that’s a massive amount of money.” Insurers take these realities into account when they’re making business decisions, Howrigon and Potter believe.

Frustratingly, some of this should have gotten ever-so-slightly better by now. In 2022, the No Surprises Act — a law that protects patients from receiving surprise bills from out-of-network providers — went into effect. The law also requires that health-care providers and insurers give patients EOBs (or AEOBs, for “advanced explanation of benefits”) — what their out-of-pocket costs for nonemergency care would be before they actually receive that care. Having those documents in hand should help consumers anticipate how much it will cost before they go in for that MRI or surgery, which would theoretically help them avoid denials and appeals in the first place.

The problem is two years after the law went into effect, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services still isn’t enforcing the EOB reform. An industry-led working group composed of payers, health providers, and others is drawing up rules for its implementation. But movement on this has been slow. “You can imagine how powerful it would be to know in advance exactly what your insurance is paying for,” Kelmar says. “But we’re all still sitting around, waiting.” Here, four people who successfully challenged their denials.

.

The Doctor Who Found a Technicality

After seeing how difficult it was for her mother to get the end-of-life care she needed, Dr. Georganne Vartorella gave up her career in internal medicine to create her own patient-advocacy firm. Since then, she has helped scores of people successfully appeal their insurance claims. Last year, a severely ill patient at risk of having her colon removed came to her. A specialist had recommended she try weekly infusions of intravenous immunoglobulin, which uses antibodies drawn from the plasma of healthy people to stop the body from attacking itself. Uncovered, IVIg is expensive: Treatment can cost upwards of $100,000 yearly.

I got a phone call from a patient who was beside herself. She had developed autoimmune gastrointestinal dysmotility; she couldn’t get rid of digested food. She consulted a well-known GI specialist. But her insurer wouldn’t pay for the treatment he recommended — even after the specialist, who’s one of the top experts on this disease, wrote an appeal letter. After she called, I reviewed the patient’s insurance policy to see which diagnoses her insurance company would cover the treatment for. Autoimmune gastrointestinal dysmotility wasn’t on the list. But stiff-person syndrome was — the rare neurological disease Céline Dion has, which causes painful, stiff muscles and muscle spasms. My client had never been given a stiff-person diagnosis. But her medical records showed that she’d had symptoms consistent with it.

I couldn’t give her a diagnosis because I no longer practice. But her primary-care doctor could. So I called him to see what he thought. He agreed, and he referred her to a neurologist, who confirmed the diagnosis — opening the door for my client to be able to get her therapy covered. —Georganne Vartorella, M.D.

.

The Daughter Who Wrote a Particularly Good Letter

Soon after Robert Daniels, 66, was diagnosed with ALS, his neurologist tipped him off to a study about a new combination therapy that wasn’t yet FDA-approved. One of the elements in the therapy was a supplement he could order online, and the other was a generic medication he could fill at the pharmacy. But Robert’s insurance plan wouldn’t pay for the generic drug. Until his daughter, Nicolette Andolfo, 39, got involved.

I remember being at his house and seeing one of his EOBs. He was paying about $2,000 a month for the drug out of pocket and had already spent $14,000. My dad was no longer able to work at his hvac company, and my stepmom had retired to take care of him. To start my dad’s appeal, I followed the instructions on his EOB. It was denied, so something called an “external appeal” was his final shot. For that, I wrote a personal letter to the Connecticut Insurance Department, citing the results of a just-published New England Journal of Medicine study of the drug and explaining why it was so critical. I tried to be professional but honest about what my father was up against: “I want him to be able to enjoy the time he has, free from the burden of trying to shoulder the exorbitant cost of the medication that may allow him to extend that time.” Then I attached the NEJM study and sent it. Attaching the study seemed to work. I was shocked when we won. From that point on, the treatment was covered. My dad even got reimbursed for some of the money he’d already spent out of pocket. —Nicolette Andolfo

.

The Mom Who Leveraged a Lawyer’s Template

For the past nine years, Melissa D., 52, has had to battle her insurance company to get her severely autistic, nonverbal adult son’s weekly intensive applied-behavior-analysis therapy covered. Jacob, now 28, started ABA when he was 6. After years of trial and error, Melissa knows how much therapy her son needs to be stable. In 2015, her insurance started trying to cut Jacob’s therapy hours.

ABA therapy is critical for Jacob. The summer we started it, he was still in a diaper. He was also hard to control. But by the end of the summer, with the help of ABA, Jacob was potty-trained and much calmer. After my husband switched jobs in 2015, and we got new insurance, getting Jacob pre-authorization for his ABA was initially smooth. Then the insurance started giving us trouble. Jacob wasn’t making enough progress, they said. We knew Jacob needed six hours of one-on-one care five days a week — but they wanted to cut the hours down to 12 per week. I stumbled onto a nonprofit that helps people with problems like ours. I started working with an attorney who knew state and federal insurance law inside and out and put together an amazing appeal. We worked with him for four years and won every time. Finally I said to our lawyer, “Look, if you give me the letter you use, I think I can take it from here.” He agreed, and I’ve been handling the process since. To make sure Jacob gets his hours, we need to reapply for prior authorization every three to six months. We always expect a denial. To prepare for those denials, I make an appointment with Jacob’s primary-care physician, scheduled before the decision comes — the appeal requires a current prescription for his therapy and a record of his most recent physical. Then I contact his ABA therapists to make sure all of his info is accurate and up to date so they can write out a progress report for him, a treatment plan, and an explanation as to why the treatment is medically necessary. Then I write a letter using the lawyer’s template, which cites a lot of state and federal law, as well as our insurance plan’s schedule of benefits and member handbook. —Melissa D.

.

The Parent Who Tracked Down a Clerical Error

Five months after the birth of her daughter, Sasha Lazare, 33, received a notification from her insurer, Oscar Health: Oscar was refusing to cover Sasha’s early induction, alleging it wasn’t medically necessary. The costs hovered around $85,000. Sasha hadn’t wanted to deliver early, but she’d had no choice; her doctor had ordered it. After her midwife sent Oscar her complete medical file, which included more information on her induction, she didn’t hear from the company again. She assumed it was resolved, but then, last fall, she got a new bill for $1,844.60.

After my midwife helped me overturn my claim rejection in 2021, I never heard from Oscar again. I switched jobs after that, and we got new health insurance. So when I got this bill last fall, I had no idea what it was for. It wasn’t itemized. I had lost access to my Oscar portal after I switched, so I couldn’t see whether it was related to the original rejected claim. One of my new employee perks is having access to a health advocate. I called that person and asked for help to see what was going on. It took her months of going back and forth between the hospital and Oscar, but finally she helped us figure out what we now believe was the root of the problem: Someone at the hospital had gotten my daughter’s date of birth wrong when they filed the claim for reimbursement. She was born on December 18. Someone had put December 23, the day her birth certificate was printed. So I think the hospital messed up — though the hospital seemed to think it was Oscar’s fault. Either way, the health advocate told us that the outstanding bill was actually legitimate because when I had given birth, we hadn’t yet met our deductible. Somehow, though, the advocate managed to get someone at the hospital to cut the bill in half — if I paid in 24 hours. —Sasha Lazare