These days, Americans can’t escape rising prices. Go to the grocery store for some pork, and you’ll pay nearly 5 percent more than you did last spring. Go to the gas pump, and filling your tank will damn near empty your wallet. Check out that open house down the street, and you’re liable to see an asking price 15 percent higher than you thought it would be. Take a drive down to the lumber yard to buy yourself a new pet log, and it might cost you 400 percent more than last year’s.

And if you turn on the TV to escape thoughts of such sticker shock, you’re liable to see newscasts full of inflation talk.

For consumers and policy-makers alike, a defining question of our economic moment is this: Are today’s price rises the start of a lasting trend that will lower living standards and derail the economy, or merely the birth pangs of the post-COVID recovery (if not this century’s roaring ’20s)?

No one can answer that question with certainty, but the available evidence does tilt in one direction. Here’s a quick rundown of why inflation is rising, what will happen if it keeps doing so, and the case for (and against) thinking that you’ll be using dollar bills for napkins this time next year.

Why inflation is rising.

In April, inflation in the U.S. rose at its fastest pace since 2009, with the consumer price index (CPI) increasing at a 4.2 percent annual rate. That was significantly higher than economists had expected. Futures of global commodities integral to economic growth — including oil, gasoline, corn, and copper — now cost twice as much now as they did a year ago. And Americans weren’t alone in facing such sharp price hikes: Across the developed world, prices rose 3.3 percent in April, the swiftest jump since 2008.

In the U.S., this spring’s spike in inflation has (at least) five clear causes:

1) Consumers have cash to burn. Prices rise when the demand for goods and services outstrips their supply. So you can’t have consumer-price inflation if consumers don’t have money to spend. And right now Americans are flush with cash.

This is strange! Typically, recessions do damage to household balance sheets. In an ordinary economic downturn, unemployment goes up and wage growth goes down, forcing many to dip into their savings or take on debt to make ends meet. For this reason, in the early stages of an economic recovery, consumers (as a whole) are too concerned with restoring lost savings and paying off loans to make discretionary purchases at their prerecession levels.

But the COVID recession was atypical — and so was the government’s response to it. The pandemic effectively forced Americans to increase their savings rate by preventing them from safely indulging in myriad forms of consumption (concertgoing, dining out, travel, etc.). Meanwhile, Congress supplied the economy with trillions of dollars in fiscal support, including $3,200 in direct cash assistance to most American workers, and generous income-replacement for the unemployed. A significant minority of Americans were nevertheless financially devastated by the pandemic. But the majority who lost neither their jobs nor income in 2020 collected thousands of dollars from Uncle Sam, and saved nearly as much (if not more), thanks to their newfound shut-in lifestyles. As a result, U.S. households are in better financial shape after a plague lay waste to their economy than they were at the peak of the preceding economic expansion.

After a typical recession, demand takes a while to catch up with the restoration of supply. Now, we’re seeing the opposite.

2) Going on vacation or out to eat is much more appealing now than it was at the onset of global plague. The airline, hotel, and restaurant industries were all hammered by the pandemic. As public-health-conscious Americans have become vaccinated en masse, these sectors have gotten caught between surging demand (since travelers and diners are trying to make up for lost leisure) and inadequate supply (since it takes time to rebuild businesses decimated by a full year of depressed patronage). This has yielded price hikes: The average price of an airline ticket was 10.2 percent higher in April than it had been a year earlier, while that of a hotel room was 8.8 percent higher, and a meal away from home was 3.8 percent more expensive.

It’s important to note, however, that those prices rose from an exceptionally low baseline; there was little demand for vacations and reservations last spring. Between February 2020 and May 2020, airline prices fell by 30 percent, and hotel room rates by 14 percent. Even with April’s price surge, the cost of airfare and lodging remains below pre-pandemic levels.

The sudden expansion in consumer appetite for dining out has also contributed to rising meat prices. During the pandemic, meat producers adjusted to a world in which cooking was in and fine dining out, by packaging a high percentage of their wares in cuts designed for grocers. Now, restaurants are in a bidding war for the remaining meat supply, as they seek to stock their walk-in refrigerators at levels commensurate with full dining rooms. The end result is higher prices for beef and pork both on the menu and in the grocery aisle.

3) Global supply chains haven’t recovered from COVID yet. The global market for key production inputs and commodities is similarly out of whack. Semiconductor manufacturers scaled back production last year due to weak demand, even as car producers began pivoting toward electric vehicles. Now, the global economy is suffering from a severe shortage of chips. That forced U.S. carmakers to slow production in April, which in turn drove up the price of used vehicles. At the same time, rental-car companies that had liquidated their fleets last year amid a collapse in travel all started trying to replenish their inventories at once, putting further upward pressure on used-car prices. A similar dynamic holds for the lumber industry. The 2008 crash wiped out a lot of the world’s sawmills, and COVID slowed production at those that remained. Now, with interest rates low — and, after a year trapped inside, many Americans newly conscious of their current home’s deficiencies — lumber producers can’t keep pace with demand.

The global-shipping industry is also disoriented. The combination of pandemic-induced disruptions to supply chains and booming demand for consumer goods, as affluent households the world over cut back on services and ramped up online ordering, has yielded a shortage of shipping containers, which has pushed transport costs to their highest level since 2010. And that’s making just about every imported good a bit more expensive.

4) The Colonial Pipeline hack has left behind durable gas shortages. This factor doesn’t explain April’s increase in energy prices, which was rooted in a combination of last year’s low baselines, elevated demand, and high transport costs, among other factors. But last month’s cyberattack on a pipeline that facilitates nearly 50 percent of the East Coast’s fuel supply is still driving up gas prices. As of last Thursday, nearly one-fourth of all gas stations in the Carolinas were still suffering fuel outages, while 12 percent of all fueling stations in Florida remained disabled.

5) Low-wage workers are finally getting raises. Full-service restaurants saw no inflation in April, but fast-food establishments jacked up prices significantly. That partially reflects elevated meat costs, but it’s also indicative of a long-belated increase in low-wage workers’ bargaining power. In the first quarter of this year, wages rose by 3 percent for private-sector workers, the strongest quarterly wage gain since the 1990s.

Some of those pay gains went to perennially coveted “high-skill” professionals. But a significant portion ended up in the pockets of the working class. With their savings buttressed by stimulus checks — and, for the previously laid off, their sustenance assured by $300-a-week federal unemployment benefits — many American workers have become newly empowered to turn down lousy job offers. This, combined with resurgent demand, has produced a shortage of labor in some sectors, forcing firms to raise wages to attract new hires. Last week, McDonald’s announced that it’s raising wages for hourly workers at company-owned stores by 10 percent, while Chipotle will lift its entry-level pay rate to $15 an hour by the end of June.

What happens if today’s inflation becomes a long-lasting trend?

There’s no debate about whether America is experiencing significant inflation. But a short-term increase in prices would be no big deal; in fact, it might even be a good thing, since inflation has been excessively low over the past decade.

The question is whether today’s price increases are the beginning of lasting trend, or the product of a temporary mismatch between demand and supply, as the economy adjusts to post-COVID crisis conditions. The Federal Reserve, the government entity most responsible for tracking inflation, endorses the latter hypothesis. But some economists disagree.

If inflation does prove durable, the nightmare scenario would be something like this: Consumers’ expectations for price increases don’t remain anchored to past experience (which, for millennials like myself, includes no period of high inflation), but instead adjust to a new, heightened baseline. Which is to say, they start expecting their money to lose value at a fast and rising rate. That makes spending your dollars now more appealing than saving them. And yet, if everyone starts spending more at once, too many dollars will be chasing too few goods, and prices will rise even further. That, in turn, will raise inflationary expectations, which will further encourage spending over saving, which will further increase prices, in a vicious cycle. Meanwhile, with so much spending going on, workers will find themselves in high demand, but they’ll also find the real value of their wages falling. So workers who have some leverage — whether due to their skills or their unions or labor scarcity in their fields — will push for wage increases, which will lead employers to raise prices, which will lead workers to demand further wage increases, in an inflationary spiral.

The economy thereby becomes destabilized. Some Americans would benefit from a high-inflation environment, which effectively redistributes wealth from creditors to borrowers, who get to pay back their loans in a depreciated currency. But people on fixed incomes and workers who lack the bargaining power necessary to maintain the real value of their wages would suffer declines in living standards.

All this said, the costs and benefits of a high-inflation environment may be beside the point. The Federal Reserve has an inflation target of 2 percent: If inflation averages far above that number for months on end, the central bank will raise interest rates to choke off the flow of credit and slow spending in the economy. In other words, policy-makers will not tolerate a sustained period of ultrahigh inflation. But interest-rate hikes are a very blunt instrument for lowering the prices. And rapid, large rate hikes would have the effect of increasing unemployment and reducing wages. At the same time, Congress would face great pressure to reduce aggregate demand by cutting spending. A recession could ensue.

The case for concern.

The case for believing that inflation will last longer, and rise higher, than the Fed anticipates includes these four points:

1) Congress’s extension of $300-a-week unemployment benefits only goes through Labor Day. These extended unemployment benefits have simultaneously propped up demand for labor (by ensuring that even the unemployed have some money to spend) while limiting its supply (by reducing the incentive of the jobless to seek work). As a result, firms are being forced to raise wages to attract workers. Those wage hikes could spill into prices. At which point, firms might need to raise wages even more to attract job applicants, potentially producing a self-reinforcing inflationary pressure.

2) Supply-chain disruptions might be less temporary than many assume. As former fund manager Richard Cookson writes for Bloomberg: “Company inventories are at rock bottom. Every corporate survey, including this week’s manufacturing and non-manufacturing ISMs, shows huge worries about rising costs. The same is true of services.”

3) Long-term structural trends are less deflationary than many think. The Fed’s comfort with current inflation is premised, in part, on the fact that there’s been a long-term trend toward deflation in the global economy. After the 2008 crisis, central banks had so much trouble generating enough inflation, they had to hold interest rates near zero (or even below). Inflation doves argue that this environment was born of structural forces that aren’t going anywhere — such as technological advance, the globalization of the labor market, and aging populations (old people buy less stuff than young ones) — and therefore, gravity will eventually bring prices back down to earth. Inflation hawks counter that price increases were quite robust in the U.S. service sector before the pandemic. Headline inflation may have been low, anyway, due to the falling price of manufactured goods. But with global supply chains heavily damaged, and shipping costs durably elevated, deflation in tradable goods may cease to compensate for price growth in the service sector. And that hypothetical looks all the more likely when one considers that service-sector businesses (1) will have an incentive to make up for last year’s losses by raising prices this year, and (2) will have greater ability to raise price, since many of their competitors went out of business during the pandemic, and:

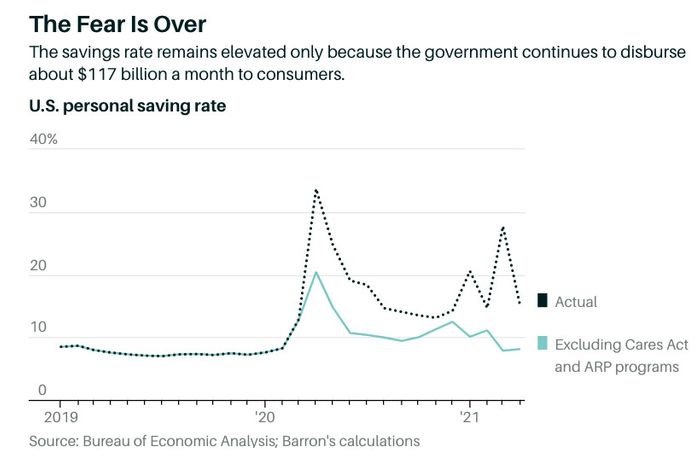

4) Consumers are loaded. As we saw above, Americans have a lot of cash in their bank accounts, thanks to COVID-era stimulus packages. To this point, unusually high savings rates have muted the impact of all this spare cash. But as life returns to normal, the savings rate is, too.

5) Congress is likely to authorize more deficit spending in the coming months. Joe Biden’s economic agenda comes with a roughly $4 trillion sticker price. That spending is doled out over a period of eight years, and he says that he intends to offset every dollar of it with tax increases. But if recent history is any guide, Congress might well paper over its internal disagreements with new Treasury bonds. And anyhow, Biden’s proposed tax increases are all aimed at the very rich, whose rates of consumption aren’t very sensitive to marginal changes in their tax liabilities.

Why the post-COVID inflation spike will (probably) be temporary.

The argument for believing that the current rate of price increases will be temporary, and that inflation will stabilize at a non-problematic level, looks stronger than the alternative. The doves’ case can be broken down into five parts:

1) A supermajority of April’s inflation derived from spikes in industries hammered by the pandemic. Nearly 60 percent of April’s consumer price increase came from just five categories — used cars, rental cars, airfare, lodging, and food away from home. In normal times, these items comprise little more than 13 percent of the CPI. As we saw above, demand for these goods and services was decimated by the pandemic, and, thus, prices are rising from a ridiculously low baseline. The fact that, in the wake of mass vaccination, the price of a hotel room is rising precipitously, but still hasn’t quite returned to its pre-pandemic norm, should not raise much concern for long-term inflation. And much the same can be said for the other four categories.

2) Wage pressures are (unfortunately) likely to ease come the fall. America’s unemployment rate remains near 6 percent. Wages are rising, but not to any remarkable extent. The pre-pandemic era was characterized by tepid wage growth and record corporate profits. Thus, there’s reason to think that pay rates can rise quite a bit further without triggering massive price hikes, as labor secures a less-flimsy share of the value it produces.

In any case, the main driver of workers’ present bargaining power — the $300-a-week federal unemployment benefit — will disappear come October. The American labor movement remains exceptionally weak. Tight labor markets could put some upward pressure on wages. But the era in which large portions of the workforce enjoyed the benefit of collective bargaining agreements with cost-of-living adjustments — such that any increase in prices would automatically increase their pay — is long dead.

3) Prices in some hot sectors are already self-correcting. For inflation to take off, consumers must permanently revise their expectations for prices. Otherwise, when a given good or service gets too costly, people will stop buying it, and prices will fall. In one of the economy’s hottest sectors, housing, that doesn’t appear to be happening. As Bloomberg’s Conor Sen recently noted:

The July lumber futures contract has fallen by 25 percent from its May 7 peak, a sign that the market has found a level where buyers are balking rather than continuing to pay up. And for the first time since buying surged last spring, the inventory of homes for sale has increased for two consecutive weeks, a sign that normal seasonality might be returning.

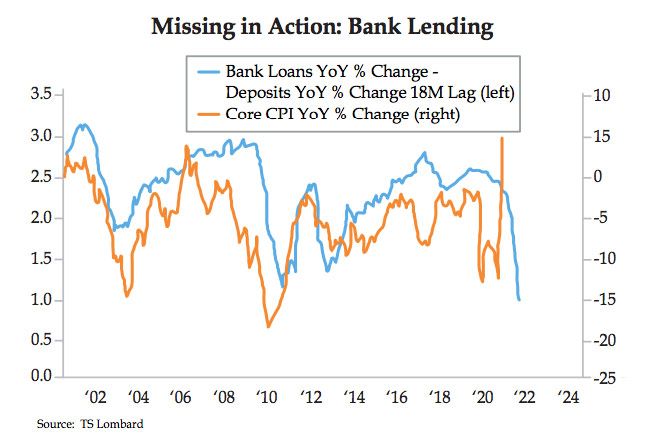

4) Banks aren’t playing their part. One key ingredient in the recipe for runaway inflation is abundant credit. To sustain demand for overpriced goods, consumers need to have ready access to loans. Historically, periods of inflation have witnessed sharp increases in bank lending. Today, trends are pointing in the opposite direction: Americans are paying down debts, and the rate of bank lending is falling.

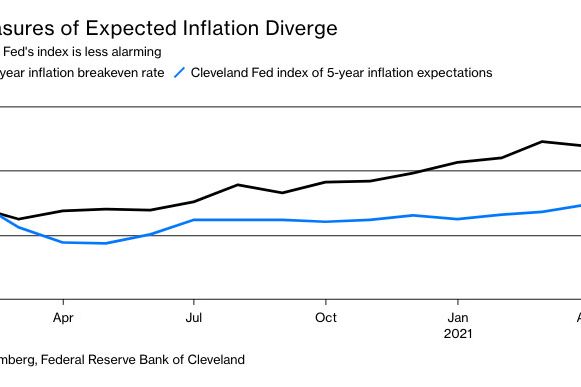

5) Inflation expectations remain modest. There are two go-to measures of inflation expectations: The break-even rate on five-year Treasury bonds, and the Cleveland Fed’s index of five-year inflation expectations. The former derives from the gap between the interest rate that investors demand on ordinary five-year Treasury bonds, and the one they accept on five-year Treasury bonds that are protected from inflation. The disparity between those yields is, more or less, the market’s consensus view of what average inflation will be in the coming five years.

At present, that break-even rate sits at about 2.4 percent. That’s only a bit higher than the Fed’s target. The central bank has said that it wants inflation to run above its 2 percent target for a little while, so as to compensate for a decade of undershooting. Further, some economists have argued that the optimal inflation target is actually 4 percent.

Regardless, the Cleveland Fed’s index remains well below 2 percent. And there’s reason to put greater trust in its projection. The Treasury break-even rate is composed of a single variable, and one that is influenced by market factors that have little to do with inflation. The Cleveland Fed index, by contrast, synthesizes a wide array of market and survey data.

Whether one accepts the high or low projection, the five-year outlook for inflation doesn’t look like a problem.

The debate over inflation’s likely trajectory isn’t academic. If policy-makers come to believe that today’s price growth will be durable, then they will prioritize “cooling off” the economy over minimizing unemployment. That would benefit wealthy Americans who have more to lose from rising prices than from mass joblessness. But it would hurt the working class — which depends on tight labor markets to secure significant wage gains — and condemn the most vulnerable laborers in the country to perpetual unemployment. On Capitol Hill, meanwhile, an anti-inflation consensus would likely doom much of Joe Biden’s economic agenda. Which is to say, a lot of analysis of the outlook for inflation is informed by the political and class interests of the analysts themselves. The one you’ve just read is no different.

But I’ve tried to summarize the available evidence impartially. And if all I’ve given you is my own two cents, well, at least the price was right.