Last week’s devastating wildfires on Maui killed at least 96 people, and authorities say death toll will continue to rise. The wildfires are the worst natural disaster to strike Hawaii in nearly eight decades; and the deadliest wildfires in the U.S. in more than a century. President Biden has declared a major disaster in Hawaii and firefighters on Maui are still working to contain several blazes and flare-ups, while more than a dozen federal agencies have been mobilized to assist with the recovery. On Saturday, FEMA estimated that it would cost more than $5.5 billion to rebuild. Below are updates on this developing story.

Death toll rises to 96, but most of the victims remain unidentified

Maui County officials announced on Sunday night that the confirmed death toll from the wildfires on the island had risen to 96. Federal workers, service members, and local and state authorities continue to search the burned down homes and buildings and burned out vehicles in the ruins of Lahaina, which before the fires was home to about 13,000 people. Hundreds of people remain unaccounted for as of this weekend, and relatives of the missing have been asked to submit DNA samples to authorities.

Only two of the victims in West Maui had been identified as of Saturday. Many relatives of those missing after the fires are still waiting for answers, per the New York Times:

For days now, families have struggled to learn the status of loved ones in West Maui. Spotty-to-nonexistent phone reception, especially in the immediate aftermath, made it hard for survivors to contact loved ones. Roadblocks prevented people from other parts of the island from looking themselves. … Interviews and social media posts make clear that large numbers of people with ties to Maui endured days of uncertainty about the status of friends and loved ones.

As of Saturday, the wildfire’s death toll eclipsed that of the horrifying Camp Fire, which killed at least 85 people in Northern California in 2018. The West Maui disaster is now the deadliest U.S. wildfire since the 1918 Cloquet Fire in northern Minnesota, which consumed several communities and killed more than 450.

Honolulu City Beat has compiled a list of ways to donate to support survivors and victims’ families here.

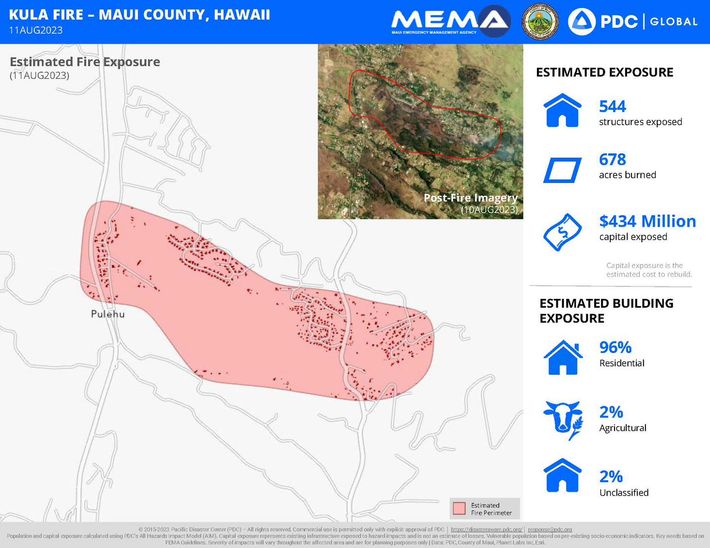

Mapping the damage

On Friday, the Pacific Disaster Center (PDC) and FEMA released some maps detailing the damage done by the Lahaina Fire and Kula Fire in West Maui (note that in both fires, the vast majority of the structures damaged or destroyed were residential):

Why did people have so little warning about the coming inferno?

Hawaii has a state-wide emergency alert system — including the largest number of outdoor sirens in the world — developed in the aftermath of a tsunami which killed more than 150 people in 1946. But according to the Associated Press, many survivors of the Maui wildfires have said they received no official warnings. The emergency sirens were not activated, and though emergency alerts were sent out to people’s mobile phones and using television and radio broadcasts, many in danger may not have received the alerts amid the cellular and power outages. In addition, some of Maui’s top emergency officials were not on the island on Tuesday, Honolulu Civil Beat reports:

Neither Maui’s fire chief nor its top emergency management official were on the Valley Isle on Tuesday despite the wildfires there being well underway. Further, on Thursday county officials couldn’t or wouldn’t say when or if the evacuation order for Lahaina was issued or how those plans had unfolded two nights earlier when fire swiftly consumed the town[.]

Maui’s fire chief, Bradford Ventura, said in that press briefing that the fire reached Lahaina so quickly that residents of the first neighborhood it hit “were basically self-evacuating with fairly little notice.”

“The fire that day was so quick, it moved so quickly, that from where it started in the brush and moved into the neighborhood, communications back to those who make those notifications, was physically nearly impossible,” the Maui chief said Thursday.

Hawaii Attorney General Anne Lopez announced Friday that her office would be conducting a “comprehensive review” of the government response to the emergency with the goal of “understanding the decisions that were made before and during the wildfires and to sharing with the public the results of this review.”

17 people were rescued from the water in Lahaina

The Coast Guard said Friday that it had rescued 17 people from the ocean near the devastated town on Tuesday evening and early Wednesday morning. It had initially received reports of as many as 100 people in the water. One person, described as unresponsive, has been pulled from the water since then.

The conditions that fueled the wildfires can and will happen again elsewhere

Dr. Nick Bond, the state climatologist for Washington, explains in an interview:

Grasses can dry out a lot faster than big trees. What really made the fires bad was the grasses having dried out quickly. And those grasslands are especially dangerous because their fires can advance really quickly. A forest-fire rule of thumb is that the fire front moves at about one-tenth of the wind speed, but grassland fires are a lot faster than that. You don’t have to wait for a tree to catch on fire and then have the embers be lofted up and new fires set ahead. It’s a process for forest fires. But with grasslands, the fire can advance almost as fast as the wind.

He also noted that there are other parts of the U.S. where there are currently similar conditions that could foster this kind of fire:

On the latest drought maps, there are fairly serious drought conditions in parts of Texas and in the southern Great Plains. Those are going to be more grassland-type fires. I’m not sure how much it’s on the radar, but another spot people think is pretty wet but definitely has fire problems is Florida. Their wet season in most parts of the state is in the summer, so it’s at the end of the winter that they’re really prone to that.

Read the rest of what Dr. Bond had to say here.

Lahaina is gone

The historic West Maui town of Lahaina — a popular tourist destination and once the capital of the Kingdom of Hawaii — was largely reduced to ashes by a fast-moving wildfire that struck on Tuesday. Hawaii governor Josh Green toured the town on Thursday and later told reporters it looked as if it had been flattened by a bomb. He estimated that at least 1,000 buildings were destroyed.

Maui County mayor Richard Bissen Jr. said on Friday morning that the community looked like a war zone. “It was cars in the street, doors open, melted to the ground. Most structures no longer exist. And from blocks and blocks of this,” he said.

The Lahaina wildfire was 80 percent contained as of Friday morning.

Dozens of people were killed in the town, and it’s not yet clear how many are still missing. Officials have estimated that 1,000 residents remain unaccounted for but explained that with communication systems down, many of the missing may simply be unable to get in contact with their loved ones.

The unique challenges of the recovery effort

Governor Green estimated that the wildfires had undoubtedly caused billions of dollars in damages on Maui, and as Honolulu Civil Beat reports, numerous overlapping factors will hamper the recovery attempts:

The recovery is likely to be complicated by the destruction of infrastructure. Green noted that the fire had incinerated utility poles in the area. As a result, fully restoring electricity would take weeks or months rather than days, as it might after a storm …

Also delaying recovery is the fact that Maui is a less populous island in a remote island state. Robert Fenton, FEMA’s Region 9 administrator, likened the Maui fire to wildfires such as a 2018 blaze that destroyed much of the town of Paradise, California. He said the scale of destruction reminded him of the Mississippi Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina. But a major difference, he said, is the ability to respond. On the mainland, he said, it’s possible to quickly “muster 3,500 dump trucks” to move rubble. “I just can’t do it here,” he said.

Green said he is considering calling for a special legislative session to provide state money for Maui’s recovery. In the meantime, he said, people can tap into federal FEMA funds relatively quickly, for housing and home repairs.

A mass exodus of tourists

Nearly 15,000 visitors left Maui by plane on Thursday, and while the rest of the state remains open to tourists, authorities have asked would-be travelers to avoid the island.

The fire moved so fast that some Lahaina residents had to flee into the ocean

Winds fueled by a hurricane traveling hundreds of miles south of Hawaii have amplified the wildfires in Maui, the second-largest of the state’s islands. Conditions on Maui’s western side got so bad on Tuesday that around a dozen residents of the charred town of Lahaina were forced to flee the fires by jumping into the ocean, where they were rescued by the Coast Guard. At least six people were killed in the town and two dozen more were injured.

“911 is down,” Lieutenant Governor Sylvia Luke told CNN. “Cell service is down. Phone service is down. Our hospital system on Maui, they are overburdened with burn patients, people suffering from inhalation.”

Gusts of up to 80 miles per hour were reported on Tuesday, closing roads and making evacuations more difficult. High winds also grounded helicopters, so it was impossible to fight the fires from the air or accurately gauge the size of two primary blazes, one in the tourist destination of West Maui and the other in a mountainous region farther inland. According to a Maui County official, around 2,000 tourists were stuck at the nearby airport on Wednesday morning. Around 14,500 homes in Maui were without power by early Wednesday night, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency approved a disaster declaration to respond to the crisis. The Hawaiian National Guard has also been deployed.

As Hurricane Dora travels roughly 500 miles south of the Hawaiian islands, the Category 4 storm has created massive gusts that fueled the brush fires. While a high-pressure system north of Maui was expected to ease conditions on Wednesday, local officials were stunned by the speed of the wildfire’s spread and its connection to the hurricane. “When we deal with hurricanes and disasters following hurricanes, we’re usually dealing with heavy rain, we’re dealing with flooding,” Luke told CNN. “The fact that we have wildfires in multiple areas as a result indirectly from a hurricane is unprecedented; it’s something that Hawaii residents and the state have not experienced.”