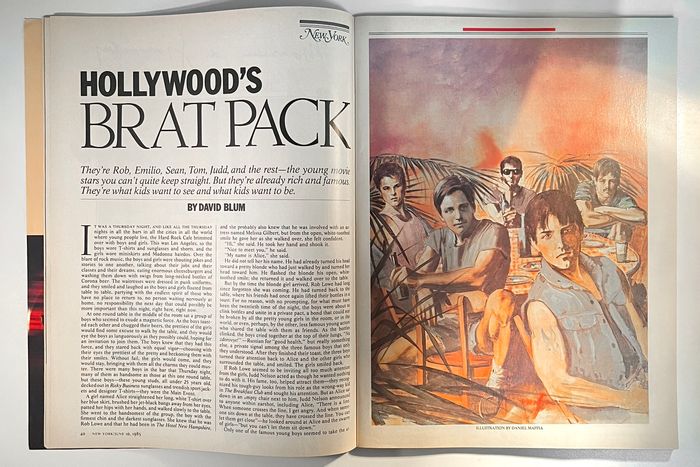

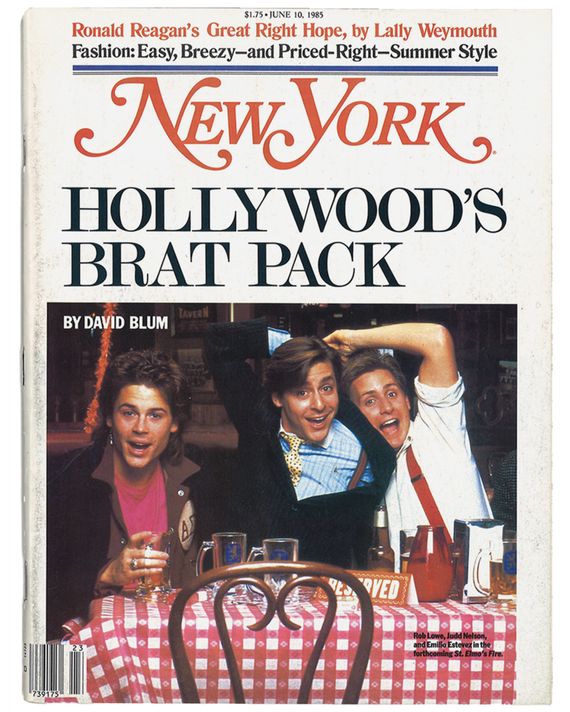

Editor’s note: “Hollywood’s Brat Pack,” by David Blum, first appeared in the June 10, 1985, issue of New York Magazine. In June 2024, Brats, Andrew McCarthy’s documentary about our story, the actors it grouped together, and its aftermath premiered at Tribeca Film Festival before streaming on Hulu. Forty years and a documentary later, Blum is sticking by his definition of the cohort.

It was a Thursday night, and like all the Thursday nights in all the bars in all the cities in all the world where young people live, the Hard Rock Cafe brimmed over with boys and girls. This was Los Angeles, so the boys wore T-shirts and sunglasses and shorts, and the girls wore miniskirts and Madonna hairdos. Over the blare of rock music, the boys and girls were shouting jokes and stories to one another, talking about their jobs and their classes and their dreams, eating enormous cheeseburgers and washing them down with swigs from long-necked bottles of Corona beer. The waitresses were dressed in punk uniforms, and they smiled and laughed as the boys and girls floated from table to table, partying with the endless spirit of those who have no place to return to, no person waiting nervously at home, no responsibility the next day that could possibly be more important than this night, right here, right now.

At one round table in the middle of the room sat a group of boys who seemed to exude a magnetic force. As the boys toasted each other and chugged their beers, the prettiest of the girls would find some excuse to walk by the table, and they would eye the boys as languorously as they possibly could, hoping for an invitation to join them. The boys knew that they had this force, and they stared back with equal vigor—choosing with their eyes the prettiest of the pretty and beckoning them with their smiles. Without fail, the girls would come, and they would stay, bringing with them all the charms they could muster. There were many boys in the bar that Thursday night, many of them as handsome as those at this one round table, but these boys—these young studs, all under 25 years old, decked out in Risky Business sunglasses and trendish sport jackets and designer T-shirts—they were the Main Event.

A girl named Alice straightened her long, white T-shirt over her blue skirt, brushed her jet-black bangs away from her eyes, patted her hips with her hands, and walked slowly to the table. She went to the handsomest of the group, the boy with the firmest chin and the darkest sunglasses. She knew that he was Rob Lowe and that he had been in The Hotel New Hampshire, and she probably also knew that he was involved with an actress named Melissa Gilbert, but from the open, white-toothed smile he gave her as she walked over, she felt confident.

“Hi,” she said. He took her hand and shook it.

“Nice to meet you,” he said.

“My name is Alice,” she said.

He did not tell her his name. He had already turned his head toward a pretty blonde who had just walked by and turned her head toward him. He flashed the blonde his open, white-toothed smile; she returned it and walked over to the table.

But by the time the blonde girl arrived, Rob Lowe had long since forgotten she was coming. He had turned back to the table, where his friends had once again lifted their bottles in a toast: For no reason, with no prompting, for what must have been the twentieth time of the night, the boys were about to clink bottles and unite in a private pact, a bond that could not be broken by all the pretty young girls in the room, or in the world, or even, perhaps, by the other, less famous young actors who shared the table with them as friends. As the bottles clinked, the boys cried together at the top of their lungs, “Na zdorovye!”—Russian for “good health,” but really something else, a private signal among the three famous boys that only they understood. After they finished their toast, the three boys turned their attention back to Alice and the other girls who surrounded the table, and smiled. The girls smiled back.

If Rob Lowe seemed to be inviting all too much attention from the girls, Judd Nelson acted as though he wanted nothing to do with it. His fame, too, helped attract them—they recognized his tough-guy looks from his role as the wrong-way kid in The Breakfast Club and sought his attention. But as Alice sat down in an empty chair next to him, Judd Nelson announced to anyone within earshot, including Alice, “There is a line. When someone crosses the line, I get angry. And when someone sits down at the table, they have crossed the line. You can let them get close”—he looked around at Alice and the swarm of girls—“but you can’t let them sit down.”

Only one of the famous young boys seemed to take the attention in stride—perhaps because he grew up the son of a famous actor, Martin Sheen. Just 23 years old, Emilio Estevez looks like his famous father and is a star on his own; he played the young punk in Repo Man and the jock in The Breakfast Club. His sweet smile of innocence drew still more women to the table, and he could not resist them.

“She was a Playmate of the Month,” he whispered as an exotic-looking young woman in a purple jumpsuit took the seat next to him and smiled like an old friend. “The last time she was here, we were telling her about a friend who had passed the bar exam, and she said, ‘I didn’t know you needed to take a test to become a bartender.’” He laughed at her stupidity. But then he turned his attention to her, and before long, the toasts were over. Rob Lowe went back home to his girlfriend, waiting for him in Malibu. And at 1:35 A.M., after leaving the Hard Rock and stopping at a disco and then an underground punk-rock club, Judd Nelson took off by himself in his black jeep. Emilio Estevez and the Playmate went off together into the night.

This is the Hollywood “Brat Pack.” It is to the 1980s what the Rat Pack was to the 1960s—a roving band of famous young stars on the prowl for parties, women, and a good time. And just like Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, and Sammy Davis Jr., these guys work together, too—they’ve carried their friendships over from life into the movies. They make major movies with big directors and get fat contracts and limousines. They have top agents and protective P.R. people. They have legions of fans who write them letters, buy them drinks, follow them home. And, most important, they sell movie tickets. Their films are often major hits, and the bigger the hit, the more money they make, and the more money they make, the more like stars they become.

Everyone in Hollywood differs over who belongs to the Brat Pack. That is because they are basing their decision on such trivial matters as whose movie is the biggest hit, whose star is rising and whose is falling, whose face is on the cover of Rolling Stone and whose isn’t. And occasionally, some poor, misguided fool bases his judgment on whose talent is the greatest.

The Brat Packers act together whenever possible—and it would be a major achievement for the average American moviegoer not to have seen at least one of their ensemble movies over the past four years. The first Brat Pack movie was Taps, the story of kids taking over a military school, a sleeper that took in $20.5 million. Then came The Outsiders, adapted from the S. E. Hinton novel and directed by Francis Ford Coppola; Rumble Fish, another Coppola-Hinton effort; The Breakfast Club; and now, on June 28, the release of the latest matchup of the Brats, St. Elmo’s Fire.

Emilio Estevez is the unofficial president of the Brat Pack. (He is also the unofficial treasurer; other members seem to forget their wallets when they go out together, and Estevez usually picks up the check.) He may get his best notices yet, for his role in St. Elmo’s Fire.

“I’ll bet if you asked everyone in the cast who their best friend is,” says Joel Schumacher, who directed and co-wrote St. Elmo’s Fire, “they’d all say Emilio. He’s that kind of guy.”

Here are the rest:

The Hottest of Them All—Tom Cruise, 23. He first made his mark in Taps, then went on to star in the youth-movie classic Risky Business. The huge success of that movie (it made $30.3 million) gave Cruise the leverage to get over $1 million per movie.

The Most Beautiful Face—Rob Lowe, 21. He first showed it to moviegoers in The Outsiders, then starred in Class and The Hotel New Hampshire. He stars in St. Elmo’s Fire.

The Overrated One—Judd Nelson, 25. He made his reputation as a hood in Making the Grade and The Breakfast Club. And now, in St. Elmo’s Fire, he shows—with his role as a congressional assistant—that he was better off when typecast.

The Only One With an Oscar—Timothy Hutton, 24. He got started ahead of the others as a troubled teen in Ordinary People, then joined the Brat Pack in Taps. Fellow Brats whisper that he’s made one too many flop (Turk 182! was its name) and now must revive his career or risk being forgotten.

The One Least Likely to Replace Marlon Brando—Matt Dillon, 21. Everyone thought he would do it back when he made Tex and The Outsiders, but he eased into a lower gear with The Flamingo Kid, a comedy that did well at the box office.

The Ethnic Chair—Nicolas Cage, 21. A nephew of Francis Ford Coppola, he changed his famous surname—and took out an eyetooth to play a leading role. Birdy, which made his reputation as an actor. His ethnic looks usually land him the part of brother or best friend.

The Most Gifted of Them All—Sean Penn, 24. He is the natural heir to Robert De Niro’s throne; like his mentor, Penn will transform himself for any role he takes. The results have been awesome: from the surfer Jeff Spicoli in Fast Times at Ridgemont High to the drug dealer Daulton Lee in The Falcon & the Snowman.

Not Quite There: the Two Matthews—Broderick, 23, and Modine, 24. Both are fine actors—Broderick in WarGames and on Broadway, and Modine in Birdy—but both live in New York. The Brat Pack likes them but doesn’t know them. The same goes for Kevin Bacon, 26, the star of Footloose and Diner.

What distinguishes these young actors from generations past is that most of them have skipped the one step toward success that was required of the generation of Marlon Brando and James Dean, and even that of Robert De Niro and Al Pacino: years of acting study. Young actors used to spend years at the knee of such respected teachers as Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler before venturing out onstage, let alone in movies; today, that step isn’t considered so necessary.

No one from the Brat Pack has graduated from college—most went straight from high school into acting. Rob Lowe, Sean Penn, and Emilio Estevez all went to Santa Monica High School and acted as much as they could. Estevez made 8-mm. movies that he acted in and directed; he and Penn wrote and co-starred in one movie about Penn stealing Estevez’s dog. Penn later directed a play that Estevez wrote and starred in at Santa Monica High, about Vietnam veterans.

Estevez shares a show-business upbringing with several other Brats; Sean Penn is the son of Leo Penn, a director of such television programs as Magnum, P.I. Tim Hutton is the son of the late actor Jim Hutton; and Nicolas Cage’s connection to Coppola led to his first film part, in Rumble Fish. Tom Cruise grew up in the East, away from the world of Hollywood; still, he found he didn’t need much training to succeed.

They all admire the work of those actors who spent years in diligent training, but they do not consider De Niro and Brando, or even Martin Sheen, role models for their careers. There is a spiritual father of the Brat Pack, but it is not an established star, nor is it Frank Sinatra or Sammy Davis Jr. or Peter Lawford. It is a grizzled 58-year-old character actor named Harry Dean Stanton. He has been a familiar face around Hollywood and a cult hero among film buffs since the 1960s, but has only lately become a real success, as the star of Repo Man (with Estevez) and, most recently, Paris, Texas. The Brats admire Stanton for his acting gifts—but they have befriended him for his ability to relate to them as kids, sometimes partying with them all night and sleeping till noon.

Stanton lives up in the hills above Hollywood, in a house from which one sees nothing but trees and hawks. As he sits in his living room dressed in an old bathrobe (“This once belonged to Marlon Brando,” he remarks), he says of these young stars, “I don’t act like their father, I act like their friend.” Rubbing sleep from his eyes, he thinks for a minute and then adds, “Boy, would I have loved to have had everything these guys have when I was 22. That would have been great.”

It was a hot spring night in Westwood, perfect weather for moviegoing, and the leader of the Brats wanted to see Ladyhawke, which stars Matthew Broderick. But it would not behoove one of the Brats to fork over $6 to the industry that made him a star to begin with. So Emilio Estevez stood outside the Mann’s Village Theater, five minutes to show time, considering the various ways he might be able to get into the movie free.

“I have a friend who works here who’ll get me in free,” Estevez said, but as he eyed the man taking the tickets of the paying customers, he muttered, “Guess he’s not working tonight.” After a moment’s thought, he said, “If I could get to a phone, I think I know something I can do.”

And so, with three minutes left, Estevez marched down the nearest street in search of a phone. He peered into a pinball parlor and asked, “Do they have a phone in here?” They did not. He walked down to a parking lot and heaved a sigh of relief. “There’s a phone,” he said, and trotted off to use it. He called the theater and explained that he was Emilio Estevez and that the friend who normally let him in free wasn’t working tonight; would there be any way to get Estevez passes for the eight o’clock show? Of course, he was told, and when he arrived, the manager and the ticket taker welcomed him to the theater and told him how much they loved his movies. “Thank you,” Estevez said, and with a smile, he dashed off to catch the opening credits.

Estevez, who is only five foot six, stands as a vivid prototype of the Brat Pack he seems to lead. Barely 23 years old, he is already accustomed to privilege and appears to revel in the attention heaped upon him almost everywhere he goes. He has a reputation in Hollywood as a superstud: Dozens of girlfriends, many of them groupies, latch on for brief affairs; his romance with actress Demi Moore (who is also in St. Elmo’s Fire) is off and on. He is living the life that any American male might dream of—to be young, single, and famous.

But the Brat Packers are smart, and Estevez, perhaps the smartest of all, recognizes that with his fame and fortune comes a responsibility to preserve them. So he works hard at his profession, building a substantial résumé of acting credits to keep him going. His career began at eighteen, with an afternoon television special, Seventeen Going On Nowhere. By the time he had made his fourth feature, The Breakfast Club, he was 21. It was during the filming of The Breakfast Club that Estevez became a protégé of one of the most powerful young talents in Hollywood: writer-director-producer John Hughes. Returning to his condo in Malibu after the making of The Breakfast Club. Estevez wrote a screenplay called Clear Intent. It wasn’t his first screenplay—that one, an adaptation of an S.E. Hinton novel called That Was Then, This Is Now, has since been made into a movie with Estevez as the star and will be released this fall. But Clear Intent was surprisingly sophisticated, and when he showed it to Hughes, the reaction was so positive as to assure him a career as screenwriter.

“When I was reading it, I thought it was so good, so close to my bone, that I had written it,” said Hughes the other day, granting a brief interview over his car phone on his way to work. Only five years ago a Chicago-based humor writer, Hughes now has a multi-million-dollar deal with Paramount Pictures for his next several projects; one of them, Hughes said, may be Clear Intent. “Emilio wants to direct it, and I’m sure he will be able to,” Hughes said. “He can do anything. He can act, he can write, he can direct. He’s surpassed me in that respect. I can’t act—I wish I could.”

Clear Intent is the story of two L.A. garbagemen who witness a murder and unwittingly get involved. Who will play the garbagemen? “Maybe Judd Nelson could play one of the parts,” said Estevez one day. Another day he said, “Boy, I would love to play one of them.” At still another moment, he asked, “Do you think Matthew Broderick would be believable as a garbageman?” and then added, “Sean Penn would be good.” And what about Nicolas Cage? “Yeah, I’ve been thinking about him; he’d be great.” There appears to be little doubt: Clear Intent will unite at least two Brats onscreen once again.

It was almost midnight on a boys’ night out, and Judd Nelson and Emilio Estevez were still looking for some fun. So Estevez summoned a young writer he’d always wanted to meet, Jay McInerney—the author of a book, Bright Lights, Big City, that he’d once wanted to option and turn into a screenplay. It was 1984’s trendiest novel, and McInerney was staying at one of Los Angeles’s trendiest hotels, the Chateau Marmont, revising the first draft of the screenplay of his book. Coincidentally, the man set to direct the film version of the book is Joel Schumacher—the director of St. Elmo’s Fire.

McInerney showed up at the Hard Rock at around 11:30 P.M. in a sport jacket and mostly unbuttoned shirt. Estevez was wearing a T-shirt and chic black sport jacket with flecks of color. Nelson was wearing a gray jacket, a dark tie, a gray pullover, and a shirt almost hidden from view. It was 65 degrees, but he did not appear to be sweating. They all shook hands, with McInerney looking slightly mystified that he had been invited. The three of them, along with the Playmate, got into two cars, with McInerney in the backseat of Estevez’s Toyota pickup truck, and drove to Carlos ’n Charlie’s, a restaurant-discotheque on Sunset Boulevard. The coat-check girls recognized the movie stars and waved the group in without collecting a cover charge.

Estevez wandered around the club, and Nelson went to the dance floor, where the tune of the moment was “ABC,” by the Jackson Five. Nobody seemed interested in talking to McInerney. Nelson walked up to one of the loudspeakers and started dancing directly in front of it. But no one was dancing with him, and it was too dark for anyone to notice that there was a movie star dancing with a loudspeaker. So after a few minutes, the anonymity appeared to be too much for him; he sat down with a dejected look and started complaining about what a horrible club it was. Then he suggested they leave.

“There’s a punk club open tonight across the street,” he said. “Let’s go.” So Estevez and Nelson and the Playmate and McInerney paid the check and left.

Across the street was the Imperial Gardens Japanese restaurant. Late at night, the Japanese restaurant mysteriously disappears, and a punk club takes its place. A long line snaked through the entranceway and out the door, and two large bouncers stood at the foot of a long staircase to the club, not letting anyone inside.

“Some people have no shame about such things,” Estevez said when it was suggested that he approach the bouncers and inform them that two movie stars would like to get in. “I have shame.” And so he made no movement. But the rest of the people in line began to notice him and Judd Nelson, and a murmur reached the bouncers.

“The manager would like to speak with you,” said one of the bouncers, who left his spot at the staircase to speak to Estevez. And so Estevez put away his shame and headed over. Moments later, he waved his group toward him; the manager stamped their hands, showing proper awe. “I guess we’re not as important as they are,” muttered a girl standing at the front of the line as Estevez, Nelson, McInerney, and the Playmate made their way inside, please with their clout.

McInerney, somewhat of an expert on nightclubs—his book is filled with tales of late-night New York crawl—remarked upon entering the crowded club that there did not seem to be a VIP lounge on the premises. Estevez nodded and bemoaned the hordes around the bar. In New York, celebrities typically are ushered into private rooms, served free drinks, and photographed by paparazzi, who will place their pictures in the next day’s editions of the dailies.

The Brats will be coming to New York this month to promote St. Elmo’s Fire, which all of them seem rather obsessed with. Each new Brat Packer movie carries with it an increased burden–if it is not a success, the young unknowns starring in the hit movie of the moment might come up from behind and replace them. And that would mean the end of the kind of ensemble efforts that created the Brat Pack.

“I think ensembles should continue forever,” says Judd Nelson. His name is being tossed around for one of the leads in Bright Lights, Big City—Tad Allagash, a suave young gadabout. The other role has been cast; the character based on the book’s author will be played by Tom Cruise. Aside from Judd Nelson, the other actors under consideration for the role of Tad are Emilio Estevez and Rob Lowe.

Estevez and Nelson did not, however, learn anything about the character from talking to McInerney the other night. After summoning him to their late-night cruising, and shouting a few comments to him over the din at the Imperial Gardens, the Brat Pack took off and left McInerney at the club. He walked back to his hotel by himself.

The leader of the Brat Pack ordered two slices of pepperoni pizza and a Coke at Lamonica’s N.Y. Pizza stand in Westwood, the home of UCLA and, seemingly, the capital of the generation that buys all the movie tickets. There is an enormous movie theater at practically every intersection in Westwood; movies that have long since closed elsewhere are still playing here. So for Emilio Estevez to show his face in this neighborhood was to invite the stares of countless fans, and as he wolfed down his slices, the rest of the customers watched in silent respect.

Moments after he’d sat down, a lanky, greasy-haired young man approached the table.

“Hey, Emilio, how you doin?”

Estevez looked up expecting a fan, but the man he saw standing above him was another member of the Brat Pack—Timothy Hutton.

“Hey, Tim, how you doin?”

“Not bad, man, how you doin?”

“Okay dude. What are you up to?”

“Not much. How about you?”

“Nothin’.”

Pause

“You seen Sean?” Hutton was referring to Sean Penn.

“No. I heard he was at the party for Madonna the other night, Sunday or Monday,” Estevez said.

“Oh…well, take it easy dude.”

“Okay…so long, dude.” Hutton and a small entourage of young men about his age and greasiness walked back through the pizza joint and into the kitchen for an unknown purpose. And Estevez explained that he and Hutton don’t know each other very well. “We met through Sean,” he said.

The Brat Pack whispers that Hutton has made a near-fatal mistake; he has made movies that have failed at box office. For one of the pack, this is a mortal sin—because what makes you a member, what makes you a Brat, is the ability to be in a position where Hollywood needs you more than you need Hollywood. “Tim’s last three movies were bombs,” one of the Brats noted, in a not-for-attribution remark. “It’s going to get to the point where the Oscar isn’t going to matter. If you can’t sell tickets, that’s it.”

And this is why Estevez’s best friend, Tom Cruise, is so hot these days—and why he can afford to be perhaps the biggest Brat of all, at least insofar as the movie industry is concerned. He broke out of the pack with Risky Business and can now command not only a colossal salary but such perks as casting approval and script consultation, things bigger stars couldn’t dream of getting a decade ago.

Cruise, Hutton, and now Estevez, with his plans to be a screenwriter-director, all stand as inspiration to junior members of the Brat Pack yearning for a place in the sun, for the clout to pick and choose among the hundreds of parts now available for actors under the age of 25. They are competing, too, for the attention the media has heaped upon the Brat Packers; and it is no coincidence that Estevez and Cruise share the same press agent, Andrea Jaffe of the PMK agency, who guards their reputations with the same zealous fervor she devotes to such elder clients as Farrah Fawcett—keeping their reputations clean but also keeping them hot.

“This word ‘hot,’” says Judd Nelson, who switched just recently to PMK. “‘Hot.’ ‘Hot’! You can be ‘hot’ and be a shamelessly poor actor. It’s possible, now it’s possible to be at the top for half a second and then disappear. It’s such a strange thing, to try to build a career on this heat.”

And yet that is precisely what they do. For actors so imbued with the ensemble spirit, the Brat Pack members are out for themselves. “Sean is crazy with all of his role preparations, becoming the character in every way,” one says. And of Andrew McCarthy, one of the New York–based actors in St. Elmo’s Fire, a co-star says, “He plays all his roles with too much of the same intensity. I don’t think he’ll make it.” The Brat Packers save their praise for themselves.

The crowds had arrived at the Hard Rock. It was about 11 P.M., and the Brat Pack was in full swing—on their fifth or sixth round of Coronas, and their ninth or tenth round of toasts. The small circle of stars had expanded to include several young actors of their acquaintance, not to mention the dozens of girls who continued to hover near the table.

One of the young actors was Clayton Rohner. He seemed to have most of the credentials necessary to join the Brat Pack: the kind of looks, attitude, and presence that suggested acting talent. He seemed especially ebullient—and the reason, no doubt, was that he was celebrating his first starring role in a movie, something that might bring him closer to the exalted status of his friends. But the film, called Just One of the Guys, didn’t fit into the same league as The Breakfast Club—it was merely another teen exploitation flick, perhaps a little better than average, but still not up to par with those of the Brats.

And so, when a young girl of about sixteen approached him with a pen and slip of paper, asking him for an autograph, Rohner looked immediately at his more famous friends with a skeptical grin. “One of you put her up to this, right?” he asked. They all smiled and denied it. “C’mon,” he said, looking at the girl. “One of these guys told you to do this. Which one? I know one of them did.” But the girl looked back at Rohner with that special look, the puppy-dog gaze of a groupie who has finally come face-to-face with her fantasy. “Please,” she said, thrusting the piece of paper ever closer to him. He took the pen and, with a flourish, signed his name for the girl. As he finished, he looked up again at the members of the Brat Pack. “I know you guys made her do this,” he said.

But the Brat Packers just shook their heads and watched, without the trace of a smile, and suddenly it was clear that they were as surprised as he was to see the girl leave the table with his autograph, smiling to herself, not bothering to get theirs too.