(I) We were attacked because we were Americans—not because we were New Yorkers, or we were rich, or our politics favored a diverse society—but to the terrorists themselves, “America” remained vague and abstract. The nineteen hijackers had no feeling for our culture and society and only the most general objections to it. When they did think about America, it was as a certain kind of dupe, an overmuscled husk through which more malevolent forces moved, some of them having to do with capitalism or Christianity but most having to do with Israel. In Hamburg, as their cell arranged itself, the terrorists were all in agreement that Monica Lewinsky had been a Mossad operative, deputized to seduce President Clinton. When Ramzi Yousef was planning the World Trade Center bombing in 1993, he told an associate that he had first hoped to attack Israel but decided it was “too tough a target” and so had settled on our country instead. The fatwas that Al Qaeda’s spiritualists issued against the United States were full of the perfidies of our policy in the Middle East—the “Zionist-Crusader alliance,” the interference in Saudi and Egyptian politics—but had almost nothing about the content of our national character, the shape of our society. Next to nothing about women, or about narcissism or excess, or about the compulsive aspects of our infatuation with youth and modernity. In the aftermath of the attacks, we told ourselves that it must have been the things that made America exceptional—our freedoms, our liberal culture—that provoked this murderous aggression. And though this was never precisely true, it was—given everything that has followed—a propulsive misconception.

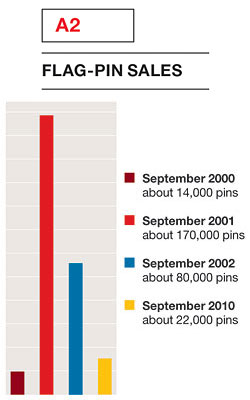

(II) Within the United States, the political unity that existed briefly after the attacks was soon squandered, but a deeper unity, at a level of identity, remained: Both liberals and conservatives were Americans first, again [A2]. A certain conviction soon took hold that we as Americans must somehow have been betrayed by the advertisements for ourselves, as if some unscrupulous ad firm, entrusted with the “America” account, had performed sloppy work and then overbilled. If we were hated, then it was because we were misunderstood. For conservatives, as the cultural critic Susan Faludi has documented, America had been “Oprah-ized,” softened and feminized— “the impotent America,” George W. Bush told Bob Woodward in 2002, describing the misimpression the Clinton years had given bin Laden. “A flaccid, you know, kind of technologically competent but not very tough country.” Bush vowed virility. But along with the armies he sent to the Muslim world, he also sent a non-Arabic-speaking advertising executive, equipped with videotaped testimony from Muslim-Americans, to promote the notion that the melting pot could incorporate Islam, too. Efforts at cultural evangelism gripped liberals as well. By 2003, it seemed every American music act touring Europe felt moved to apologize for the nation. “Just so you know, we’re on the good side with y’all—we do not want this war, this violence, and we’re ashamed that the president of the United States comes from Texas,” Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks told a London audience.

Years earlier, as the journalist Eric Alterman noticed, Bruce Springsteen, in Paris, told a concert audience that America “held out a promise, and it was a promise that gets broken every day in the most violent way. But it’s a promise that never, ever dies, and it’s always inside of you.” If Bush’s belief was “America is great because of what makes us different,” Springsteen’s was “America is great because we make evident universal human hopes and universal flaws.” In many ways, the politics of the past few years, with the universalist iconography of Obama on one side and a political theater of pining for the Founding Fathers on the other, has remained trapped between these two convictions.

(III) One of these visions now seems more correct than the other. WE ARE ALL AMERICANS, the famous Le Monde headline read on September 12 [A3], and though as a statement of global political unity this was fleeting, it did suggest a more lasting, less sentimental realization: that the distinction between the United States and the rest of the world was eroding. Ten years later, America now looks a bit more like other countries do—our embrace of capitalism has grown more complicated, our class mobility less certain, our immigrants and our diversity less unique—and the Bush era now seems a last, angry assertion of a form of American exceptionalism that the attacks helped undo. In the military and economic disasters that have marked the past decade, it has become obvious to everyone that America cannot simply accomplish anything it wants to. The proof point of American exceptionalism had been our strength. Bin Laden got his metaphor right. He fixed his sights on a towering, singular target that he was convinced was less unique and more vulnerable than everyone else supposed.

A3: Solidarity

“America struck, the world seized by terror,” read the main headline of French daily Le Monde on September 12. On the right ran the editorial titled “Nous sommes tous américains” [We are all Americans].