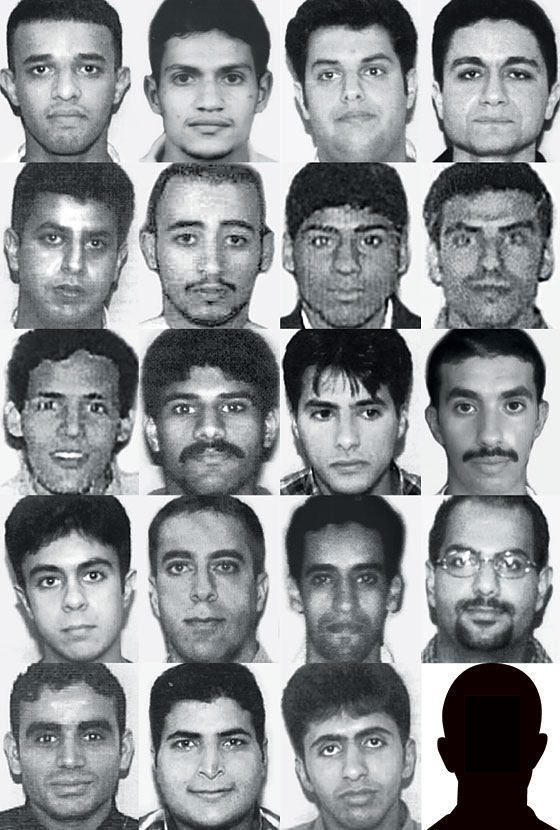

The nineteen arrived in the U.S. at various times, several of them more than a year before the day. Some appeared on government watch lists of suspected terrorists. Nevertheless, throughout their time in this country they moved about freely in a number of states—Florida, Arizona, California, Virginia, New Jersey—and on the morning of September 11, each passed through airport security and onto their planes undisturbed.

The leader of the nineteen was Mohamed Atta, and they were divided into four groups, one for each plane, each with a pilot who served as group leader: Atta, Marwan al-Shehhi, Ziad Samir Jarrah, and Hani Hanjour. Atta, al-Shehhi, and Jarrah had moved to Germany in the nineties to attend separate colleges and met through radical Muslim circles in Hamburg around 1998. Al-Shehhi was already religious when he arrived in Germany but initially struck people as a “regular guy” who wore Western clothes. Jarrah, the son of affluent Lebanese parents, had attended Christian schools and frequented beer-soaked discos in Beirut; he spent all his time in Germany with his girlfriend, a fellow dental student. After returning from a trip home, however, Jarrah began reading jihad brochures and preaching to his friends, later growing a full beard and chastising his girlfriend for her liberalness. The friends hosted anti-American salons and finally traveled to Afghanistan, where they met Osama bin Laden, who recruited them as the attacks’ primary facilitators.

Bin Laden named additional recruits, directing them back to Germany and then to the U.S. to begin flight training. More than a year before the attacks, one named Nawaf al-Hazmi found himself stranded in Southern California when his partner tired of America and returned to Yemen. Al-Hazmi could not speak English and complained about how hard it was to meet people around Los Angeles; he secured a job at a gas station and used the Internet to search, unsuccessfully, for a wife. Hanjour, an observant Muslim who’d gone to Afghanistan as a teenager in the late eighties to fight the Russians, had traveled in the U.S. extensively, studying English at the University of Arizona in 1991. He joined al-Hazmi in December 2000, and the two relocated to Arizona, where they commenced flight lessons. Hanjour’s instructors found his skills poor, but he nevertheless completed his instruction, and in the spring of 2001, the pair ultimately headed east, to Paterson, New Jersey, to await the arrival of the “muscle hijackers”—those who would storm the cockpits and control the passengers.

During the summer and early fall of 2000, bin Laden began selecting the muscle hijackers, who were in fact physically unimposing and stood between five foot five and five foot seven. Twelve came from Saudi Arabia; most were recruited into jihad in their neighborhood mosques or universities. Some had planned to fight in Chechnya but encountered difficulties crossing the border and were diverted to Afghanistan, where they heard bin Laden’s speeches and joined his camps. All were between 20 and 28; several were unemployed, while five had begun university; two were brothers; all but one were unmarried. Not all were religious; at least two liked to drink.

After training in Afghanistan—including butchering sheep and camels to practice knife skills—most of the muscle hijackers settled near Atta in rentals around Southern Florida. (The owner of the Panther Motel in Deerfield Beach found Atta and the few others who stayed there with him to be polite. While they gawked at women in bikinis gathered around the motel’s kidney-shaped pool, they draped a towel over a picture in their room of a bare-shouldered woman.) Most bought memberships to local gyms, where South Floridians in Spandex chuckled from their ellipticals as the future hijackers awkwardly threw dumbbells around. A man who rented two of the men apartments likened them to guys you’d take to a baseball game. When he asked for a forwarding address, one promised to send him a postcard.

In the meantime, as September approached, the Hamburg pilots began taking cross-country surveillance flights in the type of planes they would fly. Two arranged practice flights through the Hudson Corridor, the low-altitude “hallway” that passed the WTC; once again, a flight instructor noted Hanjour’s poor flying skills and refused to take him up a second time. In the weeks before September, Hanjour and Atta met twice in Las Vegas, where they may have finalized plans. Al-Shehhi also traveled there, visiting the Olympic Garden Topless Cabaret in downtown Vegas, where a 29-year-old with crimped blonde hair recalled giving him a lap dance; he paid her the requisite $20, no tip. In this proclivity, he was apparently not alone; strippers in clubs around Daytona Beach, including the Pink Pony, remembered servicing some of the men. Starting in the last week of August, nineteen tickets were bought for the four September 11 flights, some from a Kinko’s in Hollywood, Florida. A few days before the attacks, Atta and al-Shehhi spent hours at Shuckums, an oyster bar in Hollywood, where they drank Captain-and-Cokes and Stoli screwdrivers, played video Trivial Pursuit and blackjack, and spoke loudly to each other in Arabic. The bartender worried al-Shehhi might leave without paying his $48 tab; when a manager approached him, al-Shehhi pulled out a wad of cash and said, “There is no money issue. I am an airline pilot.”

While Atta forbade the hijackers to make contact with their families, he called his father days before the attacks. Just after midnight on September 9, Jarrah was issued a speeding ticket in Maryland. The next day, he wrote a letter in Arabic to his girlfriend in Germany: “Do what you were meant to do, keep your head up, but with a goal, never without a goal … Always remember who and what you are. Stay strong, winners always carry their heads up high!” For reasons unknown, Atta and another hijacker drove a rental car from Boston to Portland, Maine, where, on the night of September 10, they made ATM withdrawals, ate pizza, and shopped at a convenience store. In the early-morning hours of September 11, at the Comfort Inn outside Portland, they donned button-downs and slacks and slipped collapsible knives into their pockets. Surveillance cameras at the Portland airport recorded them proceeding through security, after which they boarded a commuter flight to Logan airport, where they joined their three fellow hijackers in business-class seats aboard American Airlines Flight 11.

While attending the Technical University of Hamburg, Mohamed Atta studied urban planning and wrote a thesis titled “Neighborhood Development in an Islamic-Oriental City,” in which he argued that “the traditional structures of the society in all areas should be re-erected.” Daniel Brook, who explored Atta’s academic background in a three-part series for Slate, noticed something else about the document: “The highways and high-rises are to be removed—in the meticulous color-coded maps, they are all slated for demolition.” The only known copy of Atta’s document is in the possession of his thesis adviser, professor Dittmar Machule, who keeps it under lock and key.