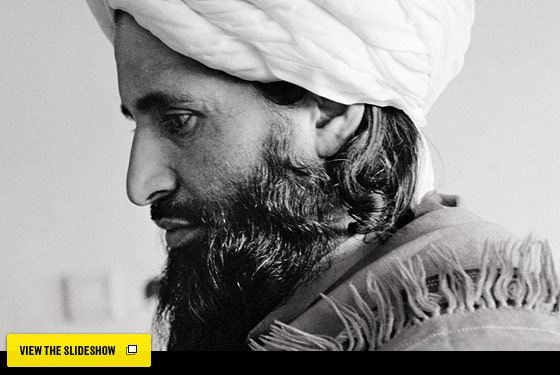

September 11 broke open a generations-long battle raging inside Islam over who has the right to speak for the faith. On one side is the Islamic religious Establishment, embodied by the scholars who gather behind closed doors to debate theology. On the other, the self-proclaimed reformers of a diversifying global community of 1.6 billion (four fifths of whom don’t reside in the Middle East), determined to apply the tenets of their faith to worldly problems. Like it or not, Osama bin Laden presented himself as one such reformer, and his plot against America, says No God But God author Reza Aslan, only accelerated a transformation of Islam.

Long before 9/11, the leading scholars had lost much of their legitimacy, in some cases due to their support for corrupt and unpopular authoritarian regimes. Armed with a new confidence in their personal authority, believers turned to reading and interpreting the Koran for themselves, exponentially expanding the points of view on scripture and doctrine. In that way, modern Islam is “very, very Protestant,” says Kecia Ali, author of Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam. “There’s a do-it-yourself mentality, which is as relevant to fundamentalists as it is to feminists.” (Ali is a white American convert to Islam who happens to also be a leading scholar on early Islamic law—a mixed bag of identities unthinkable 100 years ago but increasingly common now.)

What some, though not Ali, would term the Islamic Reformation shares attributes with Evangelical Christianity. Both the Muslim and Christian revivals are calls to return to an idealized past, when God spoke directly to his people and principles of right and wrong were clear and simple. Both have been fueled by the desire to cast worldly corruption out of religion. This has led to such disparate forms of Islam as Nigeria’s Pentecostal Muslims and the Afghan Taliban.

But beginning on September 12, 2001, Al Qaeda’s methods forced Muslims to confront the violent jihad waged in their name. As the United States responded to the attacks with wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and drone strikes in Pakistan, some took the resulting massive Muslim death tolls as evidence of a global crusade against Islam, led by America, in which Islamic terrorism was a justified tactic. But the rise of militancy forced the silent majority of Muslims—as common to Islam as to any other religion—to take ownership over their faith, to say the extremists do not speak for us. One result has been a new progressive engagement among legal advocates over what Islamic law should be for the 21st century. Another has been a newfound conservatism, both in America and abroad, that’s seeking a way of protesting Western hegemony without turning to violence.

Until an impoverished Tunisian fruit seller set fire to himself this past January and set off a chain of rebellions across the Muslim world, Al Qaeda’s brand of militancy remained the best-known form of dissent against corrupt regimes. But now there’s evidence that Twitter may prove more effective in the long run than a rocket-propelled grenade. “Social media gives a lie to AQ,” says Amir Hussain, a professor of theological studies at Loyola Marymount University. In the same way that 9/11 forced Muslims to take seriously the threat of militant Islam, the Arab Spring has proved that it’s possible to reject Al Qaeda without rejecting Islam as a means of dissent. Meanwhile, the divisions within Islam continue to splinter and re-splinter within the Islamic Reformation’s ever-widening tent.

Eliza Griswold, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation, is the author of The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches From the Fault Line Between Christianity and Islam.