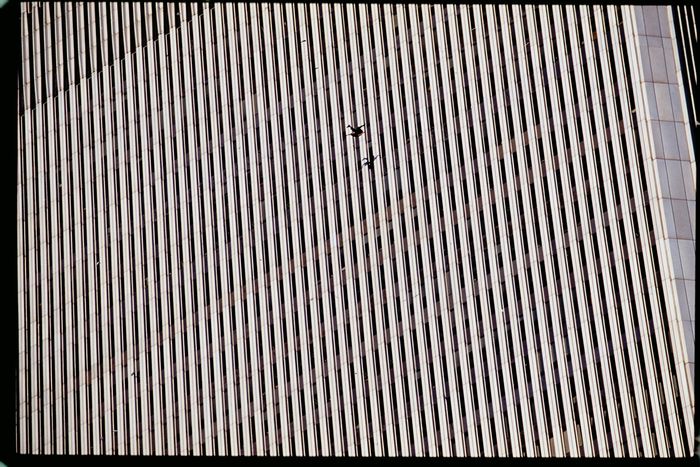

On September 12, 2001, the New York Times printed a photograph that had been taken by Associated Press photographer Richard Drew the previous day; so did newspapers all over the country. It showed a man who, having jumped from one of the burning World Trade Center towers, was falling through the air to the pavement: an acrobatics of death. An estimated 7 percent of those who were murdered on 9/11 died by jumping; there is ample photographic documentation, taken by various witnesses from various angles, of this horrific phenomenon. But the Times never ran Drew’s photograph, or anything like it, ever again; neither did most other American papers. Indeed, photographs of the so-called jumpers have been rendered taboo, vilified as an insult to the dead and an unbearably brutal shock to the living (though they have been printed abroad, and can be found on the Internet). And journalists who have tried to identify the falling, dying man in Drew’s photograph have been met with angry rebuffs by those who might be his family, as Tom Junod documented in Esquire in 2009. One purported daughter told journalist Peter Cheney when confronted with Drew’s photograph: “That piece of shit is not my father.”

The jumper photographs make clear to us the utter vulnerability of the victims; they present us with terrorism as a human experience, not just a political crime. Those trapped in the Towers had only two choices—to jump to their deaths or to be incinerated—which is to say they had no choice at all. To moralize either “choice”—to despise one as cowardly and valorize the other as heroic—is to misunderstand both. What the 9/11 victims faced was the absence of options.

Susie Linfield, a journalism professor at NYU, is the author of The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence.