It is too soon to write about the Jazz Age with perspective,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in 1931, the last time New York had been torn as suddenly from its moorings. “It was an age of miracles, it was an age of art, it was an age of excess, and it was an age of satire … We were the most powerful nation. Who could tell us any longer what was fashionable and what was fun?”

Ten years have passed since the morning assault that gouged our city—they are both a blip and an eon. Premillennial New York was an enclave, as hermetic in its way as the city had been in the twenties, constantly congratulating itself for the lovely, roaring, extravagant business of being New York. The late nineties in New York City was a period when nothing seemed to go wrong, and New Yorkers went right to and through the looking glass.

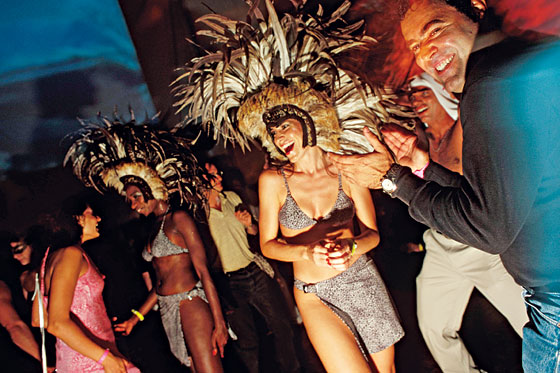

They seem almost cute now in their anachronism: self-confirmed billionaires in snug suits and tight-faced dowagers, gold-digging boys and girls on the make, supermodels and grasping politicians—all with tremendous infrastructures, traveling cities of PR people and advisers, packing into SUVs and heading east to the Hamptons, hedge-funders to the hedgerows, reveling in it, wielding their chunky cell phones like newfound ingots. No wonder we had a ball covering them!

Yet New York was a frenetic cultural enclave so complete that it seemed impossible or insane to leave it. It was so entertaining! Of course—like Fitzgerald’s New York—as a city we were a great success. Our martinet mayor had Savonarola’s license to do what he liked—but his own domestic crises as well. Money was everywhere. The New York Observer, where I worked, had an almost pornographic response when we began running the prices and specs of residential real-estate transactions every week. “I looooove it!” people kept saying. Candace Bushnell’s “Sex and the City” columns ran barefoot through the same territory and the more cancellations we got for her column the more the paper knew we had hit the jackpot.

New York in the nineties was an immovable feast. Nobody left. The city was self-confirmed, the capitalist capital of the world, bigger than Paris, beating London at its own game, Beijing who? Francis Fukuyama had shown up a few years earlier with his nutty one-liner about the End of History. Do you remember that? The gist of the theory was that Western democracy had triumphed and we were entering into some period of tremendous global dominance. They had had daffy ideas in the twenties also—mentalists and big-tent evangelists and flagpole sitters—and one of the prevalent mysticisms of the nineties was Fukuyama’s delightful assertion, a thesis so palpably incorrect that it begged to be confirmed as you would clap your hands for Tinker Bell.

Yet there was something entrancing about the End of History. You knew viscerally something was going to give. Things were cozy, quiet, luxe—and slightly fetid. It was impossible not to know.

New York had temporarily stopped, basking in itself, freeze-drying time. Irony was the voice of the city—a voice easily assigned to a town without heroes—smartness without wisdom. Seinfeld’s epic whine was our “Leaves of Grass.” Sincerity, purpose, emotion were déclassé. Incomes and real-estate prices climbed ceaselessly and so did exhibitionism, steeped in wealth, full of avarice without apology. Needless to say, it was also somewhat of a gas.

Of course part of it was the premillennial intake of breath. It caused a certain amount of anxiety, the shift from MCM to MM. And part of it was the Lamest Generation.

When the baby-boomers finally took the helm, what did they accomplish? Well, they could write a good joke. Or, in the case of our brilliant but priapic first baby-boomer president, could make one; how that happened none of us will ever know. John F. Kennedy called his presidency a long twilight struggle against our adversaries; Bill Clinton envied him his foreign crises—the only long twilight struggle he had was with Newt Gingrich. When George W. Bush was elected president, it seemed the greatest Age of Irony gag of them all—the spoiled, best-educated baby-boomers had elected our own Harding.

One afternoon, in the summer after George W. Bush’s inauguration, a few of us were sitting in my little office at the Observer with another editor making up the usual front page and we stopped cold. There was no news left. The era had run cold. How could that be? There were the usual socialite gags and billionaires buying big apartments, there was Harvey Weinstein and Martha Stewart and the sporadic rages of the late days of the Giuliani mayoralty—Rudy was just angry all the time.

We stared at one another. The era had just played itself out. It seemed as though time had stopped cold. That was impossible, of course. Except it wasn’t impossible. History was about to turn. You could almost hear the tire screech.

Here’s what we put on the front page of the paper:

“Well, this fall already feels like a bracing cold shower. Rudy Giuliani isn’t going to take care of us anymore; fashions have turned dark, bohemian, ugly; last year’s toys seem malevolent (SUVs) … The New York Post, often the guilty dessert of many a Manhattan sophisticate, has developed the loud, hacking cough of a barroom smoker. Silicon Alley is a punch line; Hillary and Bill have moved in like obstreperous big-eating out-of-town guests; those saucy, hard-core Bush Girls are in ascendance, while the Gore Girls’ dad stumbles darkly around the country, looking like Raymond Burr with beard, plummy oratory and ballooning beer gut. And if there’s a New Yorker who feels a drop of resonance with the man in the White House, we haven’t met him or her.”

The date on the paper was September 10, 2001.

I’ll tell you quickly what happened to our newspaper on September 11. There’s not a person reading this who doesn’t have his or her own story. But the Observer was a sensibility newspaper, and when history changes, so does sensibility, right away.

That morning, the conductor on my train from Westchester told us he could not pull into Grand Central Terminal. There had been a federal emergency. I got off in the Bronx and looked south. There was a little finger of smoke in the air to the south. When I got to the Observer townhouse on 64th Street the reporters were dazed, adversaries were hugging, and the toughest guy in the newsroom was bent over his desk sobbing—he had received an early report of a missing friend.

It was a Tuesday and our top story was the mayoral primary, our cover illustration was to be Michael Jackson’s birthday party. I called the artist Drew Friedman, and he faxed in a drawing of the Statue of Liberty shrouded in smoke, which we hand-tinted in the production department. We wrote this headline: SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 INFAMY: ASSAULT, COLLAPSE AT TWIN TOWERS; CITY GIRDS. The insouciance that had been the Observer’s attitude was put in cold storage. Our little insular life had been blown open.

History hadn’t ended—as a matter of fact, prehistory had just begun. New York as we knew it had changed immediately that morning in many terrible ways but one thing that changed right away was its state of mind.

Nothing that September 11, 2001, brought to the city can be called unambiguously good. Anyone who can recall the black nightscape of downtown or the sight of the 69th Regiment Armory looking like a Civil War infirmary, papered and covered with handbills searching for missing persons, or the caked human moondust at ground zero, or the acrid smell in the air in the days afterward, no one can call any of it good. We may all have the memory of friends who protected us, put us up for the night, of camaraderie and warmth and even love among New Yorkers that will never come again. But not one among us can call it good. Yet New York is a more permeable and informed city than it was. It is part of the globe as it was not. New Yorkers are part of the world. Irony isn’t dead. Americans like us better and we have come to accept some of them. The city is now pointed forward into the 21st century, as it was once wrapped lingeringly around the twentieth century. It is less an enclave of sensibility than a purveyor of intelligence.

These are neither good things nor bad but they have happened. They break the heart but quicken the pulse. New York is still the city of the century, the new one.

Peter Kaplan, editorial director of the Fairchild Fashion Group, edited the New York Observer for fifteen years.

Venus and Serena Williams and their former coach, Rick Macci, had got into a playful spat over $35 he owed one of the sisters.

Bob Guccione Jr. was flying the Rev. Michael Holleran, of St. Joseph’s Church in the Village, to Italy to preside over his September 22 wedding.

The Gracie Mansion gallery in Chelsea was opening a show inspired by the transsexual Amanda Lear.

Matthew Broderick and Sarah Jessica Parker had bought a five-bedroom Victorian fixer-upper in Bridgehampton for just under $2 million.

Several record labels were angry at MTV for charging them to get their artists on the annual Video Music Awards show. (Jennifer Lopez’s appearance had cost Sony $250,000.)

Busta Rhymes had been spotted taking his wife and two kids on a three-hour tour of the Museum of Natural History.

Robin Cook had asked restaurateur Nello Balan to proofread the Italian translation of his latest novel, Shock.

Joan Jett was about to walk the runway for Cynthia Steffe, uncharacteristically clad in skirts and frilly blouses.

Mariah Carey’s forthcoming album, Glitter, and her film of the same title, were rumored to be terrible.