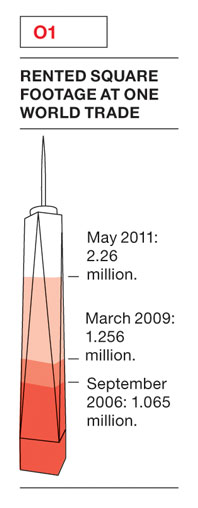

The building rising on ground zero, once known as the Freedom Tower, was one of the most difficult sells in history. Beginning in 2008, there had been some initial talks with potential tenants—Merrill Lynch’s then-CEO John Thain and JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon each kicked the tires—but the financial crisis quickly derailed any deal. “Downtown was a pit,” remembered Port Authority executive director Chris Ward. One morning in August 2010, Ward, who’d been in the job for two years and had made it his goal to get the tower built, escorted Condé Nast chairman Si Newhouse and his nephew Steven, the company’s heir apparent, up to the raw 30th floor. Si quietly took in the 360-degree panorama. “He didn’t talk—he holds his cards close,” Ward said. More than any other aspect of the sixteen-acre complex, the 2.6 million–square–foot Trade Center [O1] had become the most visible symbol of ground zero’s redevelopment. Born out of the emotional aftermath of the World Trade Center’s destruction, the 102-story Freedom Tower was an idea that many dismissed from the get-go as a hubristic folly. There seemed to be little commercial logic to it: Who would want to work on the top floor of a target? Everything about the tower—its crass 1,776-foot pinnacle, the multiple ground-breaking ceremonies, and, most visibly, its name—resulted in a skyscraper that seemed more like a vertical memorial than anything resembling a commercial-office project. And, unlike Michael Arad’s actual memorial, the Freedom Tower was expected to make money.

Under Larry Silverstein, the leaseholder and developer, the site sat unbuilt for years, as his executives haggled with government officials over financing and control. In the real-estate business, fear is never a good selling proposition. At the site, the tragic legacy of that terrible day was proving impossible to hide: In 2005, the entire design had to be revamped after Police Commissioner Ray Kelly publicly complained that the tower’s location abutting West Street rendered it vulnerable to a truck-bomb attack. “If someone decides to load up their panel truck with a bomb and drive down West Street, you’d be between the Freedom Tower and Goldman Sachs,” one executive involved in the talks at the time told me. “You’d have a terrible thing happen.”

Silverstein quickly commissioned his architect, David Childs, to draw up a new design that countered the bomb threat. The updated plan perched the tower atop a 185-foot concrete pedestal with steel columns weighing 70 tons. It solved the blast issue but left many complaining that the building looked like a fortified bunker. Childs took the criticism hard. “There’s nothing wrong with a solid building,” he told me. “You go to Florence, or the Federal Reserve, or our museums—they’re all solid.”

In 2008, when Ward took over, the site was still a teeming construction pit. Ward also knew he needed to untangle the building from the conflicted post-9/11 politics. This meant stripping the tower of its patriotic mission and recasting it, to the greatest extent possible, as a conventional skyscraper. He also knew the Port Authority needed to partner with an established developer. In July 2010, the Authority selected the Durst Organization to lease and manage the building. “We turned it into something the real-estate industry understands,” Ward said.

By then, Ward had also jettisoned the Freedom Tower name, changing it to One World Trade Center. He made the decision after the Port Authority commissioned market surveys that demonstrated what almost everyone already knew: A building called the Freedom Tower was a visceral reminder of 9/11. According to one executive involved, a respondent to the survey told the Port Authority that “we applaud the overt act of defiance aimed at the terrorists, but there are lots of employees who don’t want to make their lives part of this daily struggle.”

The move infuriated one of the building’s biggest backers: former governor George Pataki. Where Rudy Giuliani sought to be the hero of 9/11, Pataki wanted to be the hero of ground zero’s rebirth—it was an integral part of his ambition to be president. In one meeting, he had called rebuilding “a patriotic duty.”

Around the time the Port Authority gained control of the building in 2006, Condé Nast executives began to discuss the future of their magazine empire. Condé’s lease at 4 Times Square was set to expire in 2019, and its broker, Mary Ann Tighe of CB Richard Ellis, worked with Newhouse to develop options. Newhouse called the real-estate effort “Project Hedgehog,” after one of his favorite Isaiah Berlin essays, “The Hedgehog and the Fox.”

For its role in remaking Times Square, Condé Nast had been rewarded with tax breaks, giving it an annual rent of about $40 per square foot. In looking for a similar deal, Newhouse’s team even pushed into outer boroughs, touring Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn, addresses in Long Island City, and locations along the Jersey City waterfront. One morning in the fall of 2009, Ward got the call he’d been waiting for: Si Newhouse told him he wanted to tour ground zero. Months later, outlines of a deal emerged. In April 2010, Tighe sent Ward a formal bid, attaching a 1998 Vogue article that included photographs of models standing on the steel girders of the then-unfinished 4 Times Square. Condé and the Port Authority quickly agreed on price, but the final deal was far from done. That would take a series of all-day negotiations in a conference room in the Durst-owned Bank of America tower, stretching over ten months. “There were a lot of conversations about, How quickly can Anna Wintour get the dresses up so she can approve them?” one executive close to the talks told me. Condé executives also got assurances that their fleet of black Lincolns would be able to whisk through the building’s fortresslike security-screening complex. Finally, this past May, Newhouse ascended the construction elevators to the Trade Center’s thirty-fourth floor to sign the lease—he had come to see the deal as a part of his legacy. At Condé, there were rumors that magazines were fighting to occupy the lowest floors. But Condé’s executives expected this. Said the company’s COO, John Bellando: “To deny it would be on folks’ minds would be naïve.”