The way it worked was one of the Times editors would come over to your desk with eight or ten new leads. If you drew a firefighter, you’d just go down there. Otherwise you’d call and say your business and listen. Sometimes the voice on the other end was already talked out; sometimes it seemed like you were the first person they’d talked to since. The former was okay. The latter was a mess.

Janny Scott from Metro got the project started. For the first batch, she enlisted her colleagues on the desk, Diane Cardwell, Glenn Collins, Winnie Hu, Andrew Jacobs, Lynda Richardson, and Joyce Wadler. This was three days after the attacks, when the dead at the Trade Center officially numbered 124. The “Portraits of Grief” weren’t called that yet, but they addressed a city deep in stage one. They told of an investment banker, a pastry chef, a former Marine, and others still half-expected to come bursting through the door singed and soaking at 3 a.m. with an increasingly improbable tale of escape. Obituaries these were most pointedly not.

One of those first Portraits set the bar for the rest. In about 150 words, the writer introduced one Gary J. Frank as a cast-against-type computer programmer playing pool in smoky barrooms, referenced the custody arrangement of his 12-year-old daughter, and then dropped the kicker: “This would have been their weekend.” The original Metro group soon became the Glengarry Glen Ross of sorrow, always closing, adding staffers from other desks to keep pace with the grief. For the New York Times, this was a significant departure. At a time when the Washington bureau was covering a massive government overhaul, Investigations was tracking the attackers, and Foreign was staffing up for invasions of wherever, the paper devoted more than 140 reporters, plus editors, researchers, and support staff, to chronicle how people were feeling.

In the end, we filed more than 2,400 Portraits. I remember disconnected details, because details were what we pushed for: an airline employee with a weak spot for Barry Manilow, a salesman with a taste for Grey Goose martinis. But by October, the details were starting to fail us. For example, The Simpsons: After a while it got to be noticed and then it got to be funny and then it got to be embarrassing and then it got to be a problem that a great many if not most of the men between the ages of 20 and 40 were described as admirers of the show. In 150 words, it’s a telling detail. In 150 sets of 150 words, it’s farcical. I never heard anybody say, “No more Simpsons,” but somehow nobody had to.

By prize season the job was almost done, and we each got a coffee-table book. I took mine around for autographs. Somebody wrote, “Best wishes”; somebody else wrote, “With love.” Mostly people just wrote their names. I didn’t know why I was collecting signatures, so I stopped after a couple pages. I know now. Most of the people I worked with on “Portraits” are out of my life. Some I miss and others I don’t. But I have a book that says we were there and that happened and then we got up and did this. Michael Brick, a former New York Times reporter, was part of the team that wrote the paper’s “Portraits of Grief.”

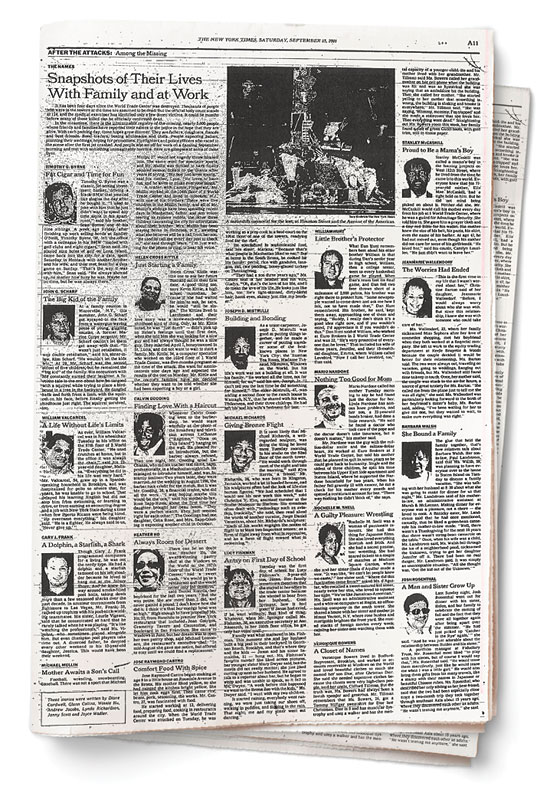

Selections from the Times’ first twentymemorial profiles, published on September 15.