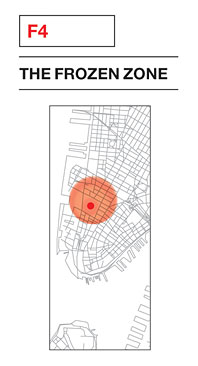

In 2001, I lived down by the frozen zone. From our rooftop in Tribeca, we’d watched the Towers collapse with “malign majesty,” as Ian McEwan later wrote. Our building shook; a bright toxic cloud rushed up Church Street and slipped under my windows and into my loft. And then days later, the fence went up—12,000 feet of chain-link cut our neighborhood in half. From Chambers Street toward Rector Street, and from Broadway to the West Side Highway, was the frozen zone [F4]. No one but officials passed—soldiers with automatic weapons made sure of that. But even north of the zone, life as we’d known it had ceased. Neither cell phones nor land lines worked. P.S. 234, like Stuyvesant High School, like the many neighborhood preschools, once anchors of the community, had been evacuated. The long black Town Cars that regularly idled in front of destination restaurants like Bouley and City Hall were gone. “I’m going broke day by day,” Drew Nieporent, owner of Nobu and Tribeca Grill, told me at the time.

But for those of us who stayed, there was a surprise in store. The weeks after 9/11 were, strangely, a kind of joyful time. Life had pretty much ground to a halt—the very notion of a “career” seemed slightly funny then. And yet, the tragedy offered something to replace all that. Strangers embraced one another. People donated clothes, which piled up on a street corner, since no one was there to collect them. Even Eden Day Spa on Broadway wanted to help, offering free massages to rescue workers.

The silent Korean cashier at Morgan’s deli on Hudson Street, usually so intent on counting out pennies and dimes, cried—and gave away his melting ice cream. “Maybe facing death together is a bonding experience,” said Lisa Schiller, a longtime Tribeca resident, who wrapped her arms around him. An aging punk-rocker named George Tabb hugged his postal worker when the mail delivery started up within a few days after the attack. “Tribeca is a cross between a war zone and Woodstock,” someone said.

Rocco Cadolini, owner of Roc restaurant, which had opened in 2000, welcomed the neighborhood to a free dinner. “Rather than sit home and do nothing,” he said, “I cooked.” I spent a couple of evenings at Roc, pulling up a chair at one of the communal tables, listening to the awful stories people told each other—someone was sure she’d seen a hand-holding couple step off a top floor of the World Trade Center and into space—and taking comfort in the company of strangers.

And then it was over. The smoke lingered in the air, but the fence went, and the stock market eventually rebounded, tugging real-estate prices along with it. Within a year or two, the old normal was back. New people flooded into Tribeca. Always well-off, the neighborhood was on its way to becoming the richest Zip Code in the country, richer than Beverly Hills. “New people think different,” said Cadolini. “The new people, they don’t care about the neighborhood in the same way. They’re friendly, of course, but they’re in a hurry—there are only so many hours in a day.”

“That feeling was illusory,” recalled Alexander Gorlin, who along with his wife had been taken in by strangers as he fled uptown on September 11. Gorlin, an architect, now divorced and living outside Tribeca, said, “It vanished.”

From the archives

• Tribeca: The View Down Here (New York Magazine, March 11, 2002)

• The Talking Cure (New York Magazine, October 1, 2001)

• Down by the Frozen Zone (New York Magazine, October 1, 2001)