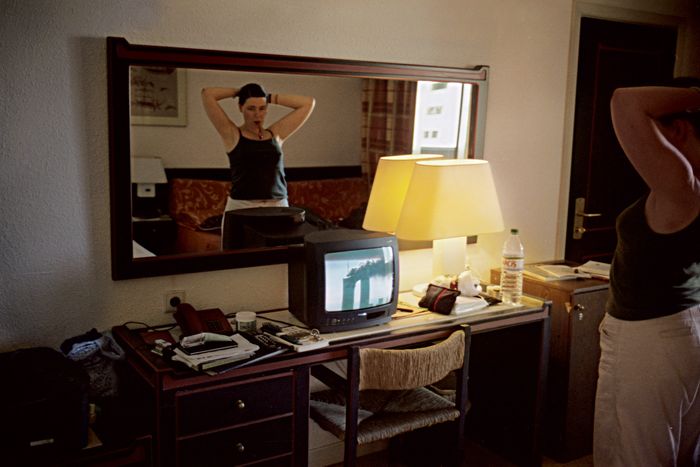

On September 11, a friend called to tell me to turn on the TV. I did, just as the second plane hit. By that afternoon, I was holed up in the West Village, desperate to escape the traumatizing loop of footage. Better to drink with friends instead.

But of course, I couldn’t stop watching. Because a decade ago, television was not just one way to follow the crisis; it was the only way. In 2001, online newspapers were rudimentary, with no blogs, video, or comments; most people had dial-up. There were cell phones, but texting wasn’t widespread, and cameraphones were rare. Facebook launched in 2004, and Twitter in 2006. While you could e-mail or instant-message people you knew well, only technically adroit geeks could speak easily to a wider audience. We needed the professionals to fill us in: Peter Jennings, Diane Sawyer, Aaron Brown, Charles Gibson, Katie Couric, Matt Lauer, Tom Brokaw, Paula Zahn, not to mention Ashleigh Banfield, who ran 40 blocks down Sixth Avenue, reported the falling of the first Tower from her cell phone, then got caught in the mêlée when the second Tower fell.

Luckily, they came through. Because in those first hours, TV news—however briefly—became news again. The anchors reacted to events as they happened, with recognizable emotions, yet keeping panic in check. Gibson warned several times: “We are dealing purely in the realm of speculation here.” Field reporters were no longer voyeurs; they were downtown themselves, struggling to find context in the chaos. Peter Jennings was on the air for seventeen hours straight, his deep voice and intelligent notes of caution far more comforting than the clichés of President Bush. Twelve hours in, Jennings took a break to call his children, then offered personal advice, acknowledging the unusual break in rhetoric. “If you’re a parent, you’ve got a kid in some other part of the country, call them up. Exchange observations.”

Much of the information from those first hours turned out to be useless, like instructions about where to give blood. There were rumors about hijacked planes and bomb threats that didn’t exist, as producers struggled to gauge what was real. Reporters held up missing posters to the cameras, encouraging strangers to read descriptions of loved ones who would never be found.

And it wasn’t long—a day or two—before the scrim rose back up, the stirring theme songs and patriotic slogans like “America Under Attack” that would continue into the Iraq War. TV news became what it had always been—ideology and entertainment—but with even greater intensity, and more open cynicism, with the rise of Fox News. These days, we all ride the cycle of immediacy, from Anderson Cooper’s reports during Hurricane Katrina, to the tweets from Haiti, to the Facebook rebels in Egypt and the comments appended to every article, daggers stabbing through news copy that was once untouchable, authoritative. Some of this new style is radical and democratic, an improvement over the phony “truth” of the past; just as often it is merely exploitative, a performance of feeling as fake as any Sam the Eagle gravitas ever was.

It wasn’t until 2005 that YouTube was created, lending us access to what is now a fetishized archive of 9/11 footage, available any hour, spattered with conspiracy theories. “Oh, this is terrifying, awful,” says Gibson, witnessing the second plane hitting. “To watch powerless, it’s a horror,” responds Sawyer. My heart beat faster as I watched, no matter how I tried to keep myself at a distance, even a decade later. But I also found that it was possible to feel a kind of perverse nostalgia, a tenderness for TV news trying its best.

Mid-September 2001 (Terror Attacks): TV, 90 percent; internet, 5 percent.

March 2003 (Iraq War): TV, 89 percent; internet, 11 percent.

Early September 2005 (Hurricane Katrina): TV, 89 percent; internet, 21 percent.

January 14–17, 2010 (Haiti earthquake): TV, 69 percent; internet, 31 percent.

May 5–8, 2011 (Killing of bin Laden): TV, 74 percent; internet, 39 percent.

Source: Pew Research Center, July 2011 The Anchor

“My God! The southern tower, ten o’clock Eastern time this morning, just collapsing on itself. This is a place where thousands of people worked. We have no idea what caused this.”