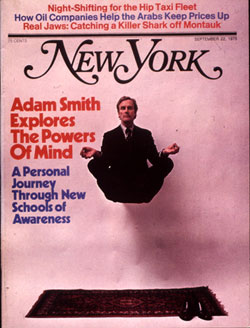

From the September 22, 1975 issue of New York Magazine.

It has been a year since I drove a cab, but the old garage still looks the same. The generator is still clanging in the corner. The crashed cars are still in the shop. The weirdos are still sweeping the cigarette butts of the cement floor. The friendly old “YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE for all front-end accidents” is as comforting as ever. Danny the dispatcher still hasn’t lost any weight. And all the working stiffs are still standing around, grimy and gummy, sweating and regretting, waiting for a cab at shape-up.

Shape-up time at Dover Taxi Garage #2 still happens every afternoon, rain or shine, winter or summer, from two to six. That’s when the night-line drivers stumble into the red-brick garage on Hudson Street in Greenwich Village and wait for the day liners, old-timers with backsides contoured to the crease in the seat of a Checker cab, to bring in the taxis. The day guys are supposed to have the cabs in by four, but if the streets are hopping they cheat a little bit, maybe by two hours. That gives the night liners plenty of time to stand around in the puddles on the floor, inhale the carbon monoxide, and listen to the cab stories.

Cab stories are tales of survived disasters. They are the major source of conversation during shape-up. The flat-tire-with-no-spare-on-Eighth-Avenue-and-135th-Street is a good cab story. The no-brakes-on-the-park-transverse-at-50-miles-an-hour is a good cab story. The stopped-for-a-red-light-with-teen-agers-crawling-on-the-windshield is not too bad. They’re all good cab stories if you live to tell about them. But a year later the cab stories at Dover sound just a little bit more foreboding, not quite so funny. Sometimes they don’t even have happy endings. A year later the mood at shape-up is just a little bit more desperate. They gray faces and burnt-out eyes look just a little bit more worried. And the most popular cab story at Dover these days is the what-the-hell-am-I-doing-here? story.

Dover has been called the “hippie garage” ever since the New York freaks who couldn’t get it together to split for the Coast decided that barreling through the boogie-woogie on the East River Drive was the closest thing to rid-ing the range. The word got around that the people at Dover weren’t as mean or stodgy as at Ann Service, so Dover became “the place” to drive. Now, most of the hippies have either ridden into the sunset or gotten hepatitis, but Dover still attracts a specialized personnel. Hanging around at shape-up today are a college professor, a couple of Ph.D. candidates, a former priest, a calligrapher, a guy who drives to pay his family’s land taxes in Vermont, a Rumanian discotheque D.J., plenty of M.A.’s, a slew of social workers, trombone players, a guy who makes 300-pound sculptures out of solid rock, the inventor of the electric harp, professional photographers, and the usual gang of starving artists, actors, and writers. It’s Hooverville, honey, and there isn’t much money around for elephant-sized sculptures, so anyone outside the military-industrial complex is likely to turn up on Dover’s night line. Especially those who believed their mother when she said to get a good education so you won’t have to shlep around in a taxicab all your life like your Uncle Moe. A college education is not required to drive for Dover—all you have to do is pass a test on which the hardest question is “Where is Yankee Stadium?”—but almost everyone on the night line has at least a B.A.

Shape-up lasts forever. The day liners trickle in, hand over their crumpled dollars, and talk about the great U-turns they made on 57th Street. There are about 50 people waiting to go out. Everyone is hoping for good car karma. It can be a real drag to wait three hours (cabs are first come, first served) and get stuck with #99 or some other dog in the Dover fleet. Over by the generator a guy with long hair who used to be the lead singer in a band called Leon and the Buicks is hollering about the state the city’s in. “The National Guard,” he says, “that’s what’s gonna happen. The National Guard is gonna be in the streets, then the screws will come down.” No one even looks up. The guy who says his family own half of Vermont is diagnosing the world situation. “Food and oil,” he says, “they’re the two trump cards in global economics today … we have the food, they have the oil, but Iran’s money is useless without food; you can’t eat money.” He is running his finger down the columns of the Wall Street Journal, explaining to a couple of chess-playing Method actors what to buy and what to sell. A lot of Dover drivers read the Wall Street Journal. The rest read the Times. Only the mechanics, who make considerably more money, read the Daily News. Leaning up against the pay telephone, a guy wearing a baseball hat and an American-flag pin is talking about the Pelagian Heresies and complaining about St. Thomas Aquinas’s bad press. His cronies are laughing as if they know what the Pelagian Heresies are. A skinny guy with glasses who has driven the past fourteen nights in a row is interviewing a chubby day liner for Think Slim, a dieters’ magazine he tried to publish in his spare time. The Rumanian discotheque D.J. is telling people how he plans to import movies of soccer games and sell them for a thousand dollars apiece. He has already counted a half-millions in profits and gotten himself set up in a Swiss villa by the time Danny calls his number and he piles into #99 to hit the streets for twelve hours.

Some of the old favorites are missing. I don’t see the guy with the ski tours. He was an actor who couldn’t pay his Lee Strasberg bills, and was always trying to sign up the drivers for fun-filled weekends in Stowe. Someone says he hasn’t seen the guy for a few months. Maybe he “liberated” himself and finally got to the mountains after all. Maybe he’s in a chalet by a brook right now waiting for the first snowfall instead of sweating and regretting at shape-up. Dover won’t miss him. Plenty of people have come to take his place.

“I don’t look like a cabdriver, do I?” Suzanne Gagne says with a hopeful smile. Not yet. Her eyes still gleam—they aren’t fried from too many confrontations with the oncoming brights on the Queensboro Bridge. Suzanne, a tall woman of 29 with patched blue jeans, is a country girl from the rural part of Connecticut. She got presents every time she graduated from something, so she has three different art degrees. When school got tiresome, she came to New York to sell her “assemblages” (“I don’t care for the word collage”) in the SoHo galleries. There weren’t many immediate takers and her rent was high, so now Suzanne drives for Dover several nights a week.

A year ago or so, any woman hanging out at shape-up was either waiting to report a driver for stealing her pocketbook, a Dover stiff’s girl friend, or some sort of crazy cabdriver groupie. In those days, the two or three women who were driving were banned from the night line, which is notably unfair because you can make a lot more money with a lot less traffic driving at night. Claire, a long-time Dover driver, challenged the rule and won; now fifteen women drive for Dover, most on the night line. There are a lot of reasons why. “I’m not pushing papers anymore,” says Sharon, a calligrapher and former social worker who drove for Dover until recently. “I can’t hack advertising.” Sharon says many more women will be driving soon because women artists need the same kind of loose schedule that has always attracted their male counterparts to cabdriving. At Dover you can show up when-ever you want and work as many days as you can stand. Besides, she says, receptionist and typist positions, the traditional women’s subsistence jobs, are drying up along with the rest of the economy. The women at Dover try not to think about the horrors of the New York Night. “You just have to be as tough as everyone else,” Sharon says. But since Suzanne started driving, and artwork that she used to do in two or three days is taking weeks. “I’m tired a lot,” she says, “but I guess I’m driving a cab because I just can’t think of anything else to do.”

Neither can Don Goodwin. Until a while ago he was president of the Mattachine Society, one of the oldest and most respected of the gay-liberationist groups. He went around the country making speeches at places like Rikers Island. But now he twirls the ends of his handlebar mustache and says, “There’s not too much money for movements, movements are gastunk.” Don sometimes daydreams in his cab. He thinks about how he used to dress windows for Ohrbach’s and how he loved that job. But this salary got too high and now he can’t get another window-dresser’s job. Don offered to take a cut in pay but “in the window-dressing business they don’t like you to get paid less than you got paid before, even if you ask for it. Isn’t that odd?” Now Don’s driving seven days a week because “after window-dressing and movements, I’m really not skilled to do anything else.”

A driver I know named David is worried. David and I used to moan cab stories to each other when I was on the night line. Now he keeps asking me when I’m coming to work. After four years of driving a cab, he can’t believe interviewing people is work. David is only a dissertation away from a Ph.D. in philosophy, which makes him intelligent enough to figure out that job openings for philosophers are zilch this year. The only position his prodigious education has been able to land him was a $25-a-night, one-night-a-week gig teaching ethics to rookie cops. David worked his way through college driving a cab. It was a good job for that, easy to arrange around things that were important. Now he has quit school in disgust and he arranges the rest of his life around cab-driving. He has been offered a job in a warehouse for which he’d make $225 a week and never have to pick up another person carrying a crowbar, but he’s not going to take it. At least when you’re zooming around the city, there’s an illusion of mobility. The turnover at the garage (Dover has over 500 employees for the 105 taxis; it hires between five and ten new people a week) makes it easy to convince yourself this is only temporary. Working in a factory is like surrender, like defeat, like death; drudging nine to five doesn’t fit in with a self-conception molded on marches to Washington. Now David’s been at Dover for the past two years and he’s beginning to think cab freedom is just another myth. “I’ll tell you when I started to get scared,” David says. “I’m driving down Flatbush and I see a lady hailing, so I did what I normally do, cut across three lanes of traffic and slam on the brakes right in front of her. I wait for her to get in, and she looks at me like I’m crazy. It was only then I realized I was driving my own car, not the cab.”

David has the Big Fear. It doesn’t take a cabdriver too long to realize that once you leave the joy of shape-up and start uptown on Hudson Street, you’re fair game. You’re at the mercy of the Fear Variables, which are (not necessarily in order): the traffic, which will be in your way; the other cabdrivers, who want to take your business; the police, who want to give you tickets; the people in your cab, lunatics who will peck you with nudges and dent you with knives; and your car, which is capable of killing you at any time. Throw in your bosses and the back inspectors and you begin to realize that a good night is not when you make a living wage. That’s a great night. A good night is when you survive to tell your stories at tomorrow’s shape-up. But all the Fear Variables are garbage compared with the Big Fear. The Big Fear is that times will get so hard that you’ll have to drive five or six nights a week instead of three. The Big Fear is that your play, the one that’s only one draft away from a possible show-case will stay in your drawer. The Big Fear is thinking about all the poor stiff civil servants who have been sorting letters at the post office every since the last Depression and all the great plays they could have produced. The Big Fear is that, after twenty years of schooling, they’ll put you on the day shift. The Big Fear is you’re becoming a cabdriver.

The typical Big Fear cabdriver is not to be confused with the archetypal Cabby. The Cabby is a genuine New York City romantic hero. He’s what every out-of-towner who’s never been to New York but has seen James Cagney movies thinks every Big Apple driver is like. A Cabby “owns his own,” which means the car he drives is his, not owned by some garage boss (58 per cent of New York’s 11,787 taxis are owned by “fleets” like Dover which employ the stiffs and the slobs of the industry; the rest are operated by “owner-drivers”). The Cabby hated Lind-say even before the snowfalls, has dreams about blowing up gypsy cabs, knows where all the hookers are (even in Brooklyn), slurps coffee and downs Danish at the Belmore Cafeteria, tells his life story to everyone who gets into the cab, and makes a ferocious amount of money. But mostly, he loves his work. There aren’t too many of them around anymore. The Dover driver just doesn’t fit the mold. He probably would have voted for Lindsay twice if he had had the chance. He doesn’t care about gypsies; if they want the Bronx, let them have it. He knows only about the hookers on Lexington Avenue. He has been to the Belmore maybe once and had a stomach ache the rest of the night. He speaks as little as possible, and barely makes enough to get by. He also hates his work.

The first fare I ever had was an old bum who threw up in the back seat. I had to drive around for hours in miserable weather with the windows open trying to get the smell out. That started my career of cabbing and crabbing. In the beginning, before I became acquainted with the Big Fear and all it attendant anxieties, the idea was to drive three days a week, write three, and party one. That began to change when I realized I was only clearing about $27 for every ten-hour shift. (A fleet driver makes from 43 per cent to 50 per cent of his meter “bookings,” depending on seniority, plus tips; please tip your cabdriver.)

There were remedies. The nine-hour shift stretches to twelve and fourteen hours. You start ignoring red lights and stop signs to get fares, risking collisions. You jump into cab lines when you think the other cabbies aren’t looking, risking a punch in the nose. You’re amazed what you’ll do for a dollar. But mostly you steal.

If you don’t look like H. R. Haldeman and take taxis often, you’ve probably been asked by a cabdriver if it’s “okay to make it for myself.” The passenger says yes, the driver sets a fee, doesn’t turn on the meter, gets the whole fare for himself, and that’s stealing. Stealing ups your Fear Variables immeasurably. You imagine hack inspectors and company-hired “rats” all around you. Every Chevy with black-wall tires becomes terror on wheels. The fine for being caught is $25, but that’s nothing—most likely you will be fired from your garage and no one will hire you except those places in Brooklyn with cars that have fenders held on with hangers and brake pedals that flap. But you know that if you can steal, say $12 a night, you’ll only have to drive three nights this week instead of four and maybe you’ll be able to get some writing done.

All of this is bad for your writer’s distance and your actor’s instrument, to say nothing of your self-respect; but nothing is as bad as premonitions. Sometimes a driver would not show up at Dover shape-up for a couple of days and when he came in he’s say, “I didn’t drive because I had a premonition.” A premonition is knowing the Manhattan Bride is going to fall in the next time you drive over it and thinking about whether it would be better to hit the river with the windows rolled up or down. On a job where there are so many different ways to die, pre-monitions are not to be discounted. Of course, a smile would lighten everything, but since the installation of the partition that’s supposed to protect you and your money from a nuclear attack, cabdriving has become a morose job. The partition locks you in the front seat with all the Fears. You know the only reason the thing is there is be-cause you have to be suspicious of everyone on the other side of it. It also makes it hard to hear what people are saying to you, so it cuts down on the wisecracking. The partition killed the lippy cabby. Of course, you can always talk to yourself, and most Dover drivers do.

When I first started driving, cabbies who wanted to put a little kink into their evening would line up at a juice bar where they gave Seconals along with the Tropicana. The hope was that some Queens cutie would be just messed up enough to make “the trade.” But the girl usually wound up passing out somewhere around Francis Lewis Boulevard, and the driver would have to wake her parents up to get the fare. Right now the hot line is at the Eagle’s Nest underneath the West Side Highway. The Nest and other nearby bars like Spike’s and the Nine Plus Club are the hub of New York’s flourishing leather scene. On a good night, dozens of men dressed from hat to boots in black leather and rivets walk up and down the two-block strip and come tumbling out of the “Tunnels,” holes in the highway embankment, with their belts off. Cabdrivers with M.A.’s in history will note a resemblance to the Weimar Republic, another well-known depression society.

Dover drivers meet in the Eagle’s Nest line after 2 a.m. almost every night. The Nest gives free coffee, and many of the leather boys live on the Upper East Side or in Jersey, both good fares, so why not? After the South Bronx, this stuff seems tame. Besides, it’s fun to meet the other stiffs. Who else can you explain the insanity of the past nine hours of your life to? It cuts away some of the layers of alienation that have been accumulating all night. Big Fear cabdrivers try to treat each other tenderly. It’s a rare moment of cab compassion when you’re deadheading it back from Avenue R and you hear someone from the garage shouting “DO-ver! Do-ver!” as he limps out to Coney Island. It’s nice, because you know he’s probably just another out-of-work actor-writer stiff like you, lost in the dregs.

So it figures that there is a strong feeling of “solidarity forever” in the air at Dover. The Taxi Rank and File Coalition, the “alternative” cab union in town (alternative to Harry Van Arsdale’s all-powerful and generally despised Local 3036), has been trying to organize the Dover drivers. Ever since I started cabbing, Rank and Filers have been snickered at by most drivers as Commies, crazy radical hippies, and worse. A lot of this was brought on by the Rank and File people themselves, who used to go around accusing old-timers of being part of the capitalist plot to starve babies in Vietnam. This type of talk does not go over too big at the Belmore. Now Rank and File has toned down its shrill and is talking about more tangible things like the plight of drivers in the face of the coming depression, and members are picking up some scattered support in the industry. Dover, naturally, is their stronghold; Van Arsdale’s people have just about given the garage up for lost. Suzanne Gagnes wears a Rank and File button. Suzanne says, “It’s not that I’m a left-wing radical or anything. I just think it’s good that we stick together in a situation like this.”

Last winter a bitter dispute arose over an incident in which a Dover driver returned a lost camera and the garage allegedly pocketed the forthcoming reward money. The Rank and File leaders put pressure on the company to admit thievery. The garage replied by firing the shop chairman, Tom Robbins, and threatening the rest of the committee. Tempers grew very hot; petitions to “Save the Dover 6” were circulated. Robbins appealed to the National Labor Relations Board , but no action was taken. There was much talk of a general strike, but Rank and File, surveying the strength of their hardcore membership, decided against it. Now they have another NLRB suit against Dover and the Van Arsdale union for what they claim is a blacklist against Robbins, who has been turned down in attempts to get a job at twenty different garages in the city.

Gerry Cunningham, who is the boss at Dover, says Rank and File doesn’t bother him. “You’d figure there would be a lot of those types here, the way I see it. Big unions represent the median sort of guy, so you’d figure that with the general type of driver we have here, there would be a lot of Rank and File. Look, though, I’m not particularly interested in someone’s religion as long as he produces a day’s work. If the drivers feel a little togetherness, that’s fine with me.” Gerry, a well-groomed guy with a big Irish face, is sifting through a pile of accident reports and insurance claims in his trailer-office facing Hudson Street. It seems like all cab offices are in trailers or tempo-rary buildings; it’s a transient business. This is the first time, after a year of driving for Dover, that I’ve ever seen Gerry Cunningham. I used to cash the checks too fast to notice that he signed them. Cunningham smiles when he hears the term “hippie garage.” “Oh, I don’t mind that,” he says. “We have very conscientious drivers here. We have more college graduates here than any other group … I assume they’re having trouble finding other work.” Gerry is used to all the actors and writers pushing around Dover hacks and thinks some of them make good drives and some don’t. “But I’ll tell you,” he says, “of all the actors we’ve ever had driving here, I really can’t think of one who ever made it.”

Gerry Cunningham thinks that’s kind of sad, but right now he’s got his own problems. “Owning taxis used to be a great business,” he says, “but now we’re getting devoured. In January of 1973 I was paying 31 cents for gas, now I’m paying 60. I’m barely breaking even here. It cost me $12.50 just to keep a car in the streets for 24 hours. Gas is costing almost as much as it costs to pay the drivers.”

It’s no secret that fleets like Dover are in trouble. They were the ones who pressed for the 17.5 per cent fare rise and still say it’s not enough to offset spiraling gas costs, car depreciation, and corporate taxes. Some big fleets like Scull’s Angels and Ike-Stan, which employ hundreds of drivers, are selling out; many more are expected to follow. There is a lot of pressure for change. The New York Times has run editorials advocating a major reshaping of the industry, possibly with all cabs being individually owned.

But Gerry Cunningham, who is the president of the M.T.B.O.T (The Metropolitan Taxicab Board of Trade, which represents the fleets), isn’t planning on packing it in. He thinks he can survive if the fleets institute “leas-ing,” a practice the gypsy cab companies have always used. Leasing means, according to Cunningham, “I keep all my cars and lease them out to drivers for about $200 a week. That way only one man drives the car instead of the six or seven who are driving it now, the car lasts much longer, and you cut away a good deal of the maintenance and things like that.” Cunningham thinks leasing is the only way the fleets can make it right now. “It’s got to be,” he says, “because for the first time in my life, it’s hard to come to work.”

Leasing could really shake up the cabbing and crabbing, although Cunningham claims it won’t affect the “part-time actor and writer types” and the guys “who think of cabdriving as a stop along the way.” These people, he says, can always “sublet” taxis if they can’t come up with the $200.

A couple of Dover drivers who are really actors and musicians are talking about leasing while waiting in line at the La Guardia lot.

“What a drag leasing would be,” says an actor who has only $12 on the meter after four hours out of the garage. “If that happens, I don’t know, I’ll try to get a waiter’s job, I guess.”

“Yeah man, that’ll be a bitch all right,” says the musician. “I hate this goddamn job. Hey, I’d rather be blowing my horn, but right now I’m making a living in this cab. I won’t dig it if they take it away from me. Damn, if the city had any jobs I’d be taking the civil-service test.”