The wave is up, then the wave crashes—”

Slam!

It’s Jerry Brown, whacking his hand on a long wooden table for emphasis. The attorney general for the State of California, son of two-time governor Edmund “Pat” Brown Sr. (1959 to 1967), himself a two-time governor (1975 to 1983), three-time presidential candidate, two-time Senate candidate, and former mayor of Oakland, is talking about the economic wave California rode from riches to rags.

Slam!

It’s 9 a.m., and the sound echoes in this empty storefront loft tucked away in a gentrified warehouse district of Oakland, a campaign headquarters that also serves as a shrine to Brown’s past glories, full of faded magazine covers and election posters. With his shaved head and beakish nose, Brown, 72, has the look of an old buzzard, but one bristling with unpredictable energy. Whereas every other politician mentions the fact that California is the eighth-largest economy in the world by GDP, the man who would vanquish billionaire former eBay CEO Meg Whitman in the race for governor seems to back into the fact like he’s working it out on the fly. At first he tells me California is the second-largest economy, after China.

“What does China show, $1.3 trillion quarterly? Let’s see … multiply that by four … about $5.2 trillion. We’re—no, no we’re not. Shit. We’re $1.8 trillion. There are only seven countries bigger than that! Only seven. And we’re only 38 million people.”

From here, Brown proceeds to explain the present state of California, and the state of the union, in its entirety, in one tumbling monologue, like Jack Kerouac on CNN:

It’s a very productive state—and new things! Medical advances, iPhones. Different, um, stuff. It’s the software—so! Biotech, it’s here. Are there problems? Yes, there are problems. But are there problems in America, are there problems in Afghanistan, are there problems everywhere? There are problems. And maybe there are problems in China; we just haven’t seen them yet.

So! [Slam!]

Difficult to deal with. Not as easy as it was when you’re tearing down orange trees and lemon groves and putting up savings-and-loans associations [slam!] and schools [slam!] and moderately priced houses [slam!]. That’s true. When you just push into the virgin land, it’s like the settling of the West [slam!], it just continued [slam!]. That’s not quite the way it is now. It’s a more tight system [slam!]. We’re caught in [slam!] 38 million people with [slam!] 30 million vehicles, with so much [slam!] pollutants spewing out, with so much oil coming in to feed it and a housing boom and there we are … We’re riding this wave. But we’re not in charge of the wave, and even Obama is not in charge of the wave, and even the Federal Reserve, Bernanke. Does he know what he—he studied the Depression! We have Krugman, says more stimulus, and we have Republicans, say, no, austerity is the path [slam!], just tuck it, suck it in, and go forward.

So we have a complete disagreement on how to proceed. But! In the middle of all that, $1.8 trillion. And it’s going up this year. We have a management challenge. We have a very polarized Legislature, just like in Washington. And the Republicans say, Yes’m, and the Democrats say, No’m, and they just sit there and they talk and they talk, the governor just talks and talks, and nothing happens. Okay. I got that. But, it’s still a rich state. And I really believe that at this stage in my life, I’m the man to fix it. I know it as well as any human being in California. And I’m in a position to do something. A dead-heat race! And if people want me to use my skills, my energy, my imagination, my integrity, I’ll do it.

If they don’t, it’s fine with me.

Jerry Brown wasn’t the only one. Everywhere I traveled in California, people talked—and talked and talked—about the sense that something is ending.

On the surface, the reason is plain: The State of California, as a fiscal entity, is in ruins. Crushed by the housing collapse of 2008, California is essentially bankrupt, with a perilous $88 billion in debt. With no money in the coffers, the state has offered IOUs to its lenders. Unemployment is at 12.4 percent, third highest in the nation. Once the state with the most envied education system in the U.S., California is now tied for last in national reading scores—and ahead of only Mississippi, Alabama, and Washington, D.C., in math. The road to Sacramento, among the nicer ones in the state’s once-glorious highway network, is a patchwork of crumbling black and gray asphalt lined with billboards for Indian casinos.

But people, as concerned as they were about the end of the state as a functioning fiscal entity, were even more concerned about the end of something else: the story of California. The fairy tale. The Dream. And this idea, that the whole preposterous opera was coming to a close, was indescribably horrible and beautiful at the same time. “The California narrative has come to a kind of halt,” says Kevin Starr, a history professor at USC who has written a seven-volume history of the state. All those thousands of stories, told by Steinbecks and Didions and newspaper barons and politicians, and millions of others, written in the sand and dirt and orange groves by dust bowlers and migrants and former shtetl dwellers out to make a million dollars where no one cared about their religion, were really one story, the only thing that everyone had a piece of. And now everyone I met out there seemed to think this story was coming to an end, unless someone could save it. Maybe the state would get saved, too.

Of course, the Dream was part of the problem. The mythologies of gold rushes and personal reinvention and endless pleasure under the palm trees have been a powerful magnet and engine of California’s growth—but they’ve also created a kind of Ponzi scheme, allowing California to believe that it could continually expand its social net for 50 years while simultaneously cutting its own taxes. But if the California Dream is the problem, nobody would admit it. Out there, they talk like it’s a civil right. If you eliminate the Dream, what’s left? Illinois with some nice beaches.

No self-respecting Californian would want to live in such a place. And they don’t! Ominously, more people are now leaving the state than coming in, a reverse gold rush. Is that why this election is so bizarre? An antique barnstormer like Jerry Brown—Governor Moonbeam—going for the glory one last time, running against a power-suited billionaire businesswoman in pearls—from out East, no less—to replace a down-on-his-luck action hero? And the power-suited high-tech tycoon wasn’t even the only power-suited high-tech tycoon promising a better day. The whole state was a little dizzy. And all the more so these days because in California, you can get pot pretty much anywhere.

A warehouse in San Diego, a tinted-window company in an office park lined with palm trees. Parking lots full of cars gleaming in the 95-degree heat.

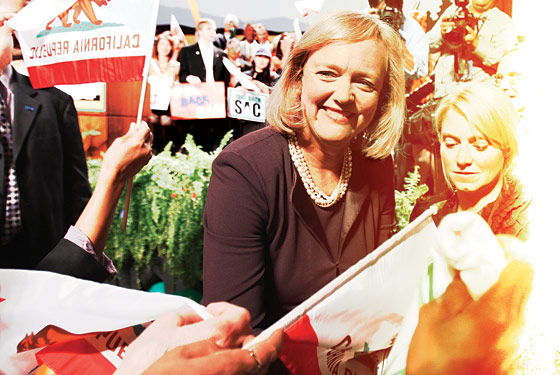

Meg Whitman, the Republican candidate for governor, former chief executive of eBay, author of The Power of Many: Values for Success in Business and in Life, is about to appear on a stage. Big industrial fans are being set up to cool a group of factory workers in identical sky-blue T-shirts, a carefully selected ethnic panorama sitting on a riser, over which a big glossy sign declares, JOBS ARE ON THE WAY!

Suddenly, Whitman’s theme song blasts over the PA, signaling her imminent arrival. It’s a piano-rock number with power chords that telegraph inspiration and triumph. It’s also jarringly close to the old Foreigner hit “Cold As Ice.” So as Whitman walks onstage in a black pantsuit, beaming and waving, dimpled and winsome as a valedictorian, the opening lyrics seem to ring out:

She’s as cold as ice

She’s willing to sacrifice our love

“Well, I am delighted to be here,” she starts, reading from two pieces of paper she has carefully placed on a podium. She is tall and almost teetering in heels, but her delivery is poised, crisp, and studied. A native of Long Island, top ten in her high-school class, a Princeton grad with an M.B.A. from Harvard, Whitman has been in California on and off since 1981 but still hasn’t lost her blue-blood elocution. “You are a symphony in bluuuue. It’s remarka-bulll …”

It’s acknowledged among her own staff that Whitman has had trouble connecting with crowds. After a major gaffe last fall, when she stumbled trying to explain why she may not have voted until her mid-forties, she limited her press exposure, letting her multi-million-dollar campaign production serve as prosthetic charisma. Last month, she broke the all-time record for personal money spent on a campaign, $119 million (now she’s up to $140 million), but she is currently as much as seven points down in the polls, partly the result of allegations that she knowingly employed an illegal alien as a housekeeper and then fired her when she began her campaign for governor.

The plushness of the campaign is everywhere in evidence. A dozen advance men with Secret Service–style earbuds curling from their blazers buzz around the perimeter. There are chipper volunteers handing out copies of a 46-page magazine that looks like a special edition of BusinessWeek dedicated exclusively to Meg Whitman. Inside are photos of her looking willowy and warm, listening intently to suburban moms and Latino fruit-pickers alike. It is chock-full of bullet points and graphs, like a benevolent quarterly report. “Of the 38 million people living in California,” reads one item, “144,000 are paying almost 50 percent of the state’s personal income tax.”

Whitman’s plan for California is straight from the Reagan playbook: cutting taxes to stimulate the economy and bringing private-sector discipline to the education system. So far, she has said she’ll eliminate 40,000 jobs from the government payroll and form legislative panels to address the intractable state budget—ideas viewed as hopelessly naïve in Sacramento, where the governor has little authority over the Legislature and political veterans wait with mild bemusement to hear which 40,000 jobs Whitman plans to get rid of.

Her political identity, built on having taken eBay from a start-up to a nearly $8 billion company using advanced branding techniques, is itself a marvel of corporate branding. Her campaign slogan, “Meg 2010: A New California,” appears on posters against a misty, pearly image of Yosemite National Park. Her official logo, embedded on her magazines and on TV ads, is a rectangular stamp with a silhouette of a mountain range at dawn—a brazen recycling of the logo of L.L. Bean, the Maine-based outfitter, telegraphing environmental friendliness in a catalogue-smooth gloss. It’s cheerful, certainly, but it’s not a great Californian burst of optimism, like Reagan’s Morning Again in America, and it seems a little wan beside the chiaroscuro that is California in its current state of decay. And what’s behind all of Whitman’s gloss is something veteran California political hands are trying to figure out nowadays. “I don’t know anyone who really knows her,” says Steve Merksamer, a Republican lawyer in Sacramento who served in the administrations of two former state governors.

Whitman’s interest in politics was a late-life occurrence. Mitt Romney, her boss at Bain & Co. in the early eighties, and now a key mentor, encouraged her after the presidential campaign in 2008, when she served as an economic adviser to Senator John McCain, alongside the other queen of California tech, former Hewlett Packard CEO and Republican Senate candidate Carly Fiorina. The two women gained buzz in the party in 2008, exemplifying the new Republican strain: tough, female, no-nonsense. Both came with cutthroat reputations, especially Whitman, whom some former associates describe as tyrannical, pointing to her infamous $200,000 settlement with an eBay employee after an incident in which Whitman was alleged to have shoved her. Early focus groups for Whitman’s campaign found her cold and remote. “No matter how many smart people are in a room, she thinks not only is she the smartest, but she is smarter than all of them put together,” says a former colleague.

Whitman and Fiorina have fought to see who can transform the tech-queen story line into political gold. Early on, during a McCain-campaign meeting, Whitman asked Fiorina to take notes during a presentation Whitman was giving—never a great way to make friends. Their mutual dislike is an open secret. When a local reporter asked Whitman why she wasn’t sticking around for Fiorina’s speech at the state’s GOP convention the next day, Whitman said, “I’ve got some things I’ve got to do tomorrow. Tomorrow is really Carly’s day. She’s headlining the lunch, and I’m thrilled for her.”

In late August, after a summer in which Whitman campaigned nonstop and spent millions and Brown held few rallies and spent almost no money, Whitman had only managed a tie, and the press was wondering whether she’d stalled out. Asked during the press conference how she felt about a tie, less $100 million, Whitman said, “I’m thrilled to death.”

The Dream is California’s original natural resource, what everything else is built on, and California’s political class was wondering what would happen to the state if it somehow disappeared.

“Did I tell you the story about Queen Califia?”

I’m talking to Bob Hertzberg, a prominent Democrat and lawyer whose 25th-floor office overlooks the golden-brown haze of Los Angeles. A former state assemblyman, Hertzberg tutored Arnold Schwarzenegger in California politics and history when the governor took office in 2003. From his overstuffed bookshelves, he pulls out a dusty volume and settles into his leather chair.

“In 1540, one of the great Spanish books of the time was a book called The Exploits of Esplandian,” he intones, flipping through the pages. “The book centers around Queen Califia, a black Amazon woman draped in gold, of an island called California, which was ruled by these black women, naked women, dressed in gold.

“So when the Spanish sailors came and saw the coast in 1540, this was what was in their mind’s eye. California. Hence the name. That’s how we got the name. Queen Califia’s island.

“And when you think about it, it has always been the land that has been the inspiration. At every level. The land rushes, the gold rush. All this stuff about the natural resources. That’s what the beauty of this thing is.

“The question I have is: Globalization—will it tear it apart? I don’t know.”

“Every man’s fantasy!” says Carly Fiorina, who collected a golden parachute worth around $42 million when she stepped down from HP in 2005. She’s just heard the story of Queen Califia for the first time.

“I moved here from New York when I was 7, and California was this exotic, exciting place where you went to do something new,” she says. “We had orange trees in our front yard, it was so exotic.

“When my mother told us we were moving to California, I remember bursting into tears. It sounded so far away. My brother said, ‘Do they speak English there?’ It was like it was a foreign country. Of course, when you get there, you fall in love with it.”

Then what happened?

“I really think California is the test case for what happens when you keep raising taxes on a smaller and smaller group of people, and you keep layering on regulation after regulation after regulation, and you keep enriching entitlements—and what’s the result of that?”

She reels off a litany of terrifying statistics. Twenty-three counties with 15 percent unemployment. Los Angeles, close to bankrupt. City of Vallejo, bankrupt. If her opponent, Democratic senator Barbara Boxer, remains in office, Fiorina predicts “more of the same, only worse.”

Sounds like the Apocalypse.

“She wants a new California,” says Jerry Brown. “I want the California of my forebears.”

“Yes. Absolutely.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger, governor of California, knows about apocalypses, having battled in them on both sides of the good-evil dichotomy. But that was the future and this is now.

“So you go to the Central Valley,” the governor tells me, “and people say, ‘Governor, we have this high unemployment rate …’

“In Mendoda? What is it?”

“Mendota,” says an aide.

“ ‘Forty percent unemployment rate. Why aren’t you turning on the water? We need the water for our farms, and we can put everyone to work.’

“And you say, ‘Okay, let me talk to the federal government in this.’

“ ‘What do you mean, the federal government? You just go there, I know exactly where it is, and you turn on da pump!’

“I say, ‘This is not an action movie. I’m sorry to disappoint you.’

“But in an action movie, the scene would go: ‘Yes! Come with me and help me!’ And then we walk to the pump, to the station, and then we go and then we cut the chain—no, wait a minute, a movie: We rip the chain, there’s no cutting. ‘Take this lever and pull it down!’ And then we see a close-up of the water, whoosh, coming out, and then you see—cut—all the farmers. Green. The water. There’s hundreds of farmers, a sea of farmers working, and getting all the shade from the heat, and all the water drinking, and all this kind of stuff.

“That’s the scene. But that’s a movie, that’s not the reality. Because in reality, I have to negotiate with the federal government, and the federal government, with the Endangered Species Act, they will have their own dialogue, and it gets very complicated. And so now we are suffering because of that. But then you can take it to the court, but the court has already struck down and said, ‘No, we turn off the pump because the smelt and the salmon is more important than the people,’ and there is all of this stuff going on.

“So it is not anymore what you think it is.”

“Money! money! money!”

Slam! Slam! Slam!

It’s Brown again, claiming he’s going to save the Dream with the help of … reality. I’ve asked him how, as governor, he’d resist the demands of the all-powerful public-employee unions, which soak up 80 percent of the state’s tax revenue in salaries and pensions and who have given Brown roughly $14 million to go up against Meg Whitman. Whitman claims Brown is “bought and paid for” by “union bosses.” So now Brown is doing an imitation of a union boss demanding money at a table much like the one we’re sitting at.

“This is a table, right?”

Pound, pound, pound.

“I can’t break this table. No matter how hard you pound the table, you’re not going to produce money. The money! Is! The money!”

Slam! Slam! Slam!

“Now. There’s only one thing you can do. And that is, through a process of smoke and mirrors, through pretending revenues are coming when they probably aren’t, and pretending cuts are going to be effectuated when they’re not, you can kind of go from year to year. But because we’ve been doing that for so many years, we’re just about at the end of that rope, so the next governor is going to be the truth-teller, saying, ‘Come to Jesus, here’s what we gotta do.’ It’s going to be very difficult.”

Brown has said he won’t raise taxes, unless the voters agree to it. Earlier this year, he was quoted saying he had a plan, but he couldn’t reveal it until after the election. Whitman pounced on it as a sign of Brown’s lack of a plan, or just a secret plan to raise taxes. His overall message: a tough love Californians can rely on, even if the majority of the electorate is too young to remember the days when he entertained the idea of making California a launchpad for a mass migration to space.

Brown’s campaign strategy appears to be, let Whitman spend all her money while Brown leans back and declares her a spendthrift and a dilettante.

Kevin Starr, the USC historian, who went to high school with Brown, calls Brown’s non-efforts a “Zen campaign,” which seems to acknowledge that politics itself, the function and purpose of it, has “been erased in California.” Or, put another way, why have a plan if plans aren’t going to work?

“It’s an empty blackboard,” Starr says.

Everyone thinks Brown is running to crown the family legacy in California. In recent months, he’s been talking more about his father, Pat Brown Sr., and his nieces are producing a documentary about their grandfather, how he built up the higher-education and highway systems before he was defeated by Reagan in 1966. Brown is said to have disliked his father, openly contrasting himself to the senior Brown during his first campaign for governor in 1974. But he regrets that, says one associate, and sees more clearly what his father did right.

At one point Brown grabs a framed black-and-white picture of his great-grandfather, a bearded sheepherder on the family ranch outside Sacramento. “My great-grandfather drove the stagecoach from Placerville to Sacramento,” he says. “Came in 1852 by covered wagon.”

Meg Whitman from Long Island: Does she get California?

“I don’t know what she gets,” Brown says, going quiet. “She’s a marketer. She wants to rebrand California. She wants a New California. I see the California of my forebears.”

One could not have scripted this, but there it is: California is going down in a haze of pot smoke.

“We’ve just been waiting patiently,” says Richard Lee, a pale man in black clothes and dark shades, rolling his wheelchair through the streets of downtown Oakland. “I sound like the Grinch, you know, waiting for the economy to go bad and rooting for it to. But on the one hand, that’s what it’s going to take to wake people up.”

Lee is the guy who put up $1.5 million of his own money to get Proposition 19 on the ballot in California. It proposes to legalize, regulate, and tax marijuana, thereby simultaneously easing the budget crisis and achieving the lifelong dream of stoners everywhere.

In 1990, Lee was working as a lighting technician at an Aerosmith concert when he fell and broke his back, an accident confining him to a wheelchair for life. His discovery of marijuana as therapy transformed him into an avid pot activist and entrepreneur. After twenty years, Lee says, the recession is the squeeze play he’d imagined could finally push the state to legalize. As it stands, polls show the electorate in favor of the proposal, but not a single major politician running for office—not Senator Barbara Boxer, not Brown, Whitman, or Fiorina—supports Prop 19.

“It should be a Republican issue,” says Lee, whose parents are Goldwater Republicans in Houston. “It is less government and more responsibility. Palin said it’s not a big deal.” The amount of tax revenue that legalized pot would create is a matter of debate, with estimates ranging from $300 million annually to a fantastic $1.4 billion. The Rand Corporation conducted a study that predicted that the price of an ounce of pot could drop precipitously and produce less tax revenue than believed. But nobody really knows.

Lee appears to partake of the product. He showed up an hour and a half late to our interview and forgot the keys to the offices and classrooms and indoor pot farms that are part of his sprawling marijuana education, marketing, and distribution mecca, called Oaksterdam. It’s a sleepy downtown area that Lee is trying to develop into a legalized-pot haven akin to Amsterdam, complete with cafés and shops and even a college, Oaksterdam University, where you can learn to cultivate indica or study marijuana laws (“Featuring the very best instructors the cannabis industry has to offer,” declares an advertisement).

To the Easterner, all this state-sponsored weed is exotic stuff. When I meet Lee at Coffeeshop Blue Sky, his dispensary, the Grateful Dead is playing over the stereo and a steady stream of customers are filing in, white guys in baseball caps and black church ladies just out of Sunday service, flashing medical cards and strolling to the back room where a young woman at a teller window sells five varieties of weed for about $40 for an eighth of an ounce. I’m shown a tray of pot-infused food items: peanut butter, German chocolate-truffle cake, ten flavors of freeze-dried drinks, peanut brittle, hard candy, olive oil, honey. There are pre-rolled joints in packaging reminiscent of a CVS thermometer. There’s a color catalogue detailing every variety of pot plant you can buy, from “LA Confidential” to “Black Kush” to “Odyssey,” which promises a “long-lasting head high.”

Later, Lee and I visit the “student union” of Oaksterdam U., a dimly lit room where people are watching pro football on a big-screen TV while inhaling pot from smokeless vaporizers. It’s as boring and benign as any midtown pub. As our interview winds down, Lee becomes increasingly distracted. During lunch, he’s so engrossed in a copy of Motor Trend magazine that he stops responding to my questions.

David Boies, the Democratic New York lawyer of Bush v. Gore fame, is barefoot and wearing swim shorts, a baseball cap pulled over his wet hair. We’re in an oceanside bungalow in Newport Beach, where Boies is at a family reunion. The Pacific is shimmering through the open door behind him. Golden-skinned people glide by on Rollerblades.

Two weeks before, Boies and his unlikely legal partner, Republican Ted Olson, George W. Bush’s lawyer in 2000, won a major victory when a district court judge declared Prop 8, the anti-gay-marriage ballot initiative, unconstitutional. Opponents promptly appealed, sending the suit brought by two gay couples to the Ninth Circuit Appeals Court, but keeping marriage between gays and lesbians illegal until the case is resolved. As it stands, the law has engendered an untenable legal purgatory unlike anything else in America.

“That’s one of the really strange things about California right now,” Boies marvels. “You have about 18,000 gay and lesbian couples who are married. And the court of California said those marriages are valid. Now their neighbors can’t get married … In fact, if the gay couple that’s married get divorced, they can’t remarry. They can’t even remarry themselves. It makes no sense.”

His opponents, fighting on behalf of Prop 8, are faced with a crucial decision: whether to fight the case all the way to the Supreme Court, where Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was born and raised in Sacramento and whose rulings were cited favorably in the district court’s decision, could be decisive in making it federal law, thereby making gay marriage legal in not just California but, eventually, the whole country.

Gay marriage is about civil rights, of course, but in California it’s also about the state’s identity as a launchpad for progress, the mass migration to the future. And if California can’t light the way to new realms of personal liberty, it undermines an article of faith woven into the Dream. Maybe for that reason, the opposition is actually divided on whether California or the nation is the ultimate prize. California led the way in banning restrictions on blacks, Jews, and Catholics owning property in America. It took interracial marriage to the State Supreme Court and won.

“I do feel a connection to that lineage,” Boies says. “I think it’s appropriate that California should lead the way. It’s had a progressive tradition for 100 years.”

Below a 30-foot-wide chandelier in a fabulously ostentatious neo-Baroque Hyatt Hotel in downtown San Diego, Meg Whitman is standing at a glass podium. It’s the California Republican Party convention.

“You know, I was doing a little fund-raising in New York not too long ago,” Whitman says after her theme song, “and you know who’s as excited about this election as we are?

“People in New York,” she answers.

“Because they have suffered the financial reforms that are going to crimp our ability to raise capital, and they want California to turn the corner. They want us to elect a Republican governor, they want us to set an example for the United States of America!”

“Whoo!” cry the Republicans, as they carve into their chicken dinners.

You can practically feel Whitman’s campaign staff wince, given her ties to Goldman Sachs, which allowed her to make $1.78 million in questionable IPO profits while she was a board member. That became a line of attack for her primary opponent, Steve Poizner. But for the moment, it fits into Whitman’s assault on Jerry Brown as the union shill who will kill big business in California and further decimate the economy. To set up her arrival onstage, the audience is shown an anti-Brown film in which Indian sitar music and swirling, psychedelic colors are edited over a TV clip of Brown saying, “Government regulation is a response to the inhumanity, the juggernaut quality to these alien institutions called corporations.”

The Republican Party in California is considered something of a joke, its voter registrations dwindling for the last decade. Whitman is here to throw some red meat to the faithful and beat a fast retreat, before anybody asks her about her immigration views, which are left of Arizona’s, and therefore far left of California’s right wing. Schwarzenegger is nowhere mentioned, which is curious since Whitman’s rhetoric is crafted by the same people who engineered Schwarzenegger’s 2003 win, a group of Republican consultants associated with former governor Pete Wilson, as well as media-savvy Republican strategist Mike Murphy, who recently sold a script to HBO about political consultants.

Whitman has regularly backhanded Schwarzenegger on the trail, and in an interview, she criticizes him for having tried to do too many things. Contrasting herself to Schwarzenegger, Whitman says she understands that “you’re only as good as the people who work for you.”

But the people who advised and managed Schwarzenegger during his most dramatic failures, I point out, are now on her payroll, advising her on strategy. “In the end you have to be accountable for the people you hire,” she says, “and the advice you take or don’t take.”

Whitman, with her array of advisers and pollsters sifting the ones and zeros of the electorate, ultimately sees California as a numbers game. A GOP consultant I spoke with says Whitman versus Brown is really science versus art, and Whitman has “bought the laboratory.”

And the laboratory has figured out just about everything except … the story. As her GOP speech reaches its climax, Whitman addresses why she’s spending millions of dollars to win this election. “I have put my money into this race,” she acknowledges, “but more than that, I have put my heart and soul into this struggle.”

For a minute, there is a curious charge in the room. It sounds like she’s about to divulge an emotional purpose heretofore unseen in her ironsided campaign juggernaut.

“After twenty months, the pundits still ask why I am running for governor of California,” she says, echoing exactly what pundits in the press gallery are thinking.

“The reason I am running for governor of California is”—the $100 million moment of truth, the beating heart of Whitman’s passion, revealed—“I refuse to believe our state cannot be better than it is.”

“I say, ‘This is not an action movie, I’m sorry to disappoint you,’ ” says Arnold Schwarzenegger.

When he takes a seat at the end of the 25-foot conference table, he’s like a human boulder in an olive-green suit and red tie, wearing alligator loafers and a watch with a face roughly the size of a coffee mug.

“California will always be the dream state,” says Schwarzenegger, sitting in his wood-paneled office adorned with countless pictures of Ronald Reagan, his hero. “I never say anywhere that the dream is dead. Someone else said that or somebody put the words in my mouth, because I would never say that. Because to me, the dream is the hope that you have, and the hope and the dream and the vision is always bright.”

Nowadays, Schwarzenegger’s high-watt optimism can seem like a comic charade amid the state’s smoldering ruins. But even Schwarzenegger, the indefatigable optimist, the onetime “Governator” whose epic California story vaulted him to power in 2003, has the air of a weary actor after a long, disastrous production. Twenty-two percent approval rating. Given his budget woes, when he bids me heft his prop sword from the Conan the Barbarian film, kept in a case near his office door, his requisite punch line feels drained of a former thrust: “I use it to cut da budget.”

But Schwarzenegger is surprisingly candid about the pitfalls of the office he’s held for the term-limited seven years, a cautionary tale for the candidates vying to replace him. “The voters can change what is a priority very quickly,” he says, comparing the governing of California to, variously, steering the Titanic, skiing a slalom course, starring in a bad movie, and, of course, bodybuilding. When his goal was to become Mr. Universe in the late sixties, he explains, “nobody said in the middle, ‘Whoah, whoah, whoah, become the soccer champion.’ Wait a minute, I can’t now run as fast with these legs that are lifting 500 pounds! C’mon, don’t throw me off here. That’s why I got out of soccer.”

In this metaphor, the economic collapse was the surprise soccer challenge, which seemed to blow up Schwarzenegger’s efforts to slash the budget with his Conan sword while also passing progressive reforms, forcing him to make jobs the top, and really only, priority.

“But in the meantime, this Titanic,” he says. “You can only deviate a little bit, and you say, ‘Okay, I see the job thing, let me work on that also, but in the meantime don’t let me get off track here because I could be very successful with this.’ ”

Schwarzenegger’s decline in the polls is less about him than it is about a lost faith in the possibility of fixing California. The California Legislature, which requires a two-thirds vote to raise taxes or pass a budget, is composed of hard-left and hard-right factions, each forced into extremes by gerrymandering and term limits.

“You step on somebody’s else’s feet, and the war begins,” says Schwarzenegger. “And they try to derail you and make you look small and reduce you and spin it a different way. Instead of trying to be fiscally responsible, you’re taking food out of poor people’s mouths.”

Frustrating? Recall the infamous letter Schwarzenegger sent to the State Assembly, along with a veto of a development project, in which the first letter of each line together spelled FUCK YOU.

(Among Schwarzenegger’s victories in office were structural fixes meant to defuse political polarization, like redistricting reform and open primaries. Considering his legacy, he compares himself to Jerry Brown’s father. “They look back, man, this guy, we didn’t know it, this guy created some great action,” says Schwarzenegger, “but back then we didn’t realize it.”)

When a law is finally passed in Sacramento, lawsuits are next. “Judges make a lot of the decisions,” says Schwarzenegger. “When you talk about the slalom course, there were some gates thrown in while you’re going down the course. You say, ‘Wait a minute, where did that gate come from?’ ”

Then there are the multitudinous ballot initiatives, which have swung the state around by its own tail for years. They’re blamed for some of the laws that permanently warped California, like Prop 13, the 1978 vote to cap property taxes, which made income tax the main source of state revenue, thus tying California’s fortunes to the booms and busts of the economy. There are also propositions to reverse laws already passed, like Prop 23, a ballot to temporarily suspend the crown jewel of Schwarzenegger’s legacy, climate-change legislation. Whitman has waffled on Prop 23.

Schwarzenegger has been excommunicated from the Republican Party in California since 2005, when he lost on a series of fiscally conservative initiatives following an expensive battle with the unions, which burned $120 million trying to defeat him. At the time, his staff was made up of all the people running Meg Whitman’s campaign.

“Having not been in politics, I really didn’t know all the players available,” says Schwarzenegger. “So you had a little bit of the leftover Pete Wilson people and some new ones, but I really never felt until two years later that now I have my team.”

Maria Shriver, Schwarzenegger’s Democrat wife, blamed her husband’s staff for mismanagement and, after pushing them out, became her husband’s unofficial headhunter. The late Tim Russert recommended she hire Steve Schmidt, a senior official in the Bush White House, to help her husband win reelection in 2006. To court recalcitrant Democrats, Schwarzenegger hired a gay Democrat from the Bay Area named Susan Kennedy as his chief of staff. She pushed through the climate bill, which, along with Schwarzenegger’s pledge not to raise taxes, helped him get reelected in 2006.

Then the economy cratered and Schwarzenegger reneged on the pledge and raised taxes. His popularity plummeted.

Schwarzenegger is virtually alone these days. Gray Davis, the highly unpopular governor ousted in the circuslike recall of 2003, has been an adviser to him. In the end, Schwarzenegger compares the economy to a bad movie he’s blamed for having starred in. “If you come out with a movie and you’re the star, you get all the credit in the world and you’re the one that has created this success,” he explains. “And if the movie goes in the toilet, then you get dumped on that you’re not hot anymore, you’re history, even if the acting was good, the directing was bad, the script was bad, but your acting was brilliant. That’s just the way it works.”

Are the glory years of California over? I pose this question to Steve Merksamer, the Sacramento lawyer who’s a former chief of staff to two-term governor George “Iron Duke” Deukmejian. Merksamer has a long memory. He was around when Reagan fired two staffers in 1967 after a report surfaced of a gay sex orgy in a Lake Tahoe cabin.

“If you had asked me this question two years ago, I would have said the pessimism is overdone,” he says in his office overlooking the lawn in front of the statehouse. “It’s the same old California, maybe with some more complex problems. But you ask me the question today, I would say, I don’t know. It’s the first time in 40 years that I would say I don’t know. I can’t look you in the eye and say it’s the same California I grew up in, and that’s an optimistic, can-do California.”

“Merksamer!” grunts Schwarzenegger when I tell him what Merksamer said. “Just look at him.”

Schwarzenegger then goes into an impression of Merksamer, grimacing, mocking his bushy white hair. His aides fall into hysterics.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all that a verklempt guy like that says something like that,” he says. “I mean, Merksamer. You can see in the face that there is no optimism, there is no joy, there is no juice there.

“This is not me,” he says. “But, you know … he’s a good lawyer.”

“Out of constraints comes creativity,” Jerry Brown tells me, trying to explain how California goes forward. He’s still doing it, still dreaming. Money, or lack of it, can’t kill the dream. California’s not old. Look at Brown, he’s 72 and still going. If Brown can rise again, so can California. That’s his pitch, when it comes down to it. It’s never too late. “He’s 72, and he can be president,” Brown himself marveled while watching John McCain win a primary against Mitt Romney in 2008. “If he can be president at that age, so can I.”

In Brown, the Dream will never die—he is the Dream, in all its loopy optimism and brilliant delusions. Maybe nothing will get fixed. But no one ever got shot into space, either. Maybe it doesn’t matter.

Brown leans back, looks down, touches the table that he’s been pounding all morning.

“This used to be a railroad tie,” he says. “Now it’s a table.”

It’s a Zen moment. The sound of one hand clapping. Brown’s eyes narrow. You can see the gears in his head turning. A new idea. A New California?

“I think I got this in Pennsylvania.”