This article was featured in Reread: New York Hustlers, a newsletter miniseries that resurfaces classic tales of scammers, grifters, and strivers from the New York archives. To read more stories like this, sign up here.

During the early seventies, when for a sable-coat-wearing, Superfly-strutting instant of urban time he was perhaps the biggest heroin dealer in Harlem, Frank Lucas would sit at the corner of 116th Street and Eighth Avenue in a beat-up Chevrolet he called Nellybelle. Then living in a suite at the Regency Hotel with 100 custom-made, multi-hued suits in the closet, Lucas owned several cars. He had a Rolls, a Mercedes, a Corvette Sting Ray, and a 427 muscle job he’d once topped out at 160 mph near Exit 16E of the Jersey Turnpike, scaring himself so silly that he gave the car to his brother’s wife just to get it out of his sight.

But for “spying,” Nellybelle was best.

“Who’d think I’d be in a shit $300 car like that?” asks Lucas, who claims he’d clear up to $1 million a day selling dope on 116th Street.

“One-sixteenth Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenue was mine. I bought it. I ran it. I owned it,” Lucas says. “When something is yours, you’ve got to be Johnny-on-the-spot, ready to take it to the top. So I’d sit in Nellybelle by the Roman Garden Bar, cap pulled down, with a fake beard, dark glasses, long wig … I’d be up beside people dealing my stuff, and no one knew who I was …”

It was a matter of control, and trust. As the leader of the heroin-dealing ring called the Country Boys, Lucas, older brother to Ezell, Vernon Lee, John Paul, Larry, and Leevan Lucas, was known for restricting his operation to blood relatives and others from his rural North Carolina area hometown. This was because, Lucas says, in his down-home creak of a voice, “a country boy, he ain’t hip … he’s not used to big cars, fancy ladies, and diamond rings. He’ll be loyal to you. A country boy, you can give him any amount of money. His wife and kids might be hungry, and he’ll never touch your stuff until he checks with you. City boys ain’t like that. A city boy will take your last dime, look you in the face, and swear he ain’t got it … You don’t want a city boy — the sonofabitch is just no good.”

Back in the early seventies, there were many “brands” of dope in Harlem. Tru Blu, Mean Machine, Could Be Fatal, Dick Down, Boody, Cooley High, Capone, Ding Dong, Fuck Me, Fuck You, Nice, Nice to Be Nice, Oh — Can’t Get Enough of That Funky Stuff, Tragic Magic, Gerber, The Judge, 32, 32-20, O.D., Correct, Official Correct, Past Due, Payback, Revenge, Green Tape, Red Tape, Rush, Swear to God, PraisePraisePraise, KillKillKill, Killer 1, Killer 2, KKK, Good Pussy, Taster’s Choice, Harlem Hijack, Joint, Insured for Life, and Insured for Death were only a few of the brand names rubber-stamped onto cellophane bags. But none sold like Frank Lucas’s Blue Magic.

“That’s because with Blue Magic, you could get 10 percent purity,” Lucas asserts. “Any other, if you got 5 percent, you were doing good. We put it out there at four in the afternoon, when the cops changed shifts. That gave you a couple of hours before those lazy bastards got down there. My buyers, though, you could set your watch by them. By four o’clock, we had enough niggers in the street to make a Tarzan movie. They had to reroute the bus on Eighth Avenue. Call the Transit Department if it’s not so. By nine o’clock, I ain’t got a fucking gram. Everything is gone. Sold … and I got myself a million dollars.

“I’d sit there in Nellybelle and watch the money roll in,” says Frank Lucas of those near-forgotten days when Abe Beame lay his pint-size head upon the pillow at Gracie Mansion. “And no one even knew it was me. I was a shadow. A ghost … what we call down home a haint … That was me, the Haint of Harlem.”

Twenty-five years after the end of his uptown rule, Frank Lucas, now 69, has returned to Harlem for a whirlwind retrospective of his life and times. Sitting in a blue Toyota at the corner of 116th Street and what is now called Frederick Douglass Boulevard (“What was wrong with just plain Eighth Avenue?” Lucas grouses), Frank, once by his own description “tall, pretty, slick, and something to see” but now stiff and teetering around “like a fucking one-legged tripod,” is no more noticeable than when he peered from Nellybelle’s window.

Indeed, few passersby might guess that Lucas, at least according to his own exceedingly ad hoc records, once had “something like $52 million,” most of it in Cayman Islands banks. Added to this is “maybe 1,000 keys of dope on hand” with a potential profit of no less than $300,000 per kilo. Also in his portfolio were office buildings in Detroit, apartments in Los Angeles and Miami, “and a mess of Puerto Rico.” There was also “Frank Lucas’s Paradise Valley,” a several-thousand-acre spread back in North Carolina on which ranged 300 head of Black Angus cows, including a “big-balled” breeding bull worth $125,000.

Nor would most imagine that the old man in the fake Timberland jacket was a prime mover in what federal judge Sterling Johnson, who in the seventies served as New York City special narcotics prosecutor, calls “one of the most outrageous international dope-smuggling gangs ever … an innovator who got his own connection outside the U.S. and then sold the stuff himself in the street.”

It was “a real womb-to-tomb operation,” Johnson says, and the funerary image fits, especially in light of Lucas’s most culturally pungent claim to fame, the so-called Cadaver Connection. Woodstockers may remember being urged by Country Joe & the Fish to sing along on the “Fixin’ to Die Rag” — “Be the first one on your block to have your boy come home in a box.” But even the most apocalyptic-minded sixties freak wouldn’t guess the box also contained a dozen keys of 98 percent-pure heroin. Of all the dreadful iconography of Vietnam — the napalmed girl running down the road, Calley at My Lai, etc., etc. — dope in the body bag, death begetting death, most hideously conveys ‘Nam’s spreading pestilence. The metaphor is almost too rich. In fact, to someone who got his 1-A in the mail the same day the NVA raised the Red Star over Hue City, the story has always seemed a tad apocryphal.

But it is not. “We did it, all right … ha, ha, ha … ” Lucas chortles in his dying-crapshooter’s scrape of a voice. “Who the hell is gonna look in a dead soldier’s coffin? Ha ha ha.”

I had so much fucking money — you have no idea,” Lucas says, riding around Harlem, his heavy-lidded light-brown eyes turned to the sky in mock expectation that his vanished wealth, long since seized by the Feds, will rain back down from the heavens.

Aside from the hulking 369th Infantry Armory, where Lucas and his boys unloaded trucks they’d hijack out on Route 1-9, little about Harlem has remained the same. Still, nearly every block summons a memory. Over at Eighth Avenue and 113th Street, that used to belong to Spanish Raymond Marquez, the big numbers guy. On one Lenox Avenue corner is where “Preacher got killed”; on the next is where Black Joe bought it. Some deserved killing, some maybe not, but they were all dead just the same.

In front of a blue frame house on West 123rd Street, Lucas stops and gets nostalgic. “I had my best table workers in there,” he says, describing how his “table workers,” ten to twelve women naked except for surgical masks, would “whack up” the dope, cutting it with “60 percent mannite and 40 percent quinine.” The petite, ruby-haired Red Top was in charge. “I’d bring in three, four keys, let Red go do her thing. She’d mix up that dope like a rabbit in a hat, never drop a speck … Red … I sure do miss her …”

At 135th and Seventh, Lucas stops again. Small’s Paradise used to be there. Back in the day, there were plenty of places — Mr. B’s, Willie Abraham’s Gold Lounge, the Shalimar. But Small’s was the coolest. “Everyone came by Small’s … jazz guys, politicians. Ray Robinson. Wilt Chamberlain, when they called the place Big Wilt’s Small’s Paradise …” At Small’s, Lucas often met his great friend the heavyweight champ Joe Louis, who later appeared nearly every day at Lucas’s various trials, expressing outrage at how the state was harassing “this beautiful man.” When the Brown Bomber died, Lucas, who once paid off a $50,000 tax lien for the champ, was heard weeping into a telephone, “my daddy … he’s dead.” It was also at Small’s, on a winter’s night in the late fifties, that Frank Lucas encountered Howard Hughes.

“He was right there, with Ava Gardner … Howard Hughes, the original ghost — that impressed me.”

In the end, the tour comes back to 116th Street. It’s now part of Harlem’s nascent real-estate boom, but when Frank “owned” this street, “you’d see junkies, nodding, sucking their own dicks … heads down in the crotch. People saw that, they knew that shit was good.”

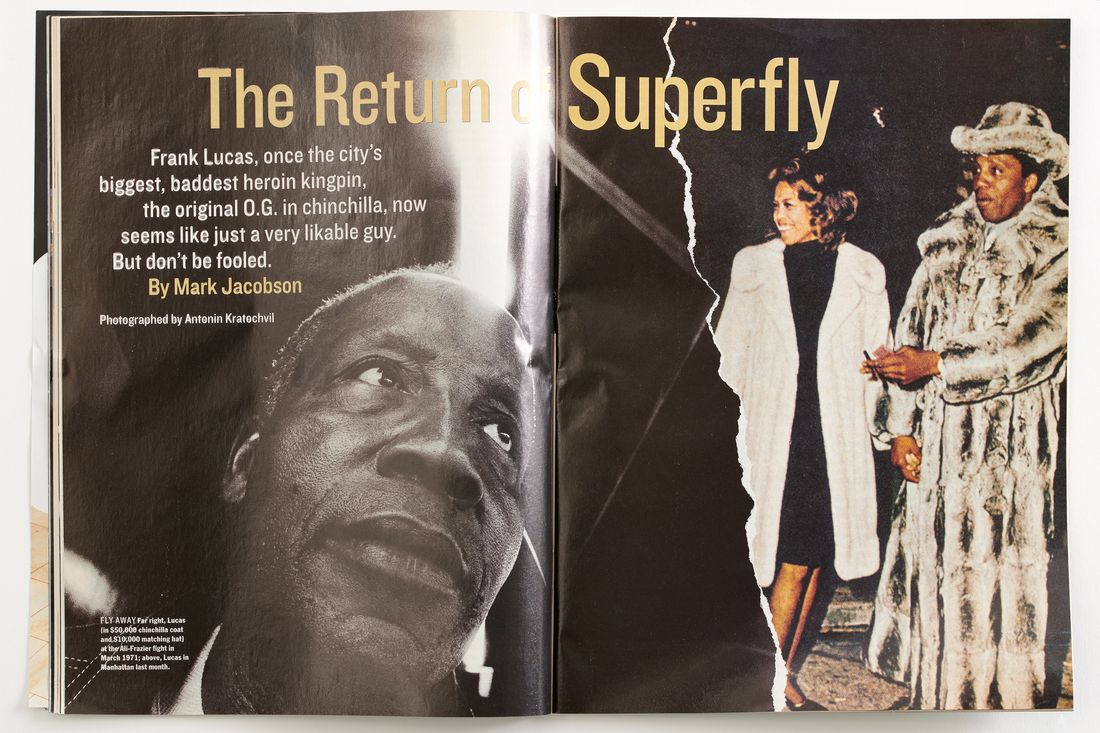

A moment later, Lucas looks up. “Uh-oh, here come the gangstas,” he shouts in mock fright, as a trio of youths, blue kerchiefs knotted around their heads, go by blaring rap music. Lucas is no fan of “any Wu-Tang this and Tupac that.” Likewise, Lucas, who thought nothing of spending $50,000 on a chinchilla coat and $10,000 on a matching hat, doesn’t go for the current O.G. styles. “Baggy-pants bullshit” is his blanket comment on the thug-life knockoffs currently in homeboy favor.

“I guess every idiot gets to be young once,” Lucas snaps, driving half a block before slamming on the brakes.

“Here’s something you ought to see,” the gangster says, pointing toward the curb between the Canaan Baptist Church and the New Africa House of Fish. “There’s where I did that boy … Tango,” he sneers, his large, squarish jaw lanterning forward. “I told you about that, didn’t I?”

Of course he had, only days before, in minute, hair-raising detail.

For Lucas, the incident, which occurred in “the summer of 1965 or ‘66,” was strategy. Strictly business. Because, as Lucas recalls, “when you’re in the kind of work I was in, you’ve got to be for real. You’ve got to show what you’re willing to do.”

“Everyone, Goldfinger Terrell, Willie Abraham, Hollywood Harold, was talking about this big guy, this Tango. About six five, 270 pounds, quick on his feet … He killed two or three guys with his hands. Had this big bald head, like Mr. Clean. Wore those Mafia undershirts. Everyone was scared of him. So I figured, Tango, you’re my man.

“I went up to him, asked him if he wanted to do something, some business. I gave him $5,000 worth of merchandise. Because I know he was gonna fuck up. That’s the kind of guy he was. Two weeks later, I go talk to him. ‘Look, man,’ I say. ‘Hey, man, when you gonna pay me?’

“Then, like I knew he would, he started getting hot, going into one of his gorilla acts. He was one of them silverback gorillas, you know, you seen them in the jungle. A silverback gorilla, that’s what he was.

“He started cursing, saying he was going to make me his bitch and he’d do the same to my mama too. Well, as of now, he’s dead. No question, a dead man. But I let him talk. A dead man got a right to say what he wants. Now the whole block is there, to see if I’m going to pussy out. He was still yelling. So I said to him, ‘When you get through, let me know.’ “

“Then the motherfucker broke for me. But he was too late. I shot him. Four times, right through here: bam, bam, bam, bam.

“Yeah, it was right there,” says Frank Lucas, 35 years after the shooting, pointing out the car window. “The boy didn’t have no head. The whole shit blowed out back there … That was my real initiation fee into taking over completely down here. Because I killed the baddest motherfucker. Not just in Harlem but in the world.”

Then Frank laughs.

Frank’s laugh: It’s a trickster’s sound, a jeer that cuts deep. First he rolls up his shoulders and cranes back his large, angular face, which, despite all the wear and tear, remains strikingly handsome, even empathetic in a way you’d like to trust but know better. Then the smooth, tawny skin over his cheekbones creases, his ashy lips spread, and his tongue snakes out of his gate-wide mouth. Frank has a very long, very red tongue. Only then the soundtrack kicks in, staccato stabs of mirth followed by a bevy of low rumbled cackles.

Ha ha ha, siss siss siss. For how many luckless fools like Tango was this the last sound they heard on this earth?

Hearing tapes of our conversations, my wife leaned back in her chair. “Oh,” she said, “you’re doing a story on Satan … ” She said it was like hearing the real interview with a vampire.

“After I killed that boy,” Frank Lucas goes on, gesturing toward the corner on the other side of 116th Street, “from that day on, I could take any amount of money, set it on the corner, and put my name on it. FRANK LUCAS. I guarantee you, nobody would touch it.”

Then Frank laughs again, putting a little extra menace into it. This is just so you don’t get too comfortable with the assumption that your traveling partner is nothing but a limping old guy with a gnarled hand fond of telling colorful stories and wearing $5 acetate shirts covered with faux nascar logos.

Just so you never forget exactly who you are dealing with.

When asked about the relative morality of killing people, selling millions of dollars of dope, and playing a significant role in the destruction of the social fabric of his times, Frank Lucas bristles. What choice did he have? he demands. “Kind of sonofabitch I saw myself being, money I wanted to make, I’d have to be on Wall Street. On Wall Street, from the giddy-up. But I couldn’t have even gotten a job being a fucking janitor on Wall Street.”

Be that as it may, there’s little doubt that when, on a sweltering summer’s afternoon in 1946, Frank Lucas arrived in Harlem, which he’d been told was “the promised land,” his prospects in the legitimate world were limited. Not yet 16 years old, he was already on the run. Already a gangster.

It couldn’t have been any other way, Lucas insists, after the Ku Klux Klan came to the shack where he grew up and killed his cousin. “I couldn’t have been more than 6. We were living back in the woods near a little place they call La Grange, North Carolina. These five white guys come up to the house one morning, big rednecks … they’re yelling, ‘Obadiah … Obadiah Jones … come out. Come out, you nigger …’ They said he was looking at a white girl walking down the street. ‘Reckless eyeballing,’ they call it down there.

“Obadiah was like 12 or 13, and he come out the door, all sleepy and stuff. ‘You been looking at somebody’s daughter. We’re going to fix you,’ they said. They took ropes on each hand, pulled them tight in opposite directions. Then they shoved a shotgun in Obadiah’s mouth and pulled the trigger.”

It was then, Lucas says, that he began his life of crime. “I was the oldest. Someone had to put food on the table. I started stealing chickens. Knocking pigs on their head … It wasn’t too long that I was going over to La Grange, mugging drunks when they come out of the whorehouse. They’d spent their $5 or $6 buying ass, head jobs, then I’d be waiting with a rock in my hand, a tobacco rack, anything.”

By the time he was 12, “but big for my age,” Lucas says, he was in Knoxville, Tennessee, locked up on a chain gang. In Lexington, Kentucky, not yet 14, he lived with a lady bootlegger. In Wilson, North Carolina, working as a truck driver at a pipe company, he started in sleeping with the owner’s daughter. This led to problems, especially after “Big Bill, a fat, 250-pound beer-belly bastard” caught them in the act. In the ensuing fight, Frank hit Bill on the head with a piece of pipe, laying him out.

“They didn’t owe me but $100, but I took $400 and set the whole damned place on fire.” Told by his mother to run and keep running, he bummed his way northward.

“I got to 34th Street. Penn Station. Then took the bus to 14th Street. I went over to a policeman and said, ‘Hey, this ain’t 14th Street. I want to go where all the black people are at.’ He said, ‘You want to go to Harlem … 114th Street!’

“I got to 114th Street. I had never seen so many black people in one place in all my life. It was a world of black people. “And I just shouted out: ‘Hello, Harlem … hello, Harlem, USA!’ “

People told him to be smart, get a job as an elevator operator. But once Frank saw guys writing policy numbers, carrying big wads, his course was set. Within a few months, he was a one-man, hell-bent crime wave. He stuck up the Hollywood Bar on Lenox and 116th, got himself $600. He went to the Busch Jewelers on 125th Street, stole a tray of diamonds, broke the guard’s jaw with brass knuckles on the way out. Later, he ripped off a high-roller crap game at the Big Track Club on 110th. “They was all gangsters in there, Cool Breeze, a lot of them. I walked in, took their money. Now they was all looking for me.”

The way he was going, Frank figures, it took Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, the most famous of all Harlem gangsters, to save his life. “I was hustling up at Lump’s Pool Room, on 134th Street. Eight-ball and that. So in comes Icepick Red. Red, he was a tall motherfucker, clean, with a hat. A fierce killer, from the heart. Freelanced Mafia hits. Anyway, he took out a roll of money that must have been that high. My eyes got big. I knew right then, that wasn’t none of his money. That was my money . . .

“‘Who got a thousand dollars to shoot pool?’ Icepick Red shouted. I told him I’m playing, but I only got a hundred dollars … and he’s saying, ‘What kind of punk only got a hundred dollars?’ I wanted to take out my gun and kill him right there, take his damn money.

“Except right then, everything seemed to stop. The jukebox stopped, the pool balls stopped. Every fucking thing stopped. It got so quiet you could’ve heard a rat piss on a piece of cotton in China.

“I turned around and I saw this guy — he was like five feet ten, five feet eleven, dark complexion, neat, looked like he just stepped off the back cover of Vogue magazine. He had on a gray suit and a maroon tie, with a gray overcoat and flower in the lapel. I never seen nothing that looked like him. He was another species altogether.

“‘Can you beat him?’ he said to me in a deep, smooth voice.

“I said, ‘I can shoot pool with anybody, mister. I can beat anybody.’

“Icepick Red, suddenly he’s nervous. Scared. ‘Bumpy!’ he shouts out, ‘I don’t got no bet with you!’

“Bumpy ignores that. ‘Rack ‘em up, Lump!’

“We rolled for the break, and I got it. And I wasted him. Icepick Red never got a goddamn shot. Bumpy sat there, watching. Didn’t say a word. Then he says to me, ‘Come on, let’s go.’ I’m thinking, who the fuck is this Bumpy? But something told me I better keep my damn mouth shut. I got in the car. A long Caddy. First we stopped at a clothing store — he picked out a bunch of stuff for me. Suits, ties, slacks. Nice stuff. Then we drove to where he was living, on Mount Morris Park. He took me into his front room, said I should clean myself up, sleep there that night.

“I wound up sleeping there six months … Then things were different. The gangsters stopped fucking with me. The cops stopped fucking with me. I walk into the Busch Jewelers, see the man I robbed, and all he says is: ‘Can I help you, sir?’ Because now I’m with Bumpy Johnson — a Bumpy Johnson man. I’m 17 years old and I’m Mr. Lucas.

“Bumpy was a gentleman among gentlemen, a king among kings, a killer among killers, a whole book and Bible by himself,” says Lucas about his years with the so-called Robin Hood of Harlem, who had opposed Dutch Schultz in the thirties and would be played by Moses Gunn in the original Shaft and twice by Laurence Fishburne (in The Cotton Club and Hoodlum).

“He saw something in me, I guess. He showed me the ropes — how to collect, to figure the vig. Back then, if you wanted to do business in Harlem, you paid Bumpy or you died. Extortion, I guess you could call it. Everyone had to pay — except the mom-and-pop stores.”

With Bumpy, Frank caught a glimpse of the big time. He’d drive downtown, to the 57th Street Diner, waiting by the car while his boss ate breakfast with Frank Costello. Frank accompanied Bumpy to Cuba to see Lucky Luciano. “I stayed outside,” Frank remembers, “just another guy with a bulge in my pocket.”

“There was a lot about Bumpy I didn’t understand, a lot I still don’t understand … when he was older, he’d lean over his chessboard in his apartment at the Lenox Terrace, with these Shakespeare books around, listening to soft piano music, Beethoven — or that Henry Mancini record he played over and over, ‘Baby Elephant Walk’ … He’d start talking about philosophy, read me from Tom Paine, ‘The Rights of Man’ … ‘What do you think of that, Frank?’ he’d ask … I’d shrug. What could I say? Best book I remember reading was Harold Robbins’s The Carpetbaggers.”

In the end, as Frank tells it, Bumpy died in his arms: “We were at Wells Restaurant on Lenox Avenue. Billy Daniels, the singer, might have been there. Maybe Cockeye Johnny, J.J., Chickenfoot. There was always a crowd around, wanting to talk to him. Bumpy just started shaking and fell over.”

Three months after Martin Luther King’s assassination, the headline in the Amsterdam News said BUMPY’S DEATH MARKS END OF AN ERA. Bumpy had been the link back to the wild days of people like Madame St. Clair, the French-speaking Queen of Policy, and rackets wizard Casper Holstein, who reportedly aided the careers of Harlem Renaissance writers. Also passing from the scene were characters like Helen Lawrenson, a Vanity Fair editor whose tart account of her concurrent affairs with Condé Nast, Bernard Baruch, and Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson can be found in the long-out-of-print Stranger at the Party.

Lucas says, “There wasn’t gonna be no next Bumpy. Bumpy believed in that share-the-wealth. I was a different sonofabitch. I wanted all the money for myself … Harlem was boring to me then. Numbers, protection, those little pieces of paper flying out of your pocket. I wanted adventure. I wanted to see the world.”

A few days after our Harlem trip, drinking Kirins in a fake Benihana, Frank told me how he came upon what he refers to as his “bold new plan” to smuggle heroin from Southeast Asia to Harlem. It is a thought process Lucas says he often uses when on the verge of a “pattern change.”

First he locks himself in a room, preferably in a hotel in Puerto Rico, shuts off the phone, pulls down the blinds, has his meals delivered, and does not speak to a soul for a couple of weeks. In this meditative isolation, Lucas engages in what he calls “backtracking … I think about everything I done in the past five years, look in each nook and cranny, down to what I put on my toast in the morning.”

Having vetted the past, Lucas begins to “forward-look … peering around every bend in the road ahead.” It is only then, he says, “when you can see back to Alaska and ahead as far as South America … and know nothing, not even the smallest hair on a cockroach’s dick, can stand in your way” — that you are ready to make your next big move.

If he really wanted to become “white-boy rich, Donald Trump rich,” Lucas thought, he’d have to “cut out the guineas.” He’d learned as much working for Bumpy, picking up “packages” from Fat Tony Salerno’s Pleasant Avenue guys, men with names like Joey Farts and Kid Blast: “I needed my own supply. That’s when I decided to go to Southeast Asia. Because the war was on, and people were talking about GIs getting strung out over there. I knew if the shit is good enough to string out GIs, then I can make myself a killing.”

Lucas, traveling alone, had never been to Southeast Asia, but he felt confident. “Because I knew it was a street thing over there. You see, I never went to school even for a day, but I got a Ph.D. in street. When it comes to a street atmosphere, I know I’m going to make out.”

Checked into the Dusit Thani Hotel in Bangkok, Lucas soon hailed a motorcycle taxi to take him to Jack’s American Star Bar, an R&R hangout for black soldiers. Offering ham hocks and collard greens on the first floor and a wide array of hookers and dope connections on the second, the Soul Bar, as Frank calls it, was run by the former U.S. Army sergeant Leslie “Ike” Atkinson, a country boy from Goldsboro, North Carolina, who happened to be married to one of Frank’s cousins, which made him as good as family.

“Ike knew everyone over there, every black guy in the Army, from the cooks on up,” Frank says. It was this “army inside the Army” that would serve as the Country Boys’ international distribution system, moving heroin shipments almost exclusively on military planes routed to Eastern Seaboard bases. Mostly these were draftees and enlisted men, but “there were also generals and colonels, guys with eagles and chickens on the collars, white guys and South Vietnamese too,” Lucas swears. “These were the greediest motherfuckers I ever dealt with. They’d send people out to get their ass shot up but do anything if you gave them enough money,” says Frank who, as part of his scam if need be, would dress up as a lieutenant colonel himself. “You should have seen me — I could really salute.”

Lucas soon located his main overseas connection, an English-speaking, Rolls-Royce-driving Chinese gentleman who went by the sobriquet 007. “I called him 007 because he was a fucking Chinese James Bond.” Double-oh Seven took Lucas upcountry, to the Golden Triangle, the heavily jungled, poppy-growing area where Thailand, Burma, and Laos come together.

“It wasn’t too bad, getting up there,” says Lucas. “We was in trucks, in boats. I might have been on every damn river in the Golden Triangle. When we got up there, you couldn’t believe it. They’ve got fields the size of Tucson, Arizona, with nothing but poppy seeds in them. There’s caves in the mountains so big you could set this building in them, which is where they do the processing … I’d sit there, watch these Chinese paramilitary guys come out of the mist on the green hills. When they saw me, they stopped dead. They’d never seen a black man before.”

Likely dealing with remnants of Chiang Kai-shek’s defeated Kuomintang army, Lucas purchased 132 kilos that first trip. At $4,200 per unit, compared with the $50,000 that Mafia dealers charged Stateside competitors, it would turn out to be an unbelievable bonanza. But the journey was not without problems.

“Right off, guys were stepping on little green snakes, dying on the spot. Then guess what happened? Banditos! Those motherfuckers came right out of the trees. Trying to steal our shit. The guys I was with — 007’s guys — all of them was Bruce Lees. Those sonofabitches were good. They fought like hell.

“I was stuck under a log firing my piece. Guys were dropping. You see a lot of dead shit in there, man, like a month and a half of nightmares. I think I ate a damn dog. I was in bad shape, crazy with fever. Then people were talking about tigers. I figured, that does it. I’m gonna be ripped up by a tiger in this damn jungle. What a fucking epitaph … But we got back alive. Lost half my dope, but I was still alive.”

It is a fabulous cartoon, an image to take its place in the easy-riding annals of the American dope pusher — the Superfly in his Botany 500 sportswear down in the malarial muck, clutching his 100 keys, Sierra Madre-style, bullets whizzing overhead. “It was the most physiological thing I done and hope not to again,” says Lucas.

Throughout it all, Lucas swears, he remained a “100 percent true-blue, red-white-and-blue patriotic American.” Details concerning the dope-in-the-body-bags caper have been wildly misrepresented, he says, stories that he and Ike Atkinson actually stitched the dope inside the body cavities of the dead soldiers being nothing but “sick cop propaganda.”

“No way I’m touching a dead anything. Bet your life on that.”

What really happened, he says, was that he and Ike flew a country-boy North Carolina carpenter over to Bangkok. “We had him make up 28 copies of the government coffins … except we fixed them up with false bottoms, big enough to load up with six, maybe eight kilos … It had to be snug. You couldn’t have shit sliding around. Ike was very smart, because he made sure we used heavy guys’ coffins. He didn’t put them in no skinny guy’s …”

Of the dozens of smuggling operations he ran from Asia, Frank still rates “the Henry Kissinger deal” as an all-time favorite. To hear Frank tell it, he and Ike were desperate to get 125 keys out of town, but there weren’t any “friendly” planes scheduled leaving. “All we had was Kissinger. He was on a mercy mission on account of big cyclones in Bangladesh. We knew a cook on the plane and gave $100,000 to some general to look the other way. I mean, who the fuck is gonna search fucking Henry Kissinger’s plane?

“… Henry Kissinger! Wonder what he’d say if knew he helped smuggle all that dope into the country? … Hoo hahz poot zum dope in my aero-plan? Ha ha ha …”

During the dope-plague days of the late sixties and early seventies, when the Feds (over)estimated that half the country’s heroin addicts were in New York and 75 percent of those in Harlem, the Amsterdam News reported what 116th Street was like during the reign of Frank Lucas. “We’re being destroyed by dope and crime every day,” said Lou Broders, who ran an apparel shop at 253 West 116th Street. “It’s my own people doing it, too. That’s the pity of it. This neighborhood is dying out.”

In the face of such talk, Frank, who recalls the 1967 riots as “no big thing,” exhibits typically willful obliviousness. “It’s not my fault if your television got stolen,” he says. “Besides, Harlem was great then. It wasn’t until they they put me and Nicky Barnes in jail that the city went into default. There was tons of money up in Harlem in 1971, 1972 — if you knew how to get it. Shit, those were the heydays.”

To hear Frank tell it, life as a multimillionaire dope dealer was a whirl of flying to Paris for dinner at Maxim’s, gambling in Vegas with Joe Louis and Sammy Davis Jr., spending $140,000 on a couple of Van Cleef bracelets, and squiring around his beautiful mistress — Billie Mays, step-daughter of Willie, who, according to Lucas, he’d snaked away from Walt “Clyde” Frazier. The grotty 116th Street operation was left in the hands of trusted lieutenants. If problems arose, Lucas says, “we’d have 500 guns in the street in 30 minutes, ready to hit the mattress.”

Frank’s money-laundering routine consisted of throwing duffel bags filled with cash into the back seat of his car and driving to a Chemical Bank on East Tremont Avenue in the Bronx. Most of the money was sent to Cayman Island banks; if Frank needed a little extra, he’d read the newspaper in the lobby while bank managers filled a duffel with crisp $100 bills. For their part in the scheme, Chemical Bank would eventually plead guilty to 200 misdemeanor violations of the Bank Secrecy Act.

As Bumpy had once run the Palmetto Chemical Company, a roach-exterminating concern, Frank opened a string of gas stations and dry cleaners: “I had a dry-cleaning place on Broadway, next to Zabar’s. Once I had to go behind the counter myself. And you know I ain’t no nine-to-five guy. These old ladies kept coming in, shoving these shirts in my face, screaming, ‘Look at this spot’ … I couldn’t take it. I just ran out of the place, didn’t lock up or even take the money out of the cash register.”

Show business was more to Frank’s taste, especially after he and fellow Harlem gangster Zack Robinson began hanging out at Lloyd Price’s Turntable, a nightclub at 52nd Street and Broadway. “There’d be Muhammad Ali, members of the Temptations, James Brown, Berry Gordy, Diana Ross,” says Frank, who calls the Turntable “a good scene — the integration crowd was there, every night.”

In 1970, Price, a Rock and Roll Hall of Famer who’d had huge hits with tunes like “Personality” and “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” decided to make a gangster movie, The Ripoff, set on the streets of New York.

“The idea was to get real, practicing gangsters to play themselves,” Price remembers. “We needed the villain romantic lead, the guy with the sable coat and the hat, so I thought, why not get Frank?”

“It was like Shaft before Shaft,” says Lucas. “All the cars in the picture was mine. We did a scene with me chasing Lloyd, shooting out the window of a Mercedes on the West Side Highway. I put 70, 80 grand into the movie. It was real fun.”

Never finished, the footage missing, The Ripoff qualifies as the Great Lost Film of the blaxploitation genre. “A lot of strange things happened making The Ripoff,” says Lloyd Price. “Once, we went over to the editing room. Frank didn’t like the director. ‘You want to cut, I’ll show you how to cut,’ he said, pulling out his knife. ‘Frank, man,’ I told him, ‘this isn’t the way they do it in the movie business.’ “

A drug kingpin attracts attention from the police, and according to Lucas, most of his trouble came from the NYPD’s infamously corrupt Special Investigations Unit. Known for its near-unlimited authority, the SIU wrote its own mighty chapter in the crazy-street-money days of the early-seventies heroin epidemic; by 1977, 52 out of 70 officers who’d worked in the unit were either in jail or under indictment.

The worst of the SIU crew, Lucas says, was Bob Leuci, the main player in Robert Daley’s best-selling Prince of the City. Says Frank: “We called him Babyface, and he had the balls of a gorilla. He’d wait outside your house and fuck with you.” Once, according to Lucas, Leuci caught him with several keys of heroin and cocaine in his trunk. “This is gonna cost you,” the detective supposedly said after taking Lucas down to the station house. The two men then reportedly engaged in a heated negotiation, Lucas offering 30 grand, Leuci countering with “30 grand and two keys.” Seeing no alternative, Lucas said, “Sold!”

“That’s why I had to move downtown,” wails Frank. “To duck Babyface.”

Lucas likewise expresses no love for his more famous Harlem dope-dealer rival Nicky Barnes, who rankled the older pusher by appearing on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in his trademark gogglelike Gucci glasses, bragging that he was “Mr. Untouchable.” The brazen assertion soon got then-president Jimmy Carter on the telephone demanding that something be done about the Harlem dope trade. “Talk about bringing the heat,” the Country Boy moans.

According to Lucas, it was Barnes’s “delusions of grandeur” that led to a bizarre chance meeting between the two drug lords in the lingerie department of Henri Bendel on 57th Street. “Nicky wanted to make this black-Mafia thing called the Council. An uptown Cosa Nostra. The Five Families of Dope. I didn’t want no part of it. Because before long, everyone’s gonna think they’re Carlo Gambino. That’s trouble.

“Anyway, I’m with my wife at Henri Bendel’s, and who comes up? Nicky fucking Barnes! ‘Frank,’ he’s going, ‘we got to talk … we got to get together on this Council thing.’ I told him forget it, my wife is trying on underwear — can’t we do this some other time? He says, ‘Hey, Frank, I’m short this week, can you front me a couple of keys?’ That’s Nicky.”

Lucas says he thought about quitting “all the time.” His wife, Julie, whom he met on a “backtracking” trip in Puerto Rico, begged him to get out, especially after Brooklyn dope king Frank Matthews jumped bail in 1973, never to be heard from again. “Some say he’s dead, but I know he’s living in Africa, like a king, with all the fucking money in the world,” Lucas sighs. “Probably I should have stayed in Colombia. Always liked Colombia. But I had my heart set on getting a jet plane … there was always something.”

For Lucas, the inevitable came on January 28, 1975, when an NYPD/DEA strike force, acting on a tip from two Pleasant Avenue guys, staged a surprise raid on his house in a leafy neighborhood of Teaneck, New Jersey. In the ensuing panic, Julie Lucas, screaming “Take it all, take it all,” tossed several suitcases out the window. The cases were found to contain $584,000 in the rumpled bills Lucas refers to as “shit street money.” Also found were keys to Lucas’s Cayman Islands safe-deposit boxes, property deeds, and a ticket to a United Nations ball, compliments of the ambassador of Honduras.

“Those motherfuckers just came in,” Lucas says now, sitting in a car across the street from the split-level house where he played pickup games with members of the Knicks. For years, he has contended that the cops took a lot more than $585,000 from him. “Five hundred eighty-five thousand, what’s that? Shit. In Vegas, I’d lose 500 G’s playing baccarat with a green-headed whore in half an hour.” According to Lucas, agents took something on the order of “9 to 10 million dollars” from him that fateful evening. To bolster his claim, he cites passing a federally administered polygraph test on the matter. A DEA agent on the scene that night, noting that “$10 million in crumpled $20 bills isn’t something you just stick in your pocket,” vigorously denies Lucas’s charge.

Whatever. Frank doesn’t expect to see his money again: “It’s just too fucking old — old and gone.”

A few days later, I brought Lucas a copy of his newspaper-clip file, detailing the Country Boy’s long and tortuous interface with the criminal-justice system, a period in which he would do time in nearly a dozen state and federal joints. Lucas silently thumbed through dog-eared headlines like COUNTRY BOYS, CALLED NO. 1 HEROIN GANG IS BUSTED; 30 COUNTRY BOYS INDICTED IN $50M HEROIN OPERATION. There was also an October 25, 1979, Post story entitled CONVICT LIVES IT UP WITH SEX AND DRUGS, quoting a Metropolitan Correctional Center prisoner named “Nick,” convicted killer of five, whining that Lucas had ordered prostitutes up to his cell and was “so indiscreet about it I had to have my wife turn the other way … he didn’t give one damn about anyone else’s feelings.”

One clip, however, did engage Frank’s attention. Titled EX-ASSISTANT PROSECUTOR FOR HOGAN SHOT TO DEATH IN VILLAGE AMBUSH, the November 5, 1977, Times story tells how Gino E. Gallina, then a Pelham Manor mouthpiece for “top drug dealers and organized-crime figures,” was rubbed out “mob style … as many passersby looked on in horror” one nippy evening at the corner of Carmine and Varick Streets.

Lucas reckons he must have spent “millions” on high-priced criminal lawyers through the early eighties. Gino Gallina, however, was the only lawyer Lucas ever physically assaulted, the incident occurring in the visiting room of the Rikers Island prison. Lucas had reputedly given Gallina a large payoff to fix a case, $200,000 of which became “lost.” Upon hearing this, Lucas, said the Daily News, “leaped across the table in the visitors’ pen and began punching Gallina savagely.”

Acknowledging that he told Gallina “if I didn’t get my money in 24 hours he was a dead man” and asserting that the lawyer “did not deserve to live,” Frank still steadfastly maintains he has “no idea at all” about who murdered Gallina.

What Lucas will absolutely not talk about is how he got out of jail, the stuff described in clips like a Newark Star-Ledger piece from 1983 entitled ‘HELPFUL’ DRUG KINGPIN GRANTED REDUCED TERM, in which Judge Leonard Ronco of Newark is reported as cutting in half Lucas’s 30-year New Jersey stretch. This followed the previous decision by U.S. District Court judge Irving Ben Cooper, who “granted the unusual request of Dominic Amorosa, chief of the Southern District Organized Crime Strike Force, to reduce Lucas’s 40-year New York prison sentence to time already served.”

“I ask two things,” Lucas demanded in our first meeting. “One, if they are slamming bamboo rods beneath your fingernails with ball-peen hammers, do not reveal where you saw me; and two, none of that bullshit about being buddy-buddy with the cops. That is out … ” Then, so there was no mistake, he added, “Don’t cross me on this, because I am a busy man and have no time, no time whatsoever, to go to your funeral.”

Still, it was hard to let it go. How was I supposed to explain how he wound up serving less than nine years? To this, Frank replied: “I know I have that mark on me. I was always playing games with them. Go back and look — I never, ever testified against anyone in court. Not once.”

Then finally, Frank said, “Look, all you got to know is that I am sitting here talking to you right now. Walking and talking — when I could have, should have, been dead and buried a hundred times. And you know why that is?

“Because: People like me. People like the fuck out of me.” This was his primary survival skill, said the former dope king: his downright friendliness, his upbeat demeanor. “All the way back to when I was a boy, people have always liked me. I’ve always counted on that.”

That much was apparent when I went to the Eastern District federal court to see Judge Sterling Johnson, the former narcotics prosecutor instrumental in putting the Country Boy behind bars.

Frank told me to look up Johnson, whom he calls “Idi Amin.” “Judge Johnson likes me a lot. You’ll see,” he said.

Johnson greeted me with a burnished dignity befitting a highly respected public official. “This is Judge Johnson,” he said. When I mentioned the name Frank Lucas, Johnson became notably more familiar. “Frank Lucas? Is that mother still living?!” A few days later, chatting in his stately chambers, the judge told me to call Lucas up.

“Get that old gangster on the phone,” Johnson demanded, turning on the speaker.

Lucas answered with his usual growl. “This is Frank. Who’s this?”

Johnson mentioned a name, someone apparently dead, likely snuffed by a Country Boy or two. This got Lucas’s attention. “What? Who gave you this number?”

“Top!”

“Top who?”

“Red Top!” Johnson said, invoking the name of Lucas’s beloved chief dope cutter.

“Red Top don’t got my number …” It was around then that Frank figured it out.

“Judge Johnson! You dog! You still got that stick?” Johnson reached under his desk, pulled out a beat cop’s nightstick, and slapped it into his open palm loud enough for Lucas to hear it. “Better believe it, Frank!”

“Stop that! You’re making me nervous, Judge Johnson!” Lucas exclaimed before gingerly inquiring, “Hey, Judge, they ever get anyone in that Gallina thing?”

Johnson laughed and said, “Oh, Frank. You know you did it.”

Smiling through Lucas’s denials, Johnson said, “Well, come down and see me. I’m about the only fly in the buttermilk down here.”

After he hung up, Johnson chortled, “That Frank. He’s a pisser.”

“You know, when we were first investigating him, the FBI, DEA, they didn’t think he could pull off that Southeast Asia stuff. They wouldn’t let themselves believe an uneducated black man could come up with such a sophisticated smuggling operation. In his sick way, he really did something.”

The memory clearly tickled Johnson, who quickly added, “Look, don’t get me wrong: Frank was as bad as they come. You should never forget who these people really are. But what are you going to do? The guy was a pisser. A pisser and a killer. Easy to like. A lot of those guys were like that. It is an old problem.”

A couple of days later, eating at a T.G.I. Friday’s, Lucas scowled through glareproof glass to the suburban strip beyond. “Look at this shit,” he said. A giant Home Depot down the road especially bugged him. Bumpy Johnson himself couldn’t have collected protection from a damn Home Depot, he said with disgust. “What would Bumpy do? Go in and ask to see the assistant manager? Place is so big, you get lost past the bathroom sinks. But that’s the way it is now. You can’t find the heart of anything to stick the knife into.”

Then Frank turned to me and asked, “You gonna make me out to be the devil, or what? Am I going to Heaven or hell?”

As far as Frank was concerned, his place in the hereafter was assured after he joined the Catholic Church while imprisoned at Elmira. “The priest there was getting crooks early parole, so I signed up,” he says. As backup, Frank was also a Baptist. “I have praised the Lord,” he says. “Praised Him in the street and praised Him in the joint. I know I’m forgiven, that I’m going to the good place, not the bad.”

But what did I think? How did I see it going for the Country Boy beyond this world? It was a vexing question, as Sterling Johnson said. Who knew about these things? Frank was a con man, one of the best. He’d been telling white people, cops and everyone else, pretty much what they wanted to hear for decades, so why should I be different? It was true: I liked him. I liked the fuck out of him. Especially when he called his 90-year-old church-lady Hulk Hogan-fan mother, which he did about five times a day. But that wasn’t the point.

Braggart, trickster, and fibber along with everything else, Lucas was nonetheless a living, breathing historical figure, a highly specialized font of secret knowledge, more exotic, and certainly less picked over, than any Don Corleone. He was a whole season of the black Sopranos — old-school division. The idea that a backwoods boy could maneuver himself into position to tell at least a plausible lie about stashing 125 kilos of zum dope on Henry Kissinger’s plane — much less actually do it — mitigated a multitude of sins.

In the end, even Lucas’s resounding lack of repentance didn’t seem to matter. About the only flicker of remorse I’d seen from him occurred following a couple of beers we had with one of his brothers, Vernon Lee, who is known as Shorty.

A bespectacled man now in his early fifties, Shorty followed Frank to Harlem in 1965. “We came up from Carolina in a beat-up car, the brothers and sisters, Mom and Dad, with everything we owned, like the Beverly Hillbillies.” From the start, Shorty knew what he wanted. “Diamond rings, cars, women. But mostly it was the glory. Isn’t that what most men really dream of? The glory.”

Then Shorty reached across the table and touched Frank’s hand. “We did make a little bit of noise, didn’t we?” Shorty said. To which Frank replied, “A little bit.”

Later, sitting in the car, Frank watched his brother make his way across the frozen puddles in the late-afternoon light and sighed. “You know, if I’d been a preacher, they would have been preachers. If I’d been a cop, they’d have been cops. But I was a dope dealer, so they became dope dealers … I don’t know … if I’d done right.”

After a while, Frank and I stopped in for another beer. The surroundings were not plush. Frank said, “Shit … from King of the Hill to dumps like this.”

The Knicks game was over, so we sat around for a few hours watching The Black Rose, an old sword-fight movie with Tyrone Power and Orson Welles. Welles is a favorite of Lucas’s, “at least before he got too fat.” Then, when it was time for me to go, Lucas insisted I call him when I got back to New York. It was late, rainy, and a long drive. Frank said he was worried about me. So, back in the city, driving down the FDR, by the 116th Street exit, I called Lucas up, as arranged.

“You’re back, that’s good,” the Country Boy croaked into the phone. “Watch out. I don’t care what Giuliani says, New York is not so safe. You never know what you might find out there.” Then Frank laughed that same chilling haint of a laugh, spilling out the car windows and onto the city streets beyond.