Losing friends and family, seeing the horror of the World Trade Center disaster firsthand, changed lives in myriad, unpredictable ways. Here are 15 personal stories.

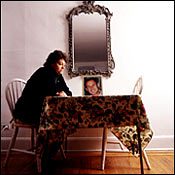

Mary Maciejewski

A clerical worker, Maciejewski, 41, lost her husband, a waiter at Windows on the World.

Jan’s normal shift was lunch, so he’d get there at 10:30 a.m. But the Friday before, his manager called and asked if he could work breakfast. My office is about ten blocks away on Water Street. The minute I got to my desk – I work on the forty-sixth floor – people were screaming and running to the windows. Then my phone rang, and it was Jan. He told me that there was smoke, awful smoke, and that they were in touch with the Fire Department, who told them not to move, that they were going to come and get them. I told him to go wet a napkin and put it over his face so he could breathe. He told me there was no water anywhere so he was going to go get some from the flower vases. Then at that point, the second building was hit, and they decided to evacuate my building. Jan told me to hang up and get out, so I would be safe, and to call him back on his cell phone when I got outside. But there was no connection.

Jan wanted kids right away. I kept saying, “Let’s wait till we can afford a house.” Now I really regret it. I see mothers with their children and I think, I’m never going to hear somebody call me Mommy, and Jan never had the opportunity to have someone call him Daddy. I meet once a week with a group of women who lost their husbands at the World Trade Center. It’s what gets me through the days. There are two of them who have children, and I tell them how lucky they are because they have a part of their husbands left.

Every day, the subway I take passes under the Trade Center, and I’ll talk to him or say a prayer. I can’t bring myself to go to the site, so this is my way of being there.

In the beginning, I slept at my sister’s, on one of those blow-up mattresses. I just couldn’t go back to the apartment. Jan had an identical twin and he lives upstairs, and seeing him was excruciating. Now I’m home, and Jan is everywhere. But I need that. I have his shirt that he wore the day before and the shorts that he wore around the house. And on one hanger I have about ten of his shirts and I’ll just take the hanger out and hug it. They haven’t found Jan. And I don’t want them to find him, because my biggest fear is that he suffered. I’d rather think that it happened fast and that he was in the air when the buildings fell. I dread that the doorbell will ring and they’ll tell me, “We found the remains of your husband.”

– LISA DEPAULO

Jessica Trant

A 19-year-old freshman at Pace University from Northport, New York, Trant lost her father, Daniel, a bond trader at Cantor Fitzgerald.

I was waiting for my business-law class to start when two of my friends told me about the World Trade Center. I got up and ran to my room. My phone was ringing; it was my mom. She was like, “Daddy called. He said he was gonna make it out; everything’s gonna be all right.” She called a Town Car for me. I came home to see my brother, Daniel, curled up in a ball, crying. Then my mom told me what my dad had really said: that a plane had hit the building, there was fire everywhere, the smoke was unbearable, and he probably wasn’t going to make it but he was going to try. And that he loved her and he loved the children, and to take care of the children for him.

March 2 would have been the thirteenth anniversary of the day my dad adopted me. That was a day he always had just for us. My mom took me shopping and we went to dinner. I had this really weird dream. My dad called me on the phone saying that he forgot who he was, but he finally remembered and he made it out. He’s like, “I made it home for our anniversary.” And then he’s like, “I gotta go now.” And I started crying and I was like, “Don’t go, Dad!”

My mom is having the roughest time; they were so in love. That’s the hardest part for me. Not a day goes by that she doesn’t cry to me on the phone. Sometimes she looks like she’s wasting away; she has to drink Ensure.

I told my friends they can ask any question they want. They asked what it’s like not having his body. There’s nothing left of him; there’s nothing left to bury. It’s just not a way to go. I know they’ve found body parts, like bones, from some people. I sure don’t want that; I want my father, so I can go somewhere and have my own time with him.

–ETHAN SMITH

Chuck Platz

An investment banker, Platz, 24, needed to find a new roommate after his friend Welles Crowther died.

Welles was always out the door early. He was an equities trader at Sandler O’Neill. We met in ‘98 in Madrid – partners on an internship, learning how the international markets worked. We hung out all day at work and had sangria and cigars at night. We’d talk about how Spanish women were the most beautiful in the world.

After I graduated and came to New York, we agreed to share an apartment in the West Village. Welles said it was perfect, it was No. 19 – he said that was his lucky number, his lacrosse number. Living with Welles was an honor. It was always an adventure. He’d burst into my room and say, “Come on, we’re going out!”

His room was untouched for the longest time. His glass of water was still on his dresser. Not that I was scared – it was just that maybe I was nervous it would set in that he wasn’t coming back. I looked and looked for someone. The problem I ran into was that people were worried about their jobs and not sure about moving into a room in a $2,600 apartment. Welles’s family tried to help.I met Kara in December. She was supposed to move out of New York to get married, but the night before leaving, her boyfriend called the wedding off. So she moved in.

The apartment’s pretty different now. Kara brought in the Speed Racer poster, the lamp, the leopard chair, and the cat. But everything else looks the same. The aquarium was Welles’s. It’s in pretty bad shape. We bought pH test kits but we couldn’t keep a fish alive for more than three weeks.

I was really nervous about living with someone I didn’t know well. I told Kara I was really lucky, because living with her was a nonadjustment. She smiled and gave me a hug.

– ROBERT KOLKER

Dr. Robert Klitzman

An author and assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, Klitzman lost a sister who worked at Cantor Fitzgerald.

I got a call from my mother at ten to nine as I was walking to a meeting. Even though my sister Karen worked at Cantor Fitzgerald, I thought the odds were good that she’d be okay. But then I passed a security guard who was watching TV. There were torrents of black smoke coming from the World Trade Center. I thought, Are we going to have to set up a memorial? Are we going to have to sit shivah?

Sitting down for bagels and coffee at the meeting, I felt like I was already sitting shivah. We didn’t have the meeting, of course; the entire psych department, almost 300 of us, watched TV. When the towers fell, there was utter silence. I was the only one at the time who knew someone there, and the rest of my family, my mother and Karen’s twin sister, Donna, were stuck outside of Manhattan, so it was a lonely feeling.

I called St. Vincent’s and said, “I’m a physician, and my sister worked in the World Trade Center.” They said, “If you’re coming down to look for your sister, don’t bother. We’re mobbed with families. But if you want to come as a physician, we could use you.” I went anyway and offered my services. Then a doctor, covered in soot, burst into the hospital. He said that everyone had been vaporized. I thought, How do I tell my mother that my sister has been vaporized? The memorial was scheduled for the following Sunday and it went well, even though I was so nauseous that I’d shared a bottle of Extra Strength Tylenol with the cantor and my sister Sue in the elevator.

It’s been very difficult for the families of people who worked in the Trade Centers. The press focuses on the cops and firefighters, but you don’t hear much about families like ours. The groups representing the families seem very ad hoc, so I don’t feel like there’s a real sense of community there. But I don’t feel like I need a support group; I’m suddenly talking to everyone in my family once a day, which didn’t happen before. And I’ve reestablished a lot of friendships. But I don’t feel a sense of closure – there’s no body, there’s no grave site. Every step – disconnecting her phone, turning the cable TV off, packing up her books, cleaning out her bathroom – hammers another nail into the coffin. But there isn’t one.

– ETHAN BROWN

Karin Batten

Batten, 54, is an artist who had a studio on the ninety-first floor of Tower One.

I got a grant from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council to paint for four months, from June to October. I’ve done aerial views – paintings of New York – since the late eighties, so I was so happy to get this grant. But I’ll tell you, every time I went up there on the elevators, it was always in my mind that if anything happened there was no way you could get out.

That morning, I’d gotten my son off to school – I.S. 89, by the World Trade Center – and decided I’d better go vote at Westbeth, where I live. The voting went so slowly, and when I was finishing up, we started hearing sirens going by. Once I found out what happened, I knew I had to go get my son. Luckily, I found him, and all the kids told me they saw the plane coming by their classroom and hitting the tower and they saw people jumping from the building. Then we all turned around and Tower One – where all my work, my supplies, everything, was – was coming down. Several children whose parents worked at the World Trade Center just screamed.

I was in shock for six weeks, I couldn’t do anything. An artist I was supposed to meet up there walked down ninety-one floors and made it, but she’s never been the same, she’s in bad shape.

A friend of mine convinced me, because the air quality was so bad and my family is young, that it made sense for us to leave for the weekends at least, and so every weekend I went away until shortly before Christmas.

At the end of November, I knew I had to really force myself to do something, that if I went back to painting it would make me feel better. I started painting views from my studio at the World Trade Center, from photographs and from memory. I thought that’s maybe how I would get the sadness and the fear out of my system. But sometimes I just stand there and start crying.

– ARIC CHEN

Andrea Refol

The owner of a vintage-clothing store in Park Slope, Refol started having contractions when she saw the second plane hit.

It was our 4-year-old Jordan’s first day of pre-kindergarten. We left our house at 8:22 a.m.; I was on my way to a doctor’s appointment, the radio was on, and we heard the news report. I had my first contraction. We were driving down Sackett Street in Brooklyn, and we watched the second plane make contact. My first thought was, Oh, my God, my appointment – I’m supposed to have a baby!

We went home. I was going nuts. I told myself this is just one baby, one child, compared with the worst thing to happen in American history. But it was my baby. My doctor called from New Jersey and told me he could get in the next day and that I should get to the hospital any way I could.

I didn’t sleep that night, because I was having contractions. The next morning, they really started coming. We left Jordan with a friend because they’d canceled school. There were roadblocks everywhere. At the Manhattan Bridge I said to this cop, “I’m in labor! I’ve got to get to the hospital!” He said, “Are you sure?” I said, “I’m pretty sure.” As we were going over the bridge, there was smoke coming up so you couldn’t see lower Manhattan. My husband asked, “Are you crying because you’re in pain?” I said, “No. I’m crying because they fucking blew up my city.” When we got to the hospital, people were starting to post pictures. My blood pressure skyrocketed so my doctor said, “Let’s do this now – in an hour, my team may not be available. Let’s get this show on the road.” They did a C-section.

We sent an e-mail around to say Griffin was born, but it was hard to show joy or elation – the term we used was hope. Hope seemed right.

Six months after, it’s almost unimaginable to me that the shadow of this event will ever dissipate. I am thinking more globally than I ever have before. I don’t remember thumbing through the paper in the same way when Jordan was a baby. When she was born, I was focused on just her; I was fully absorbed in her care and well being. Now that Bloomberg and Pataki are talking about possible threats to the city, I am very fearful for my children.

– ARIEL LEVY

Ada Rosario Dolch

Principal of the High School for Leadership and Public Service on Trinity Place, Dolch lost her sister Wendy, who worked for Cantor Fitzgerald.

I was about to head over to the World Trade Center to buy a battery for my watch when the first plane hit. I was in the lobby, which became an instantaneous command center, trying to make decisions, with no real understanding of what was going on, trying to create a sense of calm, with hordes of people running in looking for safety.

We had 500 kids upstairs, our teachers, our cooking staff, and our security officers. I remember I said a prayer because my sister was there, but I didn’t think about her again until I got home at 4:30 p.m. I just couldn’t, because if I’d stopped, I wouldn’t have been able to concentrate on my kids.

After the second plane hit, there was an interlude – I realize now it was only 40 minutes, but it seemed like hours – we were planning, thinking, wondering: Where do we go? How do we move them out? What do we do about our girl in a wheelchair? Our girl who’s blind? Our girl who’s just had heart surgery?

We made it to Battery Park. As we were entering, the buildings collapsed. Some people remember a roar; I remember a snapping, must have been those girders, just in my face, loud. I see the tsunami wave, as tall as those buildings. The black cloud came, we sucked in that stuff, then it became gray and then this white snow.

We planted bulbs in the park, and it’s very therapeutic to go back there because that was our refuge. We spent four and a half months at the High School of Fashion Industries, and that was a very difficult journey. It wasn’t our home. Every day that we couldn’t return created a greater loss. All the gifts and therapy in the world weren’t helping us move ahead. Moving ahead meant that we had to go home.

The kids are phenomenal. They wanted to come back to school – because we all experienced this together. Their families at home weren’t ready. I keep saying, “We’re moving forward.” That’s my mantra. I tell them, “You are history-makers. People will look to you and ask you to tell the story.” And I tell them, “If you fall apart, you will never be able to help this world be rebuilt.”Are we moving ahead quickly? No. We have lost a lot of the academic year. Will we be able to recover? Yes. Just not right now.

– LOGAN HILL

David Fitzpatrick

The most senior member of the NYPD’s Technical Assistance Response Unit, Fitzpatrick photographed the burning towers from a police helicopter.

I went up in a copter just after the second plane hit. As soon as a chopper would land for fuel, I would jump in another one.

We couldn’t believe what we were seeing. Our pilot had heard that there were two more jumbo jets unaccounted for and that we should be on the lookout, so our eyes were peeled in all directions, looking at the Statue of Liberty and the Empire State Building, waiting for another plane. The copter we had was incapable of rescue, but we didn’t see anyone on the rooftops at all. When the first tower came down, it was just horrible; we were just above the building, and we felt so helpless.

I spent eighteen days documenting ground zero, and not a day goes by when I don’t relive it. One strange thing: I was in the cemetery near Trinity Church, and I took a picture to show the relationship between the church and the World Trade Center. Two weeks later, I picked up my loop and looked at it. I saw that in the back of one of the tombstones there’s an American flag sitting in the dirt. And there’s something about the tombstone, either a crack or some dirt, that makes it look like a silhouette of George Washington’s face looking at the flag. I showed it to people, and even without my saying anything, they say that’s what it looks like. It was like a positive thing, you know?

I still go down to Zero periodically now just to do aerial and ground photos. There’s still a sense of camaraderie there – police and firefighters, of course, but also the construction workers and volunteer workers. But the site, it’s never lost its feeling of devastation. Even though I go there so often. That never goes away.

–ROBERT KOLKER

Richard “Flash” Polatchek

President of the options-trading firm Heights Partners, Polatchek works on the floor of the American Exchange and, until September 11, lived on the thirty-fourth floor of Gateway Plaza in Battery Park City.

I had just flown back from Italy on September 10 and was still jet-lagged. When the first plane hit, I was in the shower. I pulled on some jeans and rushed out onto my terrace, which looked right out over the Trade Center. Then I heard this terrible roar, just over my right shoulder. The plane was so close I could read the BOEING 767 painted under the cockpit window. Then all of a sudden, the pilot cut the engines. That’s what no one talks about. He just glided in for the last couple hundred yards. There was this weird, horrible silence right before that plane hit.

I ran outside, just in my jeans – no shirt, no shoes, no wallet, no keys. That’s when I saw all these firemen come running out of Tower Two, screaming to get away, the building was imploding. When the building came down, it wasn’t a “cloud of dust,” it was just this wave of debris – concrete, wire. It was knocking people off their feet.

There was a fireboat docked next to the promenade, so I just jumped onto the deck. Some people near me were jumping into the river. By that point, though, other boats were coming in, sending out these really big wakes, throwing our boat up against the promenade. I’ll never forget, I looked down right next to the boat and saw this one woman, maybe 45, wearing business clothes. She had jumped into the river, and she just vanished.

I’ve been renting in SoHo, and now I’m looking to buy there. It’s a real neighborhood, with the restaurants and the shops. It’s very emotional to try to go back home now; I don’t want to be in that space anymore. They’ve done so much cleanup work there in the last few months, it looks like a parking lot now. To me, it’s like looking out at a graveyard. My ex-wife and daughter still live in the area, but if I do anything more than go down and pick up my daughter, it brings that whole day back. I just don’t need that.

Going to work is better now. It’s still emotional, but I don’t know, when you’re at work, it’s like you block a lot of it out. Business is back; last month was one of the best months we’ve ever had. For a long time, we were pissed off about the tourists who came down. Why do people bring children down here? I guess you used to come to New York, you’d look out the top of the Trade Center. Now you come to look at what was there.

–ALEX WILLIAMS

Inez Holderness

The beverage director at Windows on the World, Holderness, 24, was out of town on September 11.

When I left work on Tuesday, September 4, I had cleaned the office and given everyone my phone numbers and a “what to do” list in case anything went wrong while I was in North Carolina for my sister’s wedding. The previous week, I had just promoted Steve Adams, one of our assistant cellar masters, to beverage manager, so I was also nervous about leaving him, since he was so new to the job.

I woke up at 9 a.m. on Tuesday, the 11th, to find my mother standing over me and crying. I am very blessed not to have been there, and I’m blessed that Stephen, my boyfriend and the restaurant’s sommelier, wasn’t due in to work until noon. He doesn’t like to talk about it; I could talk about it every minute of the day, but only to him.

I miss Windows so much. I miss the people and the 63-second elevator ride to the top and the cafeteria and my desk. Stephen and I were convinced that if we got back into the swing of things, we would return to normal. It was obviously the wrong approach. Stephen often has nightmares, and I cry more than I talk. I found another job as a beverage manager in midtown, but going to work is a chore now, and I have trouble finishing anything I start. We have finally decided it’s time to leave New York. We both feel like we have to. I want to be near my family. Then we’re going to France to pick grapes.

Stephen and I got engaged. It’s so helpful having the closest person to me understand my feelings of the past six months. My parents are concerned that the foundation of our relationship is this tragedy, but I know that we love the same things and have the same ethics.

– BETH LANDMAN KEIL

Dr. Jeffrey Burkes

Burkes is the chief dental consultant to the office of chief medical examiner.

You always have to have a “what if” mentality. For years, we always talked about “What if a jumbo jet hit another jumbo jet?” We were thinking 500 people; that’s what we prepared for. So far we’ve issued over 740 death certificates; more than 460 were dental I.D.’s. The tooth is the body structure that’s most resistant to pressure, fire, heat. We still don’t have a complete set of antemortem records for each victim, though. It’s the families. A lot of people are in denial. They don’t want to say, “Well, let’s get the dental records, he’s probably dead.”

The biggest problem I had was that people would want to work eighteen-hour days, come back in, and get burnt out. It sucked you in like a black hole. One guy’s wife called and was very upset; she hadn’t seen him in two days. I had to put the guy in a car and drive him home myself.

Now it’s more routine, less frantic. Four or five dentists at a time, seven days a week from 7 a.m. to about 8 p.m. Around Christmas, one of my daughters wrote me a note saying, “We miss you, we want you to come home, but we know what you’re doing is important.” I missed their basketball and softball games, but I made it to the final cheerleading competition.

Other parts of the country think we’re okay. But we’re not okay. It’s taken its toll on me. My income is down for the first time ever because I’m not in my office. I’m sure I lost patients who couldn’t wait.

But I don’t want any relative ever thinking, Well, it’s not his sister, what does he care? I would like to see everybody identified. The United States is a country of law; we have to settle estates, probate wills, and we need a positive identification to do that. I’m still shooting for 100 percent. We’re not down to the bottom yet. I don’t assume that anybody was so badly burnt, vaporized, that we’re not going to find remains. If someone disagrees, I would like to know what they base their opinions on, because I know of no other jurisdiction where two 110-story buildings, an acre apiece, collapsed. It’s never happened. This is something very special.

– SARAH BERNARD

John Maguire

A 28-year-old finance associate with Goldman Sachs, he helped carry Father Mychal Judge.

I served as a tank officer in the Army after graduating from West Point in 1995. From my office at Goldman Sachs, I learned pretty quickly what was happening, and I wasn’t going to sit and watch as my country was being attacked.

I made my way up to City Hall Park when the south tower crashed down. At the escalators at the WTC, I saw the firemen carrying a man I later discovered was Father Mychal Judge in a chair. I offered them a hand. It took five men because the ground was shifting on top of the debris, which made it difficult to walk. We carried him to a street corner and laid his body on the sidewalk. I pushed on his chest with a thought of starting CPR. No response. We folded his hands and covered his face with a jacket.

I went back and helped evacuate another man, with blood coming from his ears. Then I heard a huge roar. My Army instinct took over and I dove for cover under a truck. With all the material bearing down on me, I thought I was going to die. I saw an injured guy on the ground, and with a firefighter who had a headlamp, we dragged him to an office building. I took his dentures out, cleared his mouth of ash, and helped him into an ambulance.

I had problems breathing weeks after it happened, and in the first few weeks it was hard to focus. I didn’t talk to any professionals; I decided to go the informal route, to talk to people who I knew and who knew me. Are things more difficult now? Yes. My commute is longer, and life seems a little more stressful. But that is a small price to pay in light of what others lost.

I find it hard to relax. The source of the stress is not something you can put your finger on now. Seeing fire trucks racing down the street, when the plane crashed at JFK – those things brought it back right when I thought I was getting over it.

I think my way of dealing with it was just getting back to work. When you have too much time to think, that is when it overwhelms you. I’ve had nightmares, and I have not been able to throw away the clothes I wore that day. If I have children some day, I want to be able to show them the torn clothes.

– JONATHAN KAPLAN

Christine Bennett

Bennett’s fiancé, Danny Rosetti, was installing office furniture at AON on the 105th floor of Tower Two.

We met at Scores five years ago. I was a bartender. He was a regular. We were going to get married, but the baby came along first.

He got into the carpenters union in April. He was happy, finally. They happened to send him to the Trade Center for two days. Monday he came home and he was so excited … “You can’t believe, Chris, you’re so high up,” he said. “The clouds are, like, below you.” He actually said he felt like he was close to heaven. And then, uh, Tuesday … He always said he wasn’t going to live past 35. He was 32.

I ended up going in to ground zero that night. His brother-in-law was a police officer in Jersey. I wish I hadn’t. Every day I can still smell the fire, the smoke, I can still hear the sirens and the rescue workers, like I just walked away from it.

We got all of him back. I tried so hard, but they wouldn’t let me see him. There was so much damage they were iffy on the identification. The clothes they sent him back with weren’t his. And of course, I was like, “It’s not him.”

About a week after the wake, I got up and I just hated the whole world. Especially because of the baby. Mad because he doesn’t have a father now, and his father couldn’t wait to take him fishing and get him on the little kid’s softball team. Justin’s so young, he had no idea. Every day I show him the picture and say, “Where’s Daddy?” And he points and kisses it.

Once a week, I can get through a whole day without crying. I can fall asleep now, but it’s still an everyday struggle to get up. But I’m a single mom now. I have to.

I haven’t touched any of his things yet. His dresser still has all his clothes in it. I don’t want to move anything right now. I’m still on the same side of the bed.

I know I’m young and everyone tells me I’m going to have to start dating. But I couldn’t even imagine dating. I mean, I was spending the rest of my life with him. He was the rest of my life.

– JADA YUAN

Amy Ting

An actress who had just finished her first film, Miss Wonton, Ting was working at the Marriott World Trade Center.

I was sitting at the concierge desk in the lobby, on the first floor, when I heard a noise like a piano crash, then saw pieces of building come flying down onto the street; they looked like meteorites. I helped answer the phones; guests were calling from upstairs, you couldn’t see what was going on, the fire alarm was ringing. By the time the guests were evacuated, the lobby was filled with firemen; I was trying to pass them water from the bar. Then one of the fireman came running in through the revolving door, yelling, “The building’s coming down!” And it did; I flew from the middle of the lobby to the corner. It lifted me up in the air. I couldn’t see; all I could hear were things crashing – it was like death had just passed you by. My manager, who was ten feet away from me, didn’t get out; debris fell on top of him.

To get out, we climbed up stories of debris and fallen beams; it was like hiking up a mountain of metal pieces. My shoes were caught, so I was in bare feet, I was bleeding, my whole body was Jello. Climbing down was another obstacle – a fireman fell and dropped into this black hole. When we got out, we couldn’t breathe, it was a ghost town, everything was white.

I spent the night on Staten Island, where one of my colleagues fed me and bathed me, and I called my mom and said, “I can’t believe I got out, I almost died, I love you, I love you.” Afterward, I was scared to come out of my house in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and had nightmares every night, and loud noises made my heart jump.

In mid-November, I went back to New York and was passing through Times Square when I saw the recruiting office for the United States Air Force. Before the 11th, I would never have thought about going into the military – that would be crazy – but my perspective changed. Now it’s reality. I wondered what I was going to become. What my goals were. Now I know I want to get into medicine and help the armed forces. Last week, I finished basic training in San Antonio, Texas. I did obstacle courses and mental- and physical-endurance tests.

My mom didn’t want me to enlist; she wants me to go to college in Europe. But this is what I want to do. When I tell people I’m working for the Air Force, that’s the proudest thing I can say.

– BEN KAPLAN

Jamie Gelormino

A 16-year-old high-school student in Long Island, Gelormino lost her stepfather, FDNY Lieutenant Geoffrey Guja. He was running toward the World Trade Center when it collapsed.

Nothing’s the same. Nothing. Not even sitting here eating dinner is the same. He was a fireman, and all firemen are crazy – they do nothing normal. Wherever we’d go, we’d always be the family that stuck out, the loudest, the ones that got noticed. Now we’re the same as every other family and the world is so much quieter now.

I don’t really talk to my friends about it. I was the only one in my school who had a close family member in there. One time in December, we were talking about it in my English class, and some kid said to me, “Don’t you think you should be over it by now?” He wasn’t affected by it whatsoever. I said, “That makes me so mad, because my father was jumping in there for people like you.”

For a while, when I went to sleep, I would cry every night. I felt so guilty, you know? I felt like he didn’t know that I loved him. I thought I didn’t appreciate him, and that he died thinking I don’t love him. There’s no way for me now to let him know how much I really did.

Four years ago, while he was already a firefighter, he became an R.N. I remember how hard he was studying in the dining room. Geoff’s birthday was two days ago. It was snowing. Me and my sister and my mom went to the cemetery for a little while. We sang “Happy Birthday” and we talked to him and we let balloons go in the air. The headstone just got put in this week. It says WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD.

It has definitely gotten harder. The other day, I was wondering if I’d ever forget what he looked like. I was passing the Manhattan skyline and trying to picture him in my head. I won’t forget what he looks like or his voice. I won’t forget any of that. I can’t.

– ETHAN SMITH