If I hadn’t been looking for J., I’d never have noticed him – neither short nor tall, rail-thin, dark T-shirt and khakis, no logos or name brands. The non-look is by design. “It’s always good to hide in plain sight,” he says. He is a survivalist, but not a grizzled Vietnam vet with a camouflage wardrobe, hunkered in an earth-covered shack in Idaho with a thumb-worn copy of The Poor Man’s Atomic Bomb. He is young, 27, and a freelance artist (album covers, graphic design), and, most discordantly, he lives in New York City, which, all things considered, seems like the last place in the world right now where a survivalist would choose to survive.

At a quiet spot under a tree in Union Square Park, away from the crowds, J. admits that he’s thought about leaving, especially since last September. But he’s become such a student of blending in that sometimes it’s easy for him to consider himself invulnerable, in the city but not of it. That said, he still isn’t sure talking to me is a good idea; it took about a dozen phone calls and one missed appointment to get to this moment.

He hasn’t eaten in a restaurant in eight years. He doesn’t watch TV (“That shit’s a distraction”), and he listens only to instrumental music (“Lyrics are another part of conditioning”). He owns two different kinds of gas masks, a hand-crank flashlight, a generator. “I don’t rely solely on Con Edison for my electricity, the phone company for my communication, the television for my education, and definitely not the supermarket for my food,” he says. He has most of his food shipped to him, freeze-dried, and over the years he has found that there are certain bugs that you can eat.

He carries a white plastic shopping bag. Inside is his kit, containing a multi-tool, antibiotics, bandages, a long knife. Sometimes he spends weeks looking for just the right piece of gear. The gas masks? The artillery? They’re at home, in an outer borough, itself a feat of urban camouflage. “My home looks like no one lives there,” J. says. “That’s the best thing about it. You can walk right by it, just like someone could walk by me and not take me seriously. I like that.”

He does keep guns there – “weapons that I would consider legal” – but he doesn’t like to talk about them. And with an eye to the next attack, he’s selected a few neutral safe spots throughout the city where he can defend himself.

“A lot of people think survivalism is about being on a rooftop with a rifle, paranoid and afraid,” J. says, noticing a few more people taking seats on the lawn around him. “I mean, if it had to come to that, I definitely see myself doing the same thing.”

J. has crossed paths with at least 60 others like him in the city – nouveau survivalists who are equal parts urban and apocalyptic, methodically preparing for a future that was unthinkable to most of us before last September. “I’ve met them, all races, all sizes, even women,” J. says. “Some of them are very extreme. I feel like I’m in the middle. They’re fucking paranoid.”

With that, he stands up: “I’ve got to meet someone.” I shake his hand and start to walk away, but he calls me back.

“After today, if I see you on the street, I don’t know you, you don’t know me. And don’t call me anymore. It has to be that way.”

Aton Edwards has been referring to the World Trade Center as “ground zero” for six years. At lectures. In classes. On the radio. After last September, more people started listening.

Aton is a towering, muscle-bound man who roams the city wearing a black baseball cap with a fallout-shelter-like insignia of his own design. His ears point outward from the cap’s sides, lending him a certain impishness, but most of the time he’s all business. With the exception of his steel-toed boots, he wears denim and tightly woven cotton exclusively, for maximum fire resistance. He carries a jacket with him at all times, even in summer, to limit his skin exposure in the event of a biological attack or a dirty bomb. On his left wrist, he wears what he calls the Bandit – a six-inch-wide leather utility band he designed with compartments for a tiny notepad, a pen, and a waterproof diving watch. His fanny pack, which he is never without, weighs twelve pounds. He made it himself out of rubber, neoprene, and stainless-steel mesh. Inside are eighteen different tools, including a soldering iron, a pencil-size butane torch, and three kinds of lighters. “The tools make it so much easier in any emergency,” he says. “Pliers can make the difference between life and death if you have to turn off the gas.”

Aton is something of a central figure among the local survivalists. To some, like J., he is a tenuous lifeline to the mainstream world; to others, he is a friendly front man, the one who puts a less threatening face on their worldview. In 1989, he founded the Preparedness Network, a nonprofit group, to spread the word about smoke hoods and gas masks and what he calls “improvisational adaptation” to emergencies. He’s since renamed it the International Preparedness Network, and has given lectures sponsored by, among others, the Reverend Calvin Butts and Al Sharpton. He says he’s enlisted sixteen other “instructors” who are as committed to urban survivalism as he is, walking the streets in their own pairs of steel-toed boots. At weekly seminars, mostly on the Upper West Side and Harlem, Aton figures, he and his friends have taught survival techniques to more than 2,000 people, many of whom, he believes, still carry around small survival kits to help them in a pinch.

Before September 11, it was easy to dismiss a lot of what Aton said as doomsday static. (One chestnut from 1999: “You’ve got people like bin Laden, who has been rumored to have set up a biological-weapons facility somewhere in Afghanistan. It’s only a matter of time.“) For years, he’d play guest Cassandra on two public-affairs talk shows hosted by Bob Slade on 98.7 KISS-FM, and people would call to complain about him. But on September 11, he was their star, on the air four times, and he’s been back more regularly since. Enrollment at his seminars overflowed last fall, and he had to get larger venues before they became too much to handle and he shut them down in the spring.

Aton has thought about leaving town; for years, he’s been planning to build a dome-shaped home in North Carolina, and he’s bought the land. But he has bigger plans now. Aton is pitching himself and his fellow instructors as “an adjunct to FEMA” – a civilian-volunteer corps that, with government help, could help mitigate the panic a terror attack would create. And though he stresses that his “preparedness” is a slightly modulated survivalism – brightened a shade or two for non-misanthropes – he does still keep one hand in the dark side, swapping survival tips and gear with loners like J. “The hard-core survivalists need to maintain their privacy because of the things they do and the things that they own,” Aton says. He doesn’t mention weapons, but he doesn’t have to. “There’s a little violence in it. Maybe I’m soft-pedaling it. There’s lots of violence in it. It’s ‘You’re gonna come for us, we’re gonna take something from you.’ They’ve been around for years, but this 9/11 thing has submerged them even more.”

Last fall, Aton found himself swamped with calls from friends of friends – frightened, well-heeled people who wanted to be prepared and were willing to pay for the privilege. “Remember Panic Room?” he says. “Well, let’s just say there are more than a few people out there who are more than ready to spend liberally to protect their families.” He’s installed cameras and microphones on the stoops of brownstones. He’s come up with a home recipe for pepper spray that’s stronger, more painful. When one woman on the Upper West Side told Aton, “Tell me what to get, and I’ll get it,” he shrugged and shot the moon: He told her to get a Taser, solar-powered emergency lighting, a twenty-band radio scanner with a signal booster, a seismic detector for her front steps (her conventional motion sensors weren’t working terribly well), a hydroponic kit for growing vegetables, and a mill for grinding her own wheat. She got it all. “People feel a little better afterward,” he says.

Inside his apartment, a few steps from the front door, Aton keeps a 90-pound black nylon duffel. This is his “grab-and-run” bag, for when the big one hits – or at least hits far enough away that he isn’t incinerated. Inside is a backpack, a first-aid kit, a flashlight with batteries and an extra lamp, heat-resistant smoke hoods with charcoal-activated air filters, a fire extinguisher, emergency candles, a solar-powered AM/FM radio, a multi-tool, a knife, a pry bar, rain gear, a small tent, a whistle, a water filter, duct tape, work boots, gloves, enough freeze-dried food to last four people 72 hours, and kitty litter (for “emergency human-waste disposal”). “I’m not trying to protect from Armageddon,” he says. “When it’s time for the lights to go off, there’s nothing anybody can do about that. This is really about comfort. I don’t like to be in a situation where I feel like I’m helpless. So what I’ve done is I’ve tried to hedge the bets.”

He reaches into his backpack and pulls out a wallet-size wad of orange heat-resistant plastic. He unfolds it. It’s a smoke hood with a charcoal-activated filter: Slip it over your head, curl your lips over the plastic mouthpiece, and breathe. It retails for $79.

“This little thing right here – if more people at the World Trade Center had it, even if it saved one person … “

After September 11, he sold more than 400 of them.

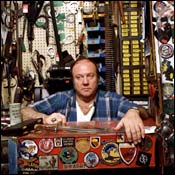

if you’ve ever had a passing interest in gas masks, chances are you’ve made your way to the Trader. The military-surplus store on Canal Street is the crossroads of New York’s survivalist world. It’s also where the movie people come for props and wardrobe, and where the tourists come, and the punks who are still into buying army gear. “Y2K – I couldn’t sell enough survival equipment,” says the Trader’s owner, Gary Hugo, a portly Romanian with a thick accent and a heavy sigh. “Masks, clothes, socks, pants, water purification. I couldn’t get enough, either. Just today, I sell a hand-crank generator.” Celebrities come, too – DMX, L.L. Cool J, Willem Dafoe, Johnny Cash. Grace Jones is a neighbor and loyal customer. “She’s very worried about survival,” Gary says. “I tell her, ‘Take a gas mask, the best one. The $300 one.’ “

A few things changed for Gary after September 11. He stopped renting out the front part of his store to some guys who were selling pirated videos; he says he just didn’t know them that well, but he also knew he was getting a little more scrutiny from the authorities. He moved the 81-mm. cannon and six-foot bomb casing inside, where they would raise fewer people’s blood pressure.

Lately, Gary’s been saying that he’s getting tired, and that the Trader could be gone by the end of the summer. He has six bids on the space. They all want to put in another Canal Street gift shop. Gary would rather sell to someone like Aton, who’d keep the Trader up and running, and Aton is tempted. They both feel the place has played a small but crucial role in world events. “Remember Chechnya, when they were fighting the Russians?” Gary says. “Some guy came here for uniforms for the Chechens. He only bought twelve at a time so they wouldn’t be noticed. Tall guy.”

A few weeks ago, some other guys walked into the Trader and asked for night-vision goggles and range finders. Gary, who believes he has a facility for placing accents, decided they were from Kuwait. He called the NYPD’s intelligence division, the number of which has been on a note pasted next to his register since last September. A car came immediately and some plainclothes cops ushered the guys out of the store – no longer Gary’s problem.

Gary notices survivalists all the time. One, named Clayton, has a garret in Pennsylvania that’s completely covered by earth. He maintains a five-year supply of firewood; the chimney and ventilation ports are protected so that when society collapses, no one can get to him. And yet, in a pitch-perfect illustration of urban cognitive dissonance, this same man pays for this lifestyle by working in New York City, commuting through barely protected bridges and tunnels twice a day.

Gary says he can tell at once the difference between army-surplus dilettantes and the hard-core survivalists: “The real guys, they ask for coveralls. Mosquito netting – the mesh that you attach fabric to so you seem invisible. The tree holders, the things where you sit in the tree. The handheld generators. Special kinds of warmers, fire starters. Foods like military foods, rations. Good machetes, not the regular cheap ones.”

A woman down the aisle overhears this and turns to her red-haired boy, who’s about 9 and wearing olive army fatigues: “That’s it. We’re done.”

When Aton was in the sixth grade, a teacher, Miss Hirsch, found him a copy of H. G. Wells’s The Shape of Things to Come. That was it for him. The premise of the novel is, like Aton, both resigned to doom and desperately hopeful: Warlords dominate a decimated, bombed-out planet … until a fringe movement of craftspeople and scientists forms a collective, creating a society free of war. “No bureaucracy either,” Aton says. In seventh grade, he read Buckminster Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth – in which humanity is imagined as journeying through the abyss, our fates inextricably linked – and he practically committed it to memory. “My copy’s torn apart, but I still have it,” he says. “He had the vision. Why aren’t we living it out?”

When he graduated from City College, Aton started to proselytize, first as a stand-up comic. “His famous bit was about how the people in the missile silos probably can’t even read,” remembers Kim Coles, a comic who met and married Aton in 1985 (and later went on to star in the sitcom Living Single). “His bit was, one kid says to the other, ‘I’m hungry,’ and the other kid says, ‘Press that button – it says LAUNCH.’ Some people laughed, and some people didn’t.”

Coles wasn’t always up for it, either. “It’s depressing to believe at any minute something major will go down and it’s all over. He told me he had a cave picked out for us. I can’t live like that.” They split up in 1991. “But thanks to Aton, I’m ready for it. I have a stash of water, I have several flashlights.”

On the morning of the 11th, Coles madly dialed and redialed Aton from California. She finally reached his cell as he was standing on the terrace of his Cobble Hill apartment, watching the Trade towers tumble. “I said, ‘You were right,’ ” Coles remembers. “And he said, ‘I told you, I told you.’ He wasn’t at all frantic. He was calm.”

After hanging up, Aton turned to Ginger Davis, the mother of his 3-year-old son and his partner in preparedness for more than ten years. There was no screaming, no crying.

“Well,” Ginger said, “I guess it’s time to go. Do we get on the BQE? Or do we go downstairs and get the raft?”

In his spare time, Aton is preparing a preparedness manifesto. The latest draft is 430 pages. There’s a chapter on building low-cost dome-shaped homes in hurricane country, and other chapters on fire, flood, nuclear meltdown, biological warfare. While FEMA manuals offer such useful tips as “Tune in to television and radio reports for official information,” Aton’s book envisions a world where humans rely on their wits to survive, employing a mishmash of disciplines from the martial arts to Taoism. Today’s society, he explains in Chapter 3, is slothful, sedentary, obese, and dependent on technology. He extols the survival skills of cavemen, who “make the modern city slicker seem feeble in comparison.”

It’s less a survival manual, really, than a guide on how to be Aton Edwards – a treatise on his “improvisational adaptation” plan. “Most emergencies, they happen unexpectedly,” he says. “It’s the old Murphy’s Law scenario: Whatever can go wrong will. And usually, you’re not gonna have what you need to deal with whatever particular crisis that you find yourself in. So you have to improvise and adapt – hence ‘improvisational adaptation.’ “

The book, Aton believes, could one day take the place of his survival classes, making his philosophy available to everyone, especially FEMA. “I know there are things we know that they don’t know,” he says. “The government wants to prepare the infrastructure, but they’re not preparing the population. And the thing is, it’s so much cheaper to just tell the American people ‘This is what you need to do,’ as opposed to just saying ‘Well, we’re gonna watch you, and we’re gonna take care of this.’ For them to take care of us just gives the terrorists more power. You know, people are adults. They’re not children. And they’ll accept responsibility for their own actions. You have a prepared population, they’re not powerless.”

For Aton, a large part of preparedness is having the right tools, so I ask him to show me what’s inside his stainless-steel-mesh fanny pack. It takes a half-hour for him to extract and explain absolutely everything, from the manual chain saw to the scissors that EMTs use to clamp blood vessels. “Now, my kit weighs twelve pounds,” he says. “Nobody’s gonna carry this around. But a regular person’s kit weighs about two pounds, and it’s something that can fit in anybody’s backpack, briefcase, bag.”

“So, what’s in that small kit?” I ask.

“A hand-pump flashlight,” he says, “one that doesn’t need batteries.” A good multi-tool with pliers – “not scissors, because a sharp knife is always better than scissors.” The multi-tool should also have a file or metal saw and a screwdriver – good for opening grates for air, or elevator panels, or to bend things back. Or you can use the whole multi-tool to pound like a hammer.

Bring some matches – for sterilizing. Alcohol swabs. Pain reliever with an anti-inflammatory, like Advil or Motrin – “good if something has dropped on you.”

Eye drops. A product called Dermabond can close cuts without stitches. Gauze. Band-Aids. (“Females can use Maxi pads – they absorb a lot of blood.”) And little vanity items, like a toothbrush, soap, a comb. “Because quite frankly, the philosophy is, every time you leave your home, you don’t know if you’re gonna be able to go back.”

What about money?

“Oh, yes. Emergency money. I do have money in my personal kit, but it’s buried so deep that I haven’t even seen it. It might be powder by the time I get to it.”

How about a passport?

Aton sneers. “If it gets to the point where you need to carry a passport all the time,” he says, “then we’re in deep doo-doo. If you have to cross borders, you’re pretty much dead.”

Then, just as quickly, Aton brightens.

“But I’m not saying it’s not practical,” he says. “Because I can tell you that my passport is in my 72-hour kit.”

PLUS:

The 72-Hour Kit

It can’t happen here … but if it does, you’ll want to be prepared. Below is a survivalist-certified checklist of everything a New Yorker might need to survive in the urban wilderness.

Questions of Survival

Everything you always wanted to know about being afraid of terror, asked.

The Luxe List

Want to rough it in style? Get out your credit card.