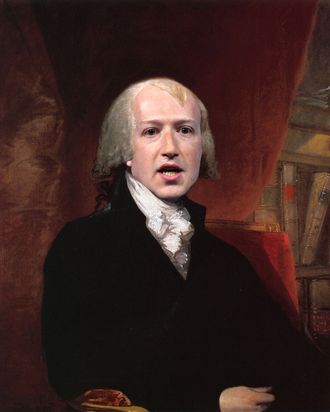

In a lengthy interview published today, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg attempted to explain to Recode’s Kara Swisher why his platform wouldn’t ban Holocaust deniers:

[A]t the end of the day, I don’t believe that our platform should take that down because I think there are things that different people get wrong. I don’t think that they’re intentionally getting it wrong, but I think —

Swisher: In the case of the Holocaust deniers, they might be, but go ahead.

It’s hard to impugn intent and to understand the intent. I just think, as abhorrent as some of those examples are, I think the reality is also that I get things wrong when I speak publicly. I’m sure you do. I’m sure a lot of leaders and public figures we respect do too, and I just don’t think that it is the right thing to say, “We’re going to take someone off the platform if they get things wrong, even multiple times.” What we will do is we’ll say, “Okay, you have your page, and if you’re not trying to organize harm against someone, or attacking someone, then you can put up that content on your page, even if people might disagree with it or find it offensive.”

I won’t impugn Zuckerberg’s intent here, even if I don’t quite understand it, but it’s worth noting that Swisher’s question was really just a more contentious version of the question posed last week by CNN’s Oliver Darcy, in an on-the-record meeting between the megaplatform social network and a group of media reporters: Given Facebook’s stated commitment to ending its misinformation problem, why hasn’t it banned the extremely popular official page of Alex Jones’s notorious conspiracy clearinghouse Infowars? As Facebook put it in a tweet a day after the meeting: “We believe banning [pages like Infowars] would be contrary to the basic principles of free speech.”

This answer (like Zuckerberg’s riff on Holocaust denial) wasn’t particularly satisfying to people. In a hearing on Tuesday, congressional Democrats posed more or less the same question: “How many strikes does a conspiracy theorist who attacks grieving parents and student survivors of mass shootings get?” Representative Ted Deutch asked.

It’s hard not to be sympathetic to Deutch here, and not just because his district includes Parkland, Florida. Infowars has, among other things, claimed that the Sandy Hook shootings were a staged “false flag” event, that Democrats were planning on launching a civil war on July 4, and that the government is putting chemicals in the water that are turning frogs gay. At the very least, setting “banning” aside, it seems less than ideal to allow a publication like that to represent itself on Facebook as a “News & Media Website.” Similarly, Holocaust deniers are engaged in a specific political project intended to diminish the impact of anti-Semitism and rehabilitate the Nazi state. It’s naïve, at best, to say you can’t “impugn” their intent.

But at the same time, you can understand the company’s anxiety. It’s not just that Facebook is wary of activating the grievance machinery of modern conservatism (though it very obviously is), it’s also that it has a philosophical, institutional allergy to making qualitative judgments about truth and falsehood. And, frankly, shouldn’t it? I’m pretty sure that I don’t want to live in a world where Mark Zuckerberg gets to determine what counts as true and what doesn’t, even if he and I agree about Infowars and the Holocaust. (Especially since he seems to be under the impression that there’s some large portion of Holocaust deniers who are merely misinformed, not actively mendacious.)

This is the impasse that we’ve been at for the last two years (at least): On the one hand, we’re uncomfortable with placing Zuckerberg & Co. in roles where they explicitly act as censors. (And have been extremely critical of Facebook when it has enacted that role.) On the other hand, well, you know, it’s Infowars, for Christ’s sake. It’s Holocaust deniers. Come on! (One common view among smart-tech critics is that we’ve reached this particular impasse because we took a very wrong turn somewhere, and in ceding much of the open internet to companies that sell attention to advertisers, have also ceded even the possibility of a healthy civil discourse. This view is almost certainly correct.)

What each side of this conversation has in common, whether they acknowledge it or not, is a fear of Facebook’s power: Its power to activate prejudice at scale, by giving Infowars a platform, or its power to cut off a key distribution channel for any given publication. Even Facebook itself seems afraid of that power: “I don’t think that we should be in the business of having people at Facebook who are deciding what is true and what isn’t,” Zuckerberg told Swisher. Facebook’s invocation of “free speech” and Zuckerberg’s insistence on discussing his business decisions in philosophical terms could easily be seen as cynical distractions. But they’re also tacit admissions that the company has attained a level of power over the digital public sphere where its moderation decisions need to be framed in the language of rights.

We have a name for that kind of power: sovereign power, as in supreme and unchallenged. It’s the kind of power that until recently we only associated with states, but that increasingly also lies in the hands of other, non-state institutions — suprastate entities like the E.U., but also the global megaplatforms that own the internet: Apple, Google, Amazon, and Facebook. Zuckerberg correctly insists that Facebook is a “company,” not a nation state, but it’s become something that resembles a state when you squint at it — it holds near-supreme power over media and civic attention. But rather than the liberal, rights-based sorta-state we all seem conditioned to expect — and that Facebook implicitly encourages, with its invocation of free speech and its reliance on legalish mechanisms like “community standards,” which can be “violated” — the platform is essentially a dictatorship, with none of the transparency, accountability, or checks on power we associate with liberal states. This is the tension on which the Infowars/Holocaust-denial problem turns — if Facebook is indeed a sovereign power, we don’t want it to be a dictatorship. But we also know it’s not a liberal democracy.

What, then, do we do? One solution would be to, well, turn it into a liberal democracy — or at least something near to that. In a recent essay, the lawyer (and recently named president of Demos, a liberal think tank) K. Sabeel Rahman suggests that we’re reaching a “quasi-constitutional moment” for Facebook and its fellow megaplatforms like Google and Amazon. For Rahman, the way to ward off the “arbitrary, dominating power” of “quasi-sovereigns” like Facebook is through constitutionalism — that is, the design of institutions to ensure accountability, transparency, and clear limits on power structures. In other words, Facebook needs a constitution. Maybe not a literal, actual constitution (or maybe so!) — but some kind of new power structure needs to be imposed for it and the states whose sovereignty it threatens to make peace.

If we believe that the problem with Facebook is that it has sovereign power without accountability, there are at least three paths to “constitutionalizing” it. The first, and the one currently attracting the most energy, is essentially to disempower Facebook, possibly to the point where you couldn’t describe its power as “sovereign” at all. Regulate it, break it up, enable new competitors: All of these solutions would have the effect of checking Facebook’s power such that it would no longer really represent a threat to sovereign state power. This set of solutions would “constitutionalize” Facebook obliquely, the way Brandeisian law and the New Deal “constitutionalized” the American industrial revolution and the sovereign powers it had enabled or created. A less powerful Facebook operating against a greater number of social networks might feel more competitive pressure to ban Infowars and Holocaust deniers — as well as more freedom to do so because the company wouldn’t be dominant over the public sphere in the same way.

The second path would be to formalize Facebook’s sovereign power under the aegis of the U.S. government’s. At the most extreme: Nationalize it. At the most realistic: Treat it as a public utility or a common carrier, subject to stringent rules of service and access. Solutions like this would “constitutionalize” Facebook by making it accountable to the U.S. government’s already-extant broad constitutional responsibilities. This could, in some circumstances, have the effect of opening Facebook up — making it transparent to records requests that demonstrate how its sorting algorithms work, and what effect they have on which publications, for example.

The third, and my personal favorite because of its weird, sci-fi implications, would be for Facebook to “constitutionalize” itself. That is, what if Mark Zuckerberg and his fellow executives-slash-founding-fathers drew up a compact with their “citizens”? One that outlined clear rights, enumerated powers, and established transparent mechanisms for the exercise thereof? This sounds like the least realistic option on the one hand — Facebook, a for-profit company built to sell ads, has no interest in turning itself into a much messier, much less efficient, and almost certainly less profitable platform — but it’s also the direction Facebook itself has been moving toward, as it emphasizes its community standards and moderation processes, elevating them to something like a legal code and judicial process.

But (as the Infowars controversy reveals) mere gestures toward a liberal system on its platform are inadequate, and no substitute for the real thing. Facebook’s invocation of “free speech” is as much a “legal talisman” intended to ward off criticism without accepting responsibility — and any real constitutional change will require it to accept that responsibility. The E.U., in passing and prosecuting a body of law that sharply limits Facebook’s powers and protects its users, is demonstrating, at least in part, how to apply the right kind of pressure. Facebook now has a choice: It can fight to retain its unchecked power and dominion, or it can actualize some of its gestures toward transparency and accountability, becoming the great liberal-democratic platform it pretends to be.

Would a Facebook constitution “solve” the Infowars problem? A good one that balanced the competing needs of the public sphere, individual freedom, and civic health, and that gave people a voice in and an understanding of the decisions being made by the platform, might at least get us as close as it’s possible to come. The point, as with liberalism generally, wouldn’t be to reach unanimous agreement, or to come down hard on one side or another, but to create a system in which power is distributed among many, and in which grievances are heard, treated with respect, and resolved fairly. If nothing else, Zuckerberg would have to undergo fewer uncomfortable interviews.