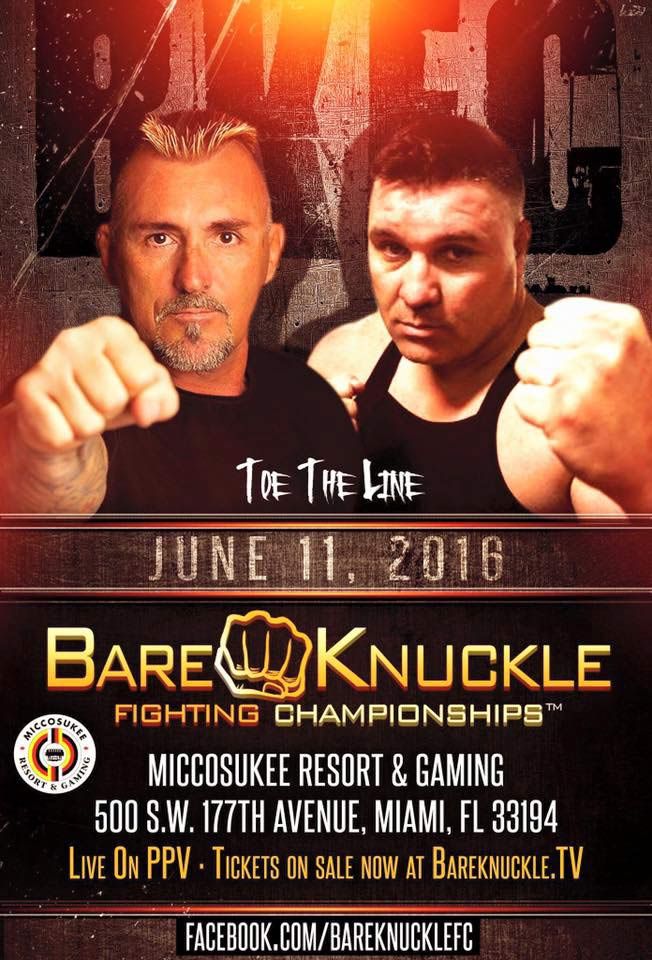

Bare-knuckle boxing in the United States was expected to “[come] out of hiding” on Saturday, June 11, as Rolling Stone reported breathlessly back in April. But the planned match between Bobby Gunn and Shannon Ritch — billed as the first sanctioned bare-knuckle-boxing event in the country in five years, and only the second since 1889 — was canceled at the last minute, a decision attributed to the twin passings of Muhammad Ali and Kimbo Slice, which means that America will have to wait a little longer for its bare-knuckle awakening.

Rumors abound in the boxing and MMA worlds that the deaths are simply being used as a convenient excuse for the fight’s promoters to cancel the event because of lagging ticket or pay-per-view sales. And the press release announcing the postponement indicates as much, noting that “Our PPV Broadcast Partners have expressed the need for a more comprehensive Global Advertising and Marketing Campaign that is imperative to the ultimate success for an event of this Historical significance and importance.”

As of press time, the organization’s website carries no announcement of the event’s postponement, leaving ticket-holders to request refunds via Facebook message. But there are indications that the fight may never have been scheduled to begin with. Contacted by New York, the events manager of Miccosukee Resort and Gaming, which has been advertised as the location of the would-be bouts since April, said she didn’t know anything about a bare-knuckle event planned at their resort. She added that the resort had no bookings of any kind penciled in for the day, and that she had told “a couple” of ticket-holders seeking refunds the venue had no knowledge of the event. Dave Feldman, one of the fight’s promoters, insisted that organizers did in fact have an agreement with Miccosukee, adding, “We would not promote a fight where we didn’t have a contract.” When asked to provide a copy of the contract or correspondence with the venue, however, Feldman first replied that he would “look into whether or not it makes sense to turn over [that] info to you,” then said he would do so on Monday. (We will update the post when and if he does.) He promised that tickets for the canceled match would be refunded.

Whether a bare-knuckle boxing match can be legally held, even on a reservation, remains an open question. As lawyer and blogger Erik Magraken points out, Federal law requires that boxing events on Indian land must have safety requirements “at least as restrictive” as those in the applicable state. And Florida requires boxing gloves. The Florida Boxing Commission therefore declined to sanction the event, and indicated that “Anyone who participates in or organizes such an event is subject to administrative and criminal penalties.”

Meanwhile, bare-knuckle boxing is faring somewhat better across the Atlantic, where it has always been legal, steadily building a fanbase and gaining legitimacy in recent years. Michael Ferry, a 25-year-old father of two from Wallsend, England, is reigning heavyweight champion of the World Bare Knuckle Boxing Council, a sanctioning body with more than 300 fighters. Having switched over from regular boxing three years ago, Ferry, who also holds the British and Transatlantic titles as awarded by the UBBAD, admits he had some trepidations about taking the gloves off at first. His wife still does. “She stays away from the fights,” Ferry explains. She did attend a few bouts at first, but found it too stressful to watch. She now keeps her distance. “I ring her after the fight and tell her how I get on,” he jokes.

Counterintuitively, there is a growing body of evidence indicating that bare-knuckle boxing may actually be safer than the gloved variety. Whereas regular boxers can trade massive blows by the round, bare-knuckle boxing tends to favor a cerebral approach. Opponents are more careful to avoid blows to the head, where, as you might guess, getting hit really hurts. “Your face is getting split, and you feel the punches more without the gloves,” Ferry says.

Defensive tactics, which have always been essential to what A.J. Liebling called “the sweet science,” become far more so when the gloves come off. “With a bare hand it’s totally different to gloved boxing,” Ferry says. “When you connect with no glove on — especially if you’re a heavyweight — you either knock them out or you stop them. You have to pick your shots and be wise enough when you’re throwing your punches to not get caught by your opponent.”

In the last three years, Ferry has dominated the sport, winning all but one of his fights in the first round. “He really makes his punches count,” says Stu Armstrong, part of the World Bare Knuckle Boxing Council (WBKBC). “He doesn’t throw a lot.”

As for the widespread perception that boxing gloves make the sport safer, a landmark 1993 report by the British Medical Association (BMA) concluded that “gloves are designed to protect the fists of the wearer and do nothing to prevent brain injury unless they are so large as to be unwieldy.” The argument is that ungloved boxers simply cannot punch as hard or as often as those wearing gloves, due to the risk of seriously injuring their hands. As a result, the risk of doing serious harm to their opponent is greatly reduced. Which means that decades of supposed medical advancement in boxing safety may have actually made the sport more dangerous.

“It’s true that boxing with gloves gives you greater force,” says professor John Hardy of the department of molecular neuroscience at University College London, who isn’t a fan of any type of boxing. That force means there’s a greater rotational effect on the brain, resulting in chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE — the condition once known as “punch drunkenness.”

To be clear, no scientific research published anywhere shows that willingly submitting to getting smacked around the head for 12 rounds of three minutes’ duration, gloves or no gloves, is a good thing. “Presumably the intention is just as in normal boxing,” Hardy says, “to knock the opponent out. If that is the intention, it is to cause brain injury, because that’s what a knockout is.”

As for the relative differences between the two forms of the sport, Professor Hardy affirms that “there’s a degree of truth in what has been said about bare knuckle boxing,” but he adds, “the intention is still to cause head injuries. A head blow is a head blow, regardless of the force.”

There’s also the health of the person who’s throwing the punches to think about. Without ten ounces of padding on your fists, connecting with someone else’s skull can do serious damage to one’s knuckles. “A fighter can very easily break their hands,” says Armstrong. “Short-term damage is more likely in bare-knuckle boxing — things like a broken nose or broken hand.” Nonetheless, he argues that long-term it’s “massively” safer than gloved boxing.

Dr. Alan J Ryan, a pro-bare-knuckle campaigner who died in 2005, pointed out in 1998 that “in 100 years of bare-knuckle fighting in the United States … there wasn’t a single ring fatality.” In today’s gloved sport, deaths happen more frequently.

Despite the science — and perhaps because we’ve become accustomed to prize fighters wearing bright-red gloves in glitzy contests that give off the veneer of a professional, regulated, TV-friendly sport — a bare-knuckle match still seems sketchy, conjuring images of bloody brawls in backyards rather than sell-out crowds at the MGM Grand.

“There’s still a stigma,” Armstrong admits, going to some lengths to detail the rigorous drug testing and medical screening fighters must submit to. “That’s the biggest battle we’re facing, but in the past couple of years we’ve managed to show people it’s not in hay bales or back lanes; that it’s a professional sport.”

And the potential prize is huge, Armstrong believes. “Three years ago, you had maybe 30 people watching in a barn somewhere.” This year bare-knuckle boxers sold out two 1,500-seat venues in the U.K. That’s still fairly modest, but promoters see parallels with mixed martial arts (MMA), and particularly UFC. “Where we are now is just at the point where the UFC exploded,” Armstrong says.

Back in the 1990s, UFC was seen as little more than human cockfighting, held in gritty blood-spattered cages with minimal safety considerations. In 2016, it’s a legit megasport, firmly implanted in the mainstream, an acceptably adult WWE with all the kudos and merchandising opportunities that entails. Bare-knuckle boxing is still a long way from that kind of acceptance — especially in the U.S., where Saturday’s canceled fight is not likely to help matters much — but proponents have only just begun to fight.