Shortly after I turned 21, I began seeing someone twice my age and soon fell victim to that exhausting, obsessive sort of desire that had the object of my ardor infiltrating all my thoughts all the time. I felt utterly helpless, except when we were actually hooking up. His ironically boyish excitement — a 21-year-old! with 21-year-old breasts! — filled me with bliss.

I never called him “daddy,” but, oh boy, was he daddy. My therapist once pointed out the parallels between my relationship with him and my relationship with my father. It made me feel yucky, viscerally nauseated. I’m making peace with it, though, because you can’t escape your circumstance, your patterns, your daddy, other daddies, the daddy.

I’m not into dads, per se, but I can sure as hell fuck with a daddy. A daddy is an imperfect combination of authority and appreciation; a man my age (early 20s) is none of those things. A daddy is older and probably acts like he knows better than you; you’re okay with that. The ecstasy of a daddy is that he doesn’t just treat you like a hot girl; he treats you like a holy temptress. The gratefulness of the daddy — his visceral, physical urge for your young-ass body — complicates the power dynamic created by your vast age difference.

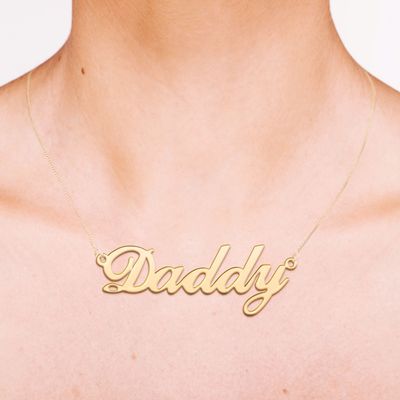

I am not alone when it comes to my love of daddy. It’s trendy for millennial women to proudly declare their daddy desires. (Thanks, Obama.) Moreover, daddy extends far beyond fatherhood and sexual fetishism these days — whether it be teens replying to celebrity tweets, the freakishly popular Daddy Issues Instagram account, Beyoncé’s “Daddy Lessons,” a Broadly article about why women like to call men daddy during sex, or a BuzzFeed quiz that allows you to determine what percent daddy you are. “Daddy” is a meme, and it’s fire as fuck.

What “daddy” signifies in the 2010s is forever morphing and expanding, from parenthood to a way to express sexual deviance to sex work to gay slang to meme. At this point, it’s ineffable: A daddy both is and is not a real live person because a daddy is an adjective, noun, and rubric of measurement. You might moan “yes, daddy” in bed out of pleasure, as a coy neg, or a little bit of both.

Our current conception of “daddy” is, in part, derived from “daddy issues,” a pejorative way to categorize a certain type of unmanageable woman, as in, “She’s a crazy slut because she has daddy issues.” The concept of “daddy issues” stems from from Jung’s Electra complex, a feminized Oedipus complex. The trope appears again and again in pop culture, used to identify the root of psycho-bitch promiscuity. By the mid-aughts, it became ubiquitous, frequently referenced on the bro-beloved sitcom How I Met Your Mother by its most misogynist character, pickup artist Barney Stinson.

If you grew up with an absent father like I did, hearing boys and bros describe daddy issues as the cause of any bad girl’s slutty or unhinged behavior — and malign her for said issues — always stung deep. I don’t remember when I first learned the meaning of the phrase, but from a young age “daddy issues” always felt like a prophecy for me, a distinctly unempathetic way of interpreting how damaged and difficult I was.

Sylvia Plath shaped the way millennial women think about dads, daddies, and daddy issues. In her mercurial and possibly autobiographical 1962 poem “Daddy,” she frames the narrator as potentially part Jewish and the daddy as a Nazi sympathizer. Throughout the poem, the narrator retraces her abject relationship with her dead father — whom she only refers to as daddy, not dad, not father — talking herself out of loving him. She writes:

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

Although the poem ends on “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through,” any girl with daddy issues knows trying to rid yourself of your infatuation with daddies is a Sisyphean task: We’re both obsessed with and haunted by daddies, both literally and conceptually. We’re seldom “through,” and when we are, we’re sure as fuck not writing poems about it. Your relationship with your dad might be temporary, but your relationship with “daddy” is forever.

What differentiates today’s iteration of daddy from past conceptions is we’re having way more fun with it. In contrast to Plath’s depressing, deep-ass daddy poem, our “daddy issues” manifest differently. We seek men who embody the most erotic elements of the daddy, and we have fun doing so. Anna*, a millennial woman who mostly dates daddies, tells me, “The most important thing about being a daddy is that a man has a sort of nonchalant confidence in his own masculinity and place in the world.”

We’re not into daddies because we want to be babied or provided for, though a daddy is far more likely to cover your Uber home at the end of the night than his millennial counterpart. Every woman I interviewed about their daddy desire told me that the appeal of the daddy stems partly from the fact that these men have their shit together. The infinite studies and think pieces about the horrors of noncommittal millennial hookup culture aren’t always accurate, but they’re not wrong. “Daddies are great because they’ve mostly worked through their youthful neuroses and become more reasonable human beings,” Anna explains.

The non-daddy, on the other hand, can suck the emotional energy right out of you. The millennial man might not respond to your text because he has “a lot of shit going on,” but the daddy always responds. He might take longer than expected, but when he tells you he wasn’t with his phone or was busy with work, you believe him. Because the daddy has a decent job, and the daddy didn’t start texting until he was a literal adult.

Jessica*, a millennial woman who dates daddies and non-daddies, explains why she prefers the former: “The 20-something men I’ve dated do not value my presence in their lives like older men do.”

Jessica and Anna are both open online about their affection for daddies. Anna explains, “Men have been specific and insistent about their ‘types’ forever, and it feels a little subversive to be so frank and crass in public about the men I’d like to fuck.”

Sarah*, another daddy-loving millennial woman, has a more straightforward reason she likes to call men daddy during sex: “I feel like if I stroke a man’s ego like that he might fuck me better.”

Our recent reclamation of the daddy is not only a big “fuck you” to anyone who’s ever maligned us by saying we have “daddy issues”; it’s also a fun way to flip the script, especially on the internet where women are subject to a deluge of misogynistic harassment.

Our tweets about daddies are jokes, and at this point they’ve surpassed our sexual desire for daddies. “Daddy” is a nebulous concept. Writer and comedian Fran Hoepfner, a master of daddy jokes, explains, “Daddy jokes came after the popularity of ‘my son/my wife’ jokes, and if ‘my son/my wife’ jokes are about men finding it funny to take responsibility for another human, ‘daddy’ jokes are about finding it funny to defer to a [heterosexual cisgender man] in an authoritative way (be it sexual or not).”

We like to make jokes about daddies because there’s something inherently uncomfortable in the term. Calling the men you like or want to fuck a pet name for father makes people squirm because it allows you to openly play out your parental desires in a sexual and vulgar way. The daddy joke allows the teller to become daddy themselves.

Comedian Blythe Roberson’s daddy jokes often involve her embodying the dad. “I do sometimes feel weird about calling myself daddy, like it will reveal to me my internalized misogyny,” she explains in an email. “I was hanging with a dude recently, and ‘as a flirt’ I was trying to get him to call me daddy. When he asked me why I am daddy, I said: Because I am in charge!”

What’s so funny about the daddy joke? The daddy joke is that it’s a joke that your father would take good care of you. The daddy joke is that now you want to fuck men who resemble your father in some way because of that care. The daddy joke is that you’re ostracized for playing into this and admitting it, and the daddy joke is that your father isn’t.

“Daddy” implies authority, and the daddy joke is, Fuck you, daddy, that doesn’t mean shit to me.

The mad beauty of our love of daddies is that the women who now blithely spit the word in any context own daddy. No matter how softly we say the word, it comes across as sharp, brutal. Saying “daddy, please” in a sext or in real life isn’t necessarily an act of submission; it’s a proclamation of our desire for them, of our awareness of their desire for us. A grown woman says daddy with intention, self-assurance, and lots of cynicism. We claimed “daddy” as our own, which allows us to gently mock the patriarchal structures we’re playing into. The daddy joke is that we have control over the way we manifest “daddy”; that we could, one day, even become our own daddy. (The daddy joke is we know we can’t.) And sometimes the daddy joke isn’t a joke at all. Sometimes we just want to fuck a daddy, and what could be funnier than that!

*Some names have been changed.