In early November of 2014, my father was riding a four-wheeler across an open field with a group of friends when he hydroplaned, losing control and flipping several times. His brain was injured in the crash and he died a few days later.

I lived in California at the time and he was in Kentucky. I got the news about his worsening condition and ultimately, his death, from my older sister who was by his side in his final days. She wasn’t alone though. Along with a couple of our father’s siblings, truckloads of his friends stubbed out their cigarettes and piled into his ICU room to pay their respects to the man affectionately known as “Big Bruce.”

Like me, Chanell Wilson heard of his passing from across the country. The 20-year-old, who now lives in Arizona, was one of the many people who my father touched with his buoyant, childlike personality. As she recently told me, despite being a few decades her senior, he was her best friend. Still is, she says. When he died, Chanell was heartbroken. Unable to attend his memorial service in a gravel lot at a local gun range, she honored him in a much more permanent way.

“I got my tattoo because he’s close to my heart,” she told me, referring to the black and red piece stretching across the left side of her back. “Bruce Raymond,” it says, the second half of his last name curling downward. Under his name there’s a heart with EKG lines coming out of it, a popular conceit for tattoos commemorating the dead, and then this text, written in an unsteady cursive: “Forever in my heart. Always on my mind.”

Bruce, as I called my father even though he once chewed me out for it, came into Chanell’s life when her own father walked out out on her family. “He really really helped get me on the right track. If he wasn’t there, I don’t know where I’d be, or what I’d be doing,” she told me.

Funny, because I know where I’d be if Bruce wasn’t there for me—exactly where I am.

When my sister called me to say Bruce wasn’t going to make it, the first thing I thought of was the price of plane tickets from Oakland to Louisville. At least $800 for me and my wife. Add in the attendant costs of travelling and I was looking at spending $1,000 to pay my respects to a man who hadn’t spent $10 on me in over a decade.

I considered staying home, saving my money, letting everyone else sort through the old engine parts and piles of mugshot newspapers in his garage. But then I thought of my sister and our younger brother. I’d spent the previous decade away at college and after graduation, just away. My sister stuck around and our half-brother, only 13 at the time of Bruce’s death, lived with him. I resented our father for never making an effort to talk to me, but I had it better than they did. My sister talked to my father on occasion — any time he needed something from her—and my brother, who lost his mother in childhood, had just lost his father, who hadn’t yet had the opportunity to disappoint him.

So my wife, my one-year-old and I flew to Kentucky to go through the motions of mourning Bruce, who may not have even known that his granddaughter existed. I certainly didn’t tell him. We hadn’t spoken for six or so years by the time he died. I used to call him, but the conversations were superficial and pointless. So I called less frequently until I stopped calling altogether. Then, on principle, I decided to never call again. At least until he called me first.

He never did and that complete lack of interest in my life ate at me in the days after his death, especially when I saw how beloved he was in his neighborhood. He had the time to maintain dozens or friendships but couldn’t call his kid. I could have ended the unofficial silence at any time, but I’d come up with a reason not to. I was taking a stand against his negligence by neglecting him. Hypocritical perhaps, but I needed him to make an effort. When my daughter was born I only dug in deeper. Her birth gave me a new perspective on his willful disappearance from my life. How could the man who helped create me, want nothing to do with me?

He would have called me a pussy if he ever heard me say that. He would brushed off our silence and made excuses for it. We were both busy. I lived far away. He didn’t like talking on the phone. And anyway, I could have called him. I asked Chanell if he ever talked about me in the time they spent together, if this girl who my father cared for more than he cared for me even knew I existed. “Yes, he did love you and talk about you,” she said, “but things happen. Life happens.” Sounds like what he would have said.

Bruce and my mom divorced when I was three. Within a year, my mom had started dating a guy who, for nearly 30 years, has been my “dad.” He was there every day when I was growing up, supporting our family financially and doing the work required to help raise me. For that, I called him “dad,” while Bruce’s biological connection left him with the more clinical “father.” Once, without thinking, I referred to my dad as “my dad” while talking to Bruce. He corrected my error.

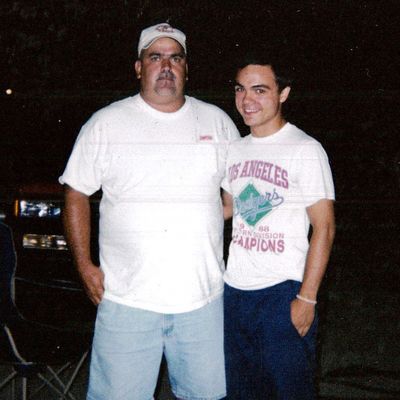

When I was about eight, after bouncing from California, to Georgia to central Kentucky, my family ended up in Louisville, about 30 minutes from Bruce’s house. Every other weekend, he scooped up me and my sister and brought us back to his house for 48 hours of fun under the big tent of his personal three-ring circus.

Bruce was always kind of a big kid, the personality for a dad when you too are a kid. When I was younger that meant dish soap slip ‘n’ slides on industrial sheets of plastic and road trips to Florida in the carpet-lined bed of a pickup truck. It had a topper on it, but still. As I reached adolescence, my dad’s laissez-faire parenting style made it easy to stay up all night playing video games and experiment with a pinch of Red Man chewing tobacco. He continued introducing me to the things he valued too, like Cinemax after dark and malt liquor.

Throughout my childhood, he instilled in me the value of an oft-repeated bad joke that, if told enough times, seemed funny again. Every birthday and Christmas he’d say he got me “a new butt, because yours is cracked.” As I got older, the jokes got bluer, like the limerick he introduced me that I still remember to this day: “There once was a man from Nantucket, who had a dick so long he could suck it. He said with a grin while wiping his chin, if my ear were a pussy I’d fuck it.”

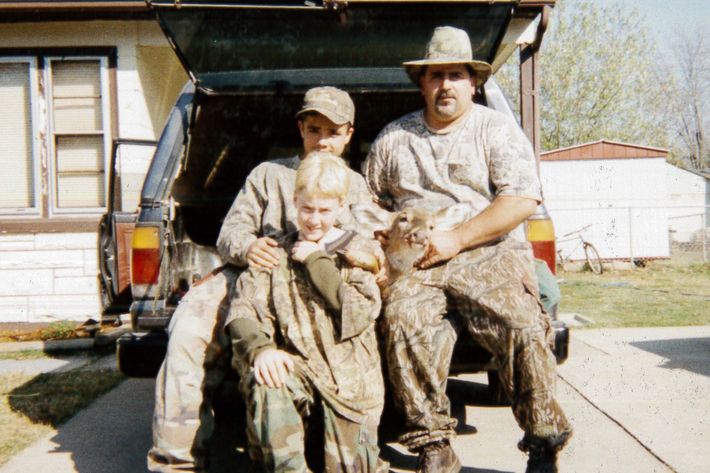

But the most important thing, from his perspective, that Bruce ever taught me was how to hunt. The man loved the woods and wore camo nearly everywhere he went. For years, he dragged me out of bed in the pre-dawn hours to eat gas station donuts in the chilly wilderness and listen for deer. One of my clearest memories of hunting is staring at a mass of trees and leaves for so long that I started to hallucinate. I swear I saw a vampire in those sticks.

I also remember the time Bruce shot a deer while I was standing next to him. My heart pounded under the extra-large Cabela’s shirt he lent me. I was typically bored senseless by hunting, but too meek to ever protest. In this moment though, I caught a brief glimpse of why he loved this sport. The silence of the hunt, followed by the pop of his rifle and the ensuing search for the body, was exhilarating. In the battle of man versus beast, we had won. For a guy with a learning disability, three failed marriages and emerging health problems, hunting provided a rare chance at a victory lap.

But hunting wasn’t for me and when I was about 14 I got the courage to tell him that. I’d stopped eating meat after reading a few factory farming brochures and embracing something of a revolutionary streak. I even took down a Korn poster hanging above my bed and spray painted an anarchist “A” on the back of it. Then I hung it back up with Jonathan Davis and company facing the wall. Right around that time, I first heard Crass.

Bruce didn’t quibble too much with my vegetarianism, which might sound odd for an avid hunter, but it was right in line with his, “Ehh, whatever,” approach to parenting. I don’t think it had anything to do with the fracture in our relationship either, but it was a sign that change was coming. I was beginning to make decisions about my life and, importantly, my time. I wasn’t available every other weekend to take scrap copper to the recycling plant or shoot milk jugs down by the Ohio River. Twice a month became once a month then once every few months. By the time I was going off to college, we were only seeing each other on holidays.

In the weeks after Bruce’s death, as I wrestled with why he let go of me, I decided that it was inevitable. When I grew up, he gave up, because suddenly, having a relationship with me required more of him. It was easy for Bruce to play fun-time party dad four days a month when his kids were always available and easily impressed. But when being in my life required extra effort, it was no longer worth it. Every parent must one day deal with a distant teenager, but mine couldn’t. So he didn’t.

In some ways, I was lucky. Millions of people have absent fathers who never saw their kids as much as mine saw me. But the strength of the bond we once shared is what made its disappearance so upsetting as I became an adult.

When Bruce died and I found out how beloved he was for serving as a father figure to people who weren’t his children, those feelings came rushing back. It felt like a callous betrayal. But the more I thought about it though, the more it made sense. When Chanell, the stranger with my father’s name tattooed on her back, was angry, vulnerable and young, Bruce was there for her. She lived nearby. For a time, he dated her mom. It didn’t take much effort.

In the end though, Chanell and I aren’t that different. When I was young, I had a tight bond with Bruce. It faded when he stopped trying. As I began resenting him for not caring about me, he started caring for her. But it didn’t last forever. She moved away from his neighborhood when she was 16 and he disappeared. “I hadn’t seen or talked to him for two years before he passed,” she told me. No doubt that two would have dragged on to three, and eventually 10.

Still, I suspect she would have continued loving him. To Chanell, Bruce was a caring man who stepped in when her own father walked away. She asked nothing of him and he exceeded her expectations. For that, he earned a permanent place in her heart and on her skin. But when he was called upon to be there for his own child, a significantly more difficult job, he didn’t even try. Ironic, considering I was the one whose name was tattooed on him.