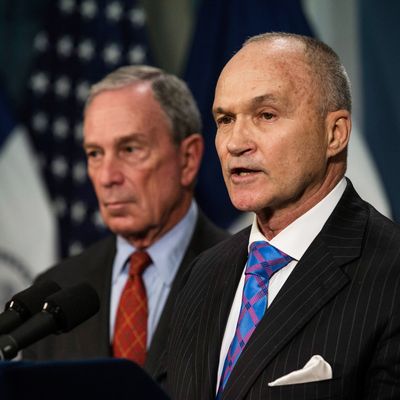

During the past two weeks, as it has become obvious that the argument over stop-and-frisk will be the last major political act of his administration, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and his police commissioner, Ray Kelly, have been conducting a media tour to defend the policy. Their argument has been that it has been effective in reducing crime, and that the NYPD’s liberal critics and Judge Shira Sheindlin, who recently ruled stop-and-frisk unconstitutional, have ignored the crucial arguments on behalf of the policy — namely, its effectiveness. “Throughout the trial that just concluded, the judge made it clear she was not at all interested in the crime reductions here or how we achieved them,” Bloomberg said at a press conference last week.

And yet the evidence that Bloomberg and Kelly have presented has proved only the overall effectiveness of the NYPD at reducing crime, not the specific effectiveness of stop-and-frisk. “NYPD: Guilty of Saving 7,383 Lives,” ran the headline on Kelly’s Wall Street Journal op-ed, but those 7,383 lives were merely the difference between the total number of murders during Bloomberg’s eleven-year mayoralty and the number during the eleven previous years. Kelly made no effort to link the reductions in murders to stop-and-frisk. During an appearance on Morning Joe, Kelly was asked point-blank whether stop-and-frisk specifically had reduced crime. “It is a component,” Kelly said, and then moved on. Which has left unanswered the most basic question about the policy: Does it reduce crime? So far this debate has been at a standstill. But scholars are getting more precise in their methods and analysis. And in the latest research — much of it still unpublished — it is getting harder to detect any effect from stop-and-frisk at all.

One way to examine whether the policy works — the way that some scholars have tried so far, and more are trying now — is to look at those geographic areas where stops escalated, and to try to see whether rates of crime declined afterwards. This is a very complicated statistical undertaking, though. First you have to control for all the variables that have nothing to do with policing that might account for some of that change in crime (changes in the socioeconomic status of a neighborhood, its levels of unemployment and home ownership, changes in its demographic makeup). Then, because escalation in stops in a particular neighborhood often takes place together with other policing efforts (more cops on the streets, more arrests and summonses generally), you have to disaggregate the effects of each of those efforts from the specific impact of each additional stop. (So in order to know what effect each additional stop has, you have to control for the simple effect of having more police in the neighborhood, and the effect of arresting more people, and the effect of issuing more summonses.) Then — without having access to the NYPD’s own strategies, which means without knowing exactly where they were targeting — you have to make sure that you are looking at the right geographic area and time sequence, to make sure that you aren’t missing some suppressive effect on crime that has occurred elsewhere, or at a different time.

These studies started out very crudely and have slowly been getting more precise. An unpublished — and therefor not peer reviewed — analysis by Dennis Smith of NYU and Robert Purtell of SUNY-Albany in 2008 looked at the effects of escalating stops in a particular precinct on crime rates in that precinct in the months that followed. Their results were mixed: They found that additional stops had an effect on some crimes (largest on burglaries and robberies, but also measurable on murders), though not on others (rape, assault). But there were many methodological problems with this study: It did not control for even the most basic complicating factors, such as the socioeconomic status of the residents. When Richard Rosenfeld of the University of Missouri-Saint Louis and his graduate student Robert Fornango (now of Arizona State) controlled for those socioeconomic and demographic factors and applied a more sophisticated way of looking at the time sequence, they found that Smith and Purtell’s effect disappeared, and they could not find any evidence that additional stops reduced burglaries or robberies at all. Rosenfeld and Fornango’s is the only peer-reviewed paper that directly deals with stop-and-frisk’s effectiveness. But it is itself so inconclusive that it has left the political debate wide open, with Mayor Bloomberg warning that the public safety gains of the last two decades may be squandered if the policy is abandoned, and Bill de Blasio arguing that it makes no difference at all.

But that is not the end of the story. As the rhetoric around stop-and-frisk has intensified, so have the efforts of researchers to estimate the effects of the policy more precisely. Rosenfeld is now working on a project to see what happened within much smaller geographic ranges — 5,000-person census tracts, rather than 100,000-person precincts — where the effects of a targeted policy might be easier to find and measure. He recently shared with me some of his preliminary findings. If you look at what happens to crime in a particular census tract after stops escalate, there is an effect — crime rates do get lower. But the scale of the effect, Rosenfeld says, so far looks tiny to him. “Thousands of stops are required to achieve even small crime reductions, say, a dozen or so [crimes] citywide,” Rosenfeld told me.

To be more confident in these findings, though, you would like to be able to control not merely for the demographic conditions of a neighborhood, but for the other policing interventions that tend to go along with the stops — for arrests, for summonses, and for the mere presence of cops on the street. (Each of these interventions likely has some effect on crime on its own, independent of stops and frisks.) Jeffrey Fagan, of Columbia Law School, is trying to do this. His study is not yet final, but so far, he said, it seems that stop-and-frisk, if properly isolated from the other components of policing, may actually increase crime rather than decrease it. If these findings hold, they might seem slightly paradoxical: It would mean that sending cops to a high-crime area reduces crime but actually having them stop people there does not. Many studies have found that the threat of arrest has a chilling effect on crime, but we don’t understand very well what it is that establishes the threat of arrest in the mind of a would-be criminal: The mere visibility of cops on the street, or their specific actions. If Fagan is right, then it may soon be possible to separate these questions statistically. “It is one thing to talk about where you send police and even how many you send,” Fagan told me, “it is quite another to ask what they should do when they get there.”

None of these projects are final, and many caveats apply. Both Fagan and Rosenfeld make their politics plain: Fagan consulted for the plaintiffs on the stop-and-frisk lawsuit, and Rosenfeld is working under a grant from George Soros’s Open Society Institute. Both of these projects (and there are others — David Weisburd of George Mason is also studying this data, and others likely are as well) may be canvassing too broad or too narrow a geographic area, or they may be controlling incorrectly for complicating factors. It may be, too, that the overall effects of the policy (in so far as it makes it less likely that people will carry guns in public) will have a chilling effect on violence beyond the narrow boundaries of a particular neighborhood. But still it seems fair to say this: Neither the Bloomberg administration nor the NYPD have yet shown that stop-and-frisk is an effective policy. Scholars are looking, with increasing sophistication, in the places where you might expect a crime-reducing effect from stop-and-frisk to show up, if one existed. So far, they haven’t found anything.

If you ask the Mayor’s office, this form of analysis is so targeted that it not only misses the potential effects of stop-and-frisk but misunderstands the whole point of the policy. “That sort of micro-analysis of large-scale trends is wildly flawed,” Marc LaVorgna, a spokesman for Mayor Bloomberg, told me. “Criminals don’t know how many stops are conducted on one block versus the next, or based on where lines are arbitrarily drawn on a researcher’s map. They know the police conduct stops in the areas where they operate. We have the lowest rate of teens carrying guns of any major city in the country — there is a reason for that.”

Part of the logic of stop-and-frisk has always been that it might work as a crime deterrent — that people who might otherwise carry guns would leave them home, worried about the consequences if they might be stopped. (Last week, a large federal sting operation aimed at gun traffickers captured one saying that he didn’t want to bring guns into central Brooklyn because of stop-and-frisk operations there.) There is some (circumstantial, but powerful) evidence that policing in New York is in fact deterring crime: Though most places in the U.S. have seen incarceration rates go up as crime has declined, the incarceration rate here has gone down, along with crime. But that leaves unresolved the matter of what it is about policing in New York that has had that effect.

Which raises the question of why Mayor Bloomberg and the NYPD have been so adamant about defending this policy, at some real risk to their own legacies and political futures. One possibility is that they have their own statistical analyses that show the policy is effective, though if that were the case, then hopefully they will make those studies public. More likely, though, the explanation is cultural. There is a particular report that beat cops must fill out each time they stop someone on the street, and the number of those reports increased 600 percent from the start of the Bloomberg administration to the present. (This is the source of many years of media reports saying that stop-and-frisk is dramatically on the rise.) But the great historian of the modern NYPD, Franklin Zimring of UC-Berkeley, told me that he didn’t trust those numbers — he thought it very likely that cops had simply not reported their stops at first, and that it took a while for the centrality of the issue and administrative pressure to seep through the NYPD’s bureaucracy. It is more likely, Zimring says, that aggressive stop-and-frisk policies have been a part of policing in New York ever since the great modernizing reforms of 1994 and 1995. One reason that the NYPD and the Bloomberg administration are so adamant that it is impossible to statistically separate stop-and-frisk from the broader tactics of hot spot policing may be that the two policies have never been separate in operation. (Hot spot policing, and the targeted focus on destroying drug markets that came with it, have been, of course, profoundly successful — one of the great public safety efforts in American history.) Kelly seemed to hint at this on his Morning Joe appearance. “This is what you pay your police officers to do,” Kelly explained. “If they see something of a suspicious nature you want them to engage. Otherwise they become just totally reactive to 911 calls.” The commissioner continued: “Stop and question and sometimes frisking … is essential to what we’re doing.”

To believe that stop-and-frisk should end is not necessarily to believe that it should never have been tried: It seems as if the NYPD may have adopted a whole group of policies to deal with the incredibly complicated problem of crime, and then when that whole group worked, kept and defended each of the individual policies. Given the importance of what is at stake — lives, prosperity — that it is a sensible reaction. But the research, and the politics, have begun to tip, and one reasonable way to understand the contours of the current political debate over stop-and-frisk is to say that public is now asking for a more specific defense of the policy (how does it work, and where should New Yorkers look to see the effect) than Bloomberg and Kelly have been able to offer.

In the last few days, as the Mayor has been consumed with this debate, Bloomberg has vascillated between his best political instincts and his worst. There has been the exasperated, entitled pique: “Your safety and the safety of your kids is now in the hands of some woman who does not have the expertise to do it,” Bloomberg said of Judge Scheindlin on his radio address this weekend. (Some woman!) There have also been the sudden, unexpected gestures of humane feeling: “If I had a son who was stopped, I might feel differently about it,” the Mayor acknowledged to Ken Auletta, in this week’s New Yorker. But then Bloomberg has found himself in an ironic position for a famous technocrat: Defending a policy whose successes he has come to very much believe in, but whose effectiveness he cannot prove.