This cover story by Richard Reeves, titled “Jerry Ford and His Flying Circus: A Presidential Diary,” opens with a gaffe. Gerald Ford had been inaugurated three months earlier as Richard Nixon resigned and had within weeks pardoned his predecessor. The new president was well along toward establishing his reputation as an ill-spoken bumbler. As the story opens, he’s giving a speech at Mesa College, in Colorado, and mispronounces its name (“meesa”), then tries to recover with a lame joke. And, then, as Reeves writes:

So it went as President Ford traveled 16,685 miles campaigning for Republican candidates in the month before Election Day, 1974. It was a big story — Nightly News, Page One! — with airport announcers parodying The China Trip at every stop. But journalism has its limits. Journalism is covering something, even when there is nothing. There is no accepted technique that deals adequately with the president’s travels. Do you write:

Grand Junction, Colorado, Nov. 2 — President Ford had nothing to say and said it badly to a friendly and respectful but slightly stunned crowd of 5,000.

It is not a question of saying the emperor has no clothes — there is a question of whether there is an emperor.

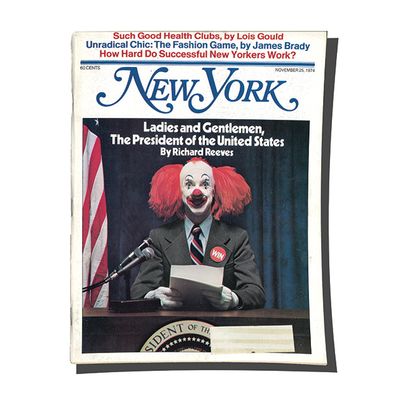

This was a relatively outré cover for its time, but New York — then only six years old — had established itself as a highly irreverent magazine that took pokes at the powerful, and especially at Nixon, when they’d earned it. Saturation coverage of the president was very different in the 1970s, Reeves explains today, and the press had a different role: “The boys on the bus are a long time ago. There were hundreds of us, and print was still dominant — television only became dominant during the Carter campaign, through Sam Donaldson. We totally controlled the agenda. Nobody questioned that the press controlled the agenda. Now the press doesn’t control anything.” He laughs. “They’ve outlasted us, the bastards!”

That said, he admits that this feature isn’t his proudest moment. “It’s not a story that should be immortalized.” At the time, he’s quick to add, “it’s exactly what I felt was happening. The man couldn’t pronounce a word — it was one blunder after another.” But, he continues, “years later, I wrote a book about him. And when I talked to him in that period, he said that, after he pardoned Nixon, he thought the government couldn’t function if Nixon was being dragged from courtroom to courtroom, both civil and criminal cases. I laughed at that at the time, and I think a lot of other people did. But what made me think he was probably right and I was probably wrong was the O.J. case. It was one of the first times you could see that an individual case could immobilize the country. I even wrote a piece for American Heritage — this was years later — apologizing to Ford for that part of it.” The headline was I’M SORRY, MR. PRESIDENT.

Part of his affection for Ford, of course, is relative. “Now I think we’re really in trouble. Gerald Ford was not a dangerous man. He was the nicest guy in the world — never should’ve been president, really, got there by accident. He wasn’t the most competent man in the world — there was a bit of Rick Perry about him, particularly on the thing about whether Poland was a communist country. But he was this outgoing, generous, maybe-not-always-knowledgeable human being, especially compared to this, Trump, who seems to be looking for revenge. He was at heart a good man, and I don’t think Trump is. I just watched him at some donors’ dinner. Same old shit.”

*This article appears in the January 23, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.