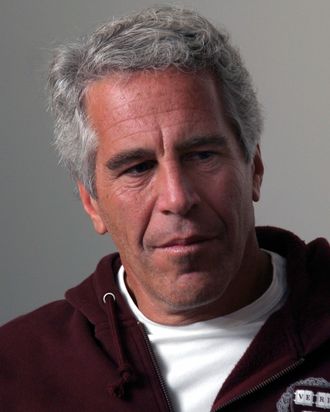

Ten years after a then-imprisoned Jeffrey Epstein was granted access to a work-release program in Palm Beach County, Florida — which he allegedly took advantage of to recommence sexually abusing young girls — Sheriff Ric Bradshaw’s office is discontinuing the program for everybody, the Miami Herald reports. The decision, announced on Monday, goes against the recommendation of a county commission that, despite the program’s shortcomings, deemed it worth preserving after a four-month investigation into its policies and procedures.

Work-release programs allow incarcerated people to leave confinement for a set amount of time in order to perform outside work shifts, after which they return to a correctional facility, a site designed specifically for work-release detainees, or to house arrest. Palm Beach County’s version was seldom used — just 52 times in the past five years — but supporters have praised it as an important means for keeping its participants connected to their regular lives, jobs, and old communities.

Research demonstrates the benefits of such efforts: People who completed work-release programs in Florida between 2004 and 2011 had lower rates of recidivism than their counterparts and were vastly more likely to find employment within the month after being released, according to a 2015 report by the Florida Department of Corrections and the Florida State University College of Criminology and Criminal Justice. The program run by Bradshaw’s office has been suspended since August, pending the commission’s investigation. As of Monday, its participants will be incorporated into the regular house-arrest program and permitted to work only if a judge okays it.

Palm Beach County mayor Dave Kerner has expressed his support for the original program and said he planned to continue it under county supervision, according to the South Florida Sun Sentinel — an encouraging sign that it could survive the sheriff’s abandonment after all. (The majority of Florida’s work-release programs are currently run by counties, not local sheriff’s offices.) But few are buying Bradshaw’s claim that he’s ending it because it wasn’t cost-efficient, though that was among the commission’s findings. “Cost may have been cited by [the sheriff’s office], but it’s clear the real issue stems from the bad PR and international scrutiny the agency received due to its improper and possibly criminally negligent oversight of Jeffrey Epstein,” state senator Lauren Book told the Herald.

Epstein’s alleged abuse of the program has been a subject of intense criticism. When he was granted access to it in 2009, the late financier hired a crew of sheriff’s deputies to be his bodyguards. He was transported to his foundation at a downtown high-rise up to six days a week and sometimes to his Palm Beach mansion, despite restrictions on home visits; at least two women have claimed that Epstein abused them during this time. But faced with this single case’s potential mishandling, the sheriff’s office’s decision to shutter the program seems to be motivated not as a reckoning with how its deputies might’ve enabled the billionaire who was paying them but by more routine American panic over being too lenient toward people convicted of crimes.

A release program that boasts a mere ten participants on average per year is a poor candidate for being called lenient in the first place. But the logic that fuels mass incarceration — and has, in the United States, helped produce the largest carceral system in the world — has little room for relativity or the nuances of individual circumstances in most cases. Jails and prisons are full of people who might otherwise be out on furlough, parole, or even walking free were it not for the kind of systemic risk aversion that sees a crime committed during work release and suspends a 42-year-old program rather than accepting that awful things happen and convicted people still deserve channels for reintegration. The Palm Beach County program’s participants were already being kept out of work pending the county commission’s investigation, which began in August. Now it seems they’re functionally being punished because of Epstein — who hanged himself in a Manhattan jail cell earlier this year — and must wait even longer for the county to “work out the details,” as Kerner put it, before the program even has a chance of starting up again.

To whatever degree discontinuing such an initiative due to its supposed risks can be attributed to some reasoned insight, it’s that elected officials — like sheriffs — tend to lose elections if they’re perceived as insufficiently harsh on people who break laws and get caught. The most widely cited example is the case of Willie Horton, who became an avatar for then–Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis’s perceived softness on crime after then–Vice-President George H.W. Bush blamed a statewide furlough program that Dukakis had supported for letting Horton leave prison for a weekend, when he raped a woman and assaulted her fiancé.

The success of Bush’s attack ads — he beat Dukakis in the general election and became president the following January — presaged the punitive politics of the decade that followed. The 1990s were defined by a bipartisan consensus that one chance equaled one too many for lawbreakers. Among the results were skyrocketing incarceration rates and an intensified push for policies that kept people locked up longer for lesser crimes, and narrowed their opportunities for self-education and self-improvement — like the 1994 Crime Bill’s elimination of Pell Grants for federal prisoners seeking to pursue higher education — while locked up.

If nothing else, the short reach and precariousness of a program that’s let a small handful of people lay the groundwork for a life beyond incarceration is an opportunity to consider why hope remains available to so few. Only five Florida counties offer work-release programs, according to USA Today. Prison and jail remain environments of sustained torture and civil death marked by routine violence, the deprivation of prisoners’ civil rights, and a lifetime of vastly diminished opportunity should they ever get released. Americans’ collective fear that more people might get hurt — or, God forbid, officials might not get reelected — if our government becomes anything less than the most aggressively carceral on Earth belies that prison and jail are as unlikely to deter crime as harsh punishment is to address its root causes. If anything, America needs more programs like the one shuttered on Monday in Florida, not fewer. Palm Beach County’s chance to implement a more generous and expansive vision begins now.