Another 1.1 million Americans filed for first-time unemployment benefits last week. The U.S. economy is no longer hemorrhaging jobs the way it did in April. But the bleeding is neither staunched nor steadily slowing. Thousands of small businesses have gone bankrupt in recent weeks. Waves of layoffs are rising up from the ground floor and washing away hoards of middle managers. Meanwhile, thanks to the GOP’s obstruction of COVID-19 relief, tens of millions of Americans just saw their monthly incomes slashed by $2,400, while cities and states throughout the country are preparing for mass firings of public workers. The macroeconomic consequences of these developments have yet to fully register. As is, more than 28 million Americans are at high risk of eviction before year’s end, according to a report released by the Aspen Institute earlier this month.

Oh — and the school and college re-openings we’ve witnessed thus far suggest that there is a high risk of COVID-19 cases rising sharply as autumn descends.

All of which is to say: If Joe Biden is fortunate enough to move into the Oval Office next January, he is all but certain to preside over a broken land.

At present, the U.S. economy is on a neo-feudal trajectory. Almost all recessions hit the poor harder than the rich. But the COVID-19 crisis has been exceptional in its inequity. The sectors most vulnerable to a pandemic-induced collapse in demand — such as restaurants and hotels — are also among those most heavily staffed by low-income workers. America’s tech giants, meanwhile, boast business models that are uniquely compatible with mass quarantine, and their white-collar workers have (mostly) remained gainfully employed. What’s more, thanks to the Federal Reserve’s robust support for asset prices, the net worth of American households may actually be at a record high. Put differently, Americans who owned homes and stocks before the pandemic — and maintained their employment throughout it — are collectively richer today than they’ve ever been, even as the number of U.S. children living in food-insecure households has skyrocketed.

In this context, restoring full employment (and some semblance of shared prosperity) will require a combination of massive fiscal stimulus and progressive redistribution. Biden has given some indications that he understands this. Before the pandemic, the Democratic nominee pledged to spend $1.7 trillion over a decade on a green jobs program; last month, he vowed to spend $2 trillion over four years on climate stimulus. The overall price tag on his economic program is roughly $3.5 trillion according to Bloomberg. And if Congress fails to pass another round of COVID-19 stimulus before next year, that figure would ostensibly be higher (presumably, Biden agrees with House Democrats that the federal government should provide states and cities with nearly $1 trillion in fiscal aid). Encouragingly, Biden’s apparent openness to a robust stimulus program is shared by some self-styled fiscal hawks in Nancy Pelosi’s caucus. In July, the chair of the centrist New Democrat Coalition, Derek Kilmer, told reporters that “getting bogged down in trying to identify offsets is not appropriate in an emergency.” The bulk of Kilmer’s moderate allies voted for the $3.4 trillion Heroes Act in May of this year.

And yet: Biden has a much-deserved reputation as a deficit hawk, as do some of his top aides. This week, one of the nominee’s top advisers suggested that Trump’s deficits will leave the next Democratic administration with little room for maneuver. As the Wall Street Journal reports:

Former Delaware Sen. Ted Kaufman, a Biden confidant who succeeded him in the Senate, predicted during a Wall Street Journal Newsmakers Live interview Tuesday that a large increase in federal spending would be difficult to achieve in 2021.

“When we get in, the pantry is going to be bare,” said Mr. Kaufman, who is leading Mr. Biden’s transition team. “When you see what Trump’s done to the deficit … forget about COVID-19, all the deficits that he built with the incredible tax cuts. So we’re going to be limited.”

Kaufman’s comments are concerning for multiple reasons.

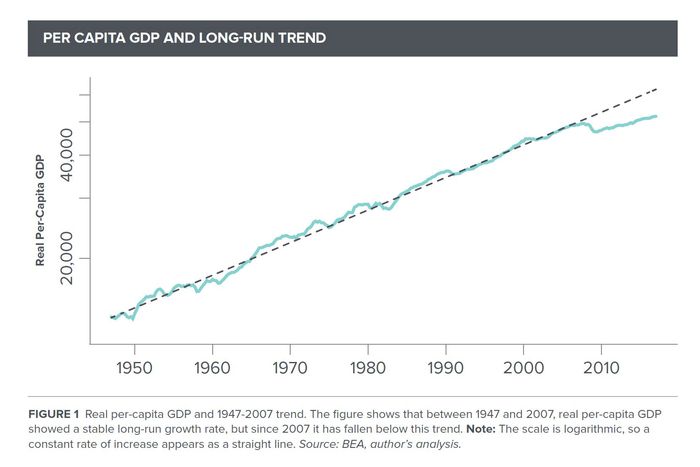

In 2009, a unified Democratic government declined to provide the economy with the level of stimulus necessary for spurring a rapid recovery in deference to deficit-phobia; specifically, the White House asked for less spending than its own economists believed to be warranted on the merits because it felt that a $1 trillion bill would be politically toxic. As a result, the post-2008 recovery was the slowest and weakest in modern U.S. history. That sluggish rebound had immense human costs as America’s most vulnerable workers — those with limited education, disabilities, or criminal records — were effectively locked out of the labor market for a decade. But the toll of inadequate stimulus was also macroeconomic: Since World War II, every time the U.S. economy entered a downturn, it eventually caught back up with its pre-recession growth trajectory — until 2009. By failing to rapidly re-match workers with jobs, policymakers durably reduced our economy’s productive capacity as discouraged Americans permanently left the labor force and capital fell out of use.

Of course, as we know now, the Democrats’ decision to prioritize national debt minimization above full employment did not actually curb the growth of the national debt. To the contrary, it simply gave Donald Trump and the Republican Party more fiscal space to fill with tax cuts and Pentagon budget increases.

Critically, this historic spending spree has not triggered any of the adverse economic consequences that deficit hawks would have predicted. As the federal deficit soared, inflation and interest rates remained extraordinarily low. America has little trouble finding buyers for its debt or maintaining price stability. And by supplying global investors with the safe assets they demand — in the form of U.S. debt securities — America’s fiscal profligacy has arguably helped stabilize the global financial system.

Alas, Kaufman is nevertheless citing Trump’s profligacy as a reason why the party must once again condemn America’s most vulnerable to years of poverty and involuntary unemployment. Separately, the fact that Kaufman emphasizes the Trump tax cuts as a constraint on fiscal space raises questions about the sincerity of Biden’s commitment to repealing the bulk of those tax cuts.

A charitable reader might conclude that Kaufman merely takes a pessimistic view of the politics of deficits and taxation. Which is to say: He believes that Biden will lack the Senate votes to repeal the Trump tax cuts and enact green stimulus. But the metaphor Kaufman deploys, a bare cupboard, suggests that he believes there is an objective constraint on the government’s spending power, not a political one.

And this interpretation is buttressed by the fact that Biden himself has voiced nearly identical sentiments. At the final debate of the Democratic primary, Biden suggested that Trump’s policies had exhausted the nation’s fiscal reserves, saying:

The problem is, the policies of this administration economically have — we’ve eaten a lot of our seed corn here. The ability for us to use levers that were available before have been used up by this godawful tax cut of $1.9 trillion … And so we’re going to have to just level with the American people.

Multiple Biden advisers recently told Vox’s Dylan Matthews that the candidate is a “deficit hawk at heart.”

An optimist won’t have that much trouble dismissing these grim portents. After all, most of the moderates in Nancy Pelosi’s caucus voted in May to supply Donald Trump with $3.4 trillion in election-year stimulus (after already supplying with the $2 trillion CARES Act relief package). Is the party really going to be less willing to stimulate the economy during a Democratic president’s honeymoon than it was amid a Republican president’s reelection campaign?

On the other hand, if Democrats do eke out a Senate majority, Chuck Schumer will need the support of some of the most conservative lawmakers in the party to pass legislation. If the Biden administration is ambivalent about its own fiscal agenda, it’s hard to see how it will allay the doubts of Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema, and their ilk. And if Biden’s promised green stimulus ends up amounting to nothing more than a campaign-website decoration, then America will “build back worse” for the second time this century.